Senate rejects House debt bill

WASHINGTON -- House GOP leaders won narrow approval of a plan to raise the federal debt limit Friday after revising the measure to appeal to rebellious conservatives, but the bill was quickly rejected in the Senate, where lawmakers were pursuing a separate, bipartisan agreement to avert a national default.

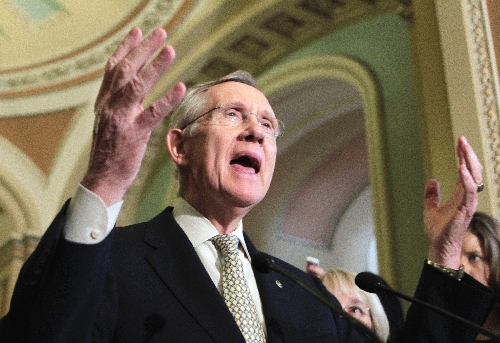

Heading into the final weekend before the Treasury expects to start running short of cash to pay the nation's bills, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., was poised to forge ahead with his own proposal to grant the Treasury additional borrowing authority.

The Senate set its test vote about 1 a.m. on Sunday, a middle-of-the-night roll call that underscored the limited time available to lawmakers.

Democrats conceded that they still lack the votes to repel a filibuster threat from GOP senators. But Reid beseeched his Republican counterpart, Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, to join him in reworking the Democratic measure so the Senate could pass it and send it back to the House before slumping financial markets open Monday morning.

"The last train is leaving the station, and this is a last chance to avert a default," Reid said in a speech on the Senate floor, arguing that the House bill would force Washington to endure another economy-rattling fistfight over the debt limit within a few short months.

"I say no, not again will we fight another battle like the one in which we are now engaged," Reid added. "But default is not an option, either. And we cannot wait for the House any longer. I ask my Republican friends, break away from this thing going on in the House of Representatives."

Among the House bill's flaws, Reid said, it would require Congress to revisit the contentious debt issue within months and not offer certainty to financial markets.

"A Band-Aid approach to a world crisis is an embarrassment to Congress, to this country and to the world," he said.

Sen. Dean Heller, R-Nev., voted for the bill and focused on its balanced-budget provisions in explaining why.

"The Senate had an opportunity to send a bill to the president that would put us on a path to balancing the budget," Heller said. "Any plan that goes to the president should create significant savings and make necessary structural changes for long-term fiscal stability."

Though several Republican senators said a bipartisan compromise presents the only logical way to break the weeks-long stalemate, McConnell's immediate response was not encouraging. In a statement, he praised the House for passing "its second bill in two weeks that would prevent a default and significantly cut Washington spending," and he criticized the Senate for "ginning up opposition."

In the Senate on Friday night, a frustrated Reid said his efforts to reach a compromise with Republicans were rebuffed. "The proposal I put forward is a compromise," Reid said. "We changed it even more today. We would have changed it more, but we had no one to negotiate with. The Republican leader would not negotiate with me."

Reid's revised bill would make it easier for President Barack Obama to raise the debt ceiling by $2.4 trillion. It would allow him to increase the limit in two steps as needed unless Congress passes resolutions of disapproval.

The idea had originated with McConnell several weeks ago, but Democrats said he was not a participant as it was added to Reid's proposal.

"This morning at 10 a.m., leader Reid asked Senator McConnell to come negotiate. The door was open all day. Nobody knocked, nobody walked in," said Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y.

Still, Senate Democrats said they had received "positive signals" from Republican leaders. And though there were no formal talks with McConnell, Democratic leadership aides said they were hopeful that Reid soon would unveil a measure that would win Republican support.

Before the House vote, Obama made a televised plea for compromise, arguing that the two parties are not "miles apart" and that he was prepared to work "all weekend long until we find a solution."

Both the House and Senate bills call for cutting deeply into agency budgets over the next decade and creating a new 12-member committee tasked with identifying trillions of dollars in additional cuts by the end of this year. Reid's bill would extend the $14.3 trillion debt limit into 2013, however, while the bill from House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, would give the Treasury a reprieve only until February or March. If the committee failed to come up with $1.8 trillion in savings, Boehner's bill would force another battle over whether to grant the Treasury additional borrowing power.

In brief White House remarks, Obama noted that the two sides are "in rough agreement" about the size of the first round of spending cuts and that "the next step" to rein in borrowing should be a debate over "tax reform and entitlement reform."

"If we need to put in place some kind of enforcement mechanism to hold us all accountable for making these reforms, I'll support that, too, if it's done in a smart and balanced way," Obama said.

Talks have been under way for weeks about how to structure a plan so that both parties are encouraged to engage seriously in negotiations over future debt reductions. One approach would be to require tax hikes and across-the-board spending cuts -- which would be unattractive to many lawmakers -- if the committee refuses to come up with recommendations for added savings.

On Friday, Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill., the second-ranking Democrat in the Senate, said the design of that mechanism "is what all the negotiations are about." He added, "That's going to be part of the endgame."

Without such an agreement, Obama warned that the United States stands to lose its sterling AAA credit rating -- "not because we didn't have the capacity to pay our bills. We do. But because we didn't have a triple-A political system to match our triple-A credit rating."

Obama again urged Americans to contact their representatives, clogging Capitol Hill switchboards for a second time this week. White House officials also tweeted several Twitter handles for Republican lawmakers so voters could press them to "get past this."

The president's lobbying campaign appeared to have little effect in the House, where attempts by Boehner to move toward the center were rebuffed. Earlier this week, Boehner unveiled a measure drafted largely by aides to Reid and McConnell, but he was forced to yank it from the floor late Thursday, when his right wing refused to fall in line.

For the next 23 hours, neither Boehner nor any other Republican leader issued a formal statement or paused in the Capitol hallways to explain to reporters what had happened.

Then on Friday, Boehner rewrote the bill to prevent an increase in the $14.3 trillion debt limit unless both chambers of Congress approve an amendment to the Constitution to mandate a balanced budget. The change swayed a handful of holdouts, and the measure passed 218-210, with every Democrat and more than 20 Republicans voting no.

Even some Senate Republicans were perplexed by the disarray in the House.

Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., repeated his criticism of the balanced-budget amendment as "bizarro." And Sen. Roy Blunt, R-Mo., who served under Boehner in House leadership until his election to the Senate last year, said the rewritten House bill "may be more of a repeat" of the failed "cut, cap, balance" approach championed by conservatives "instead of a movement to being part of the solution."

As they had announced previously, Republican Rep. Joe Heck voted for the bill, and Democratic Rep. Shelley Berkley voted against it.

Berkley said the bill "is a short-term deal that would wreak havoc on our economy" by allowing the government's borrowing to be increased by a relatively small $900 billion while forcing Congress to revisit the issue next year.

Heck said the bill contained "real savings" to offset the additional government borrowing and did not raise taxes. He said he also favored provisions that would require Congress to pass a constitutional amendment to balance the budget before the debt ceiling could be fully raised to the levels requested by Obama.

Stephens Washington Bureau Chief Steve Tetreault contributed to this report.

MARKET REACTION

Stocks: The Dow Jones industrial average had a sixth straight day of losses. On Friday, it closed down 97 points at 12,143. The S&P 500 index had its worst week in a year.

Bond insurance: The cost to protect against a U.S. default within one year has reached a record high this week.

Gold: Gold rose just under 1 percent to settle at $1,631 an ounce Friday. When gold prices are high, experts say it’s a good indicator that people are scared to invest in other markets.

Currencies: An index measuring the dollar against six other currencies fell 0.6 percent.