American taxpayers own a stake in this Nevada lithium mine. Will it pay off?

RENO — The museum inside the University of Nevada, Reno’s Mackay School of Mines is a living scrapbook of the mining industry that gave the Silver State its name.

Three floors and rows of glass cases feature small, colorful samples of ore from mines of yesteryear. The basement’s opulent, rotating silver collection — complete with candelabras and silverware — belonged to the school’s namesake, John Mackay. He was a beneficiary of the 1850s discovery of silver and gold near Virginia City, known as the Comstock Lode, which led to Nevada’s statehood during the Civil War.

But there’s one glaring omission from the museum’s cases — a mineral that’s breathing new life into the industry: lithium. Called “white gold” by some, lithium has sparked what many say is a modern Gold Rush — one Nevada leaders hope to keep in Nevada, said Fred Steinmann, a principal investigator for UNR’s Tech Hub focused on making that goal a reality.

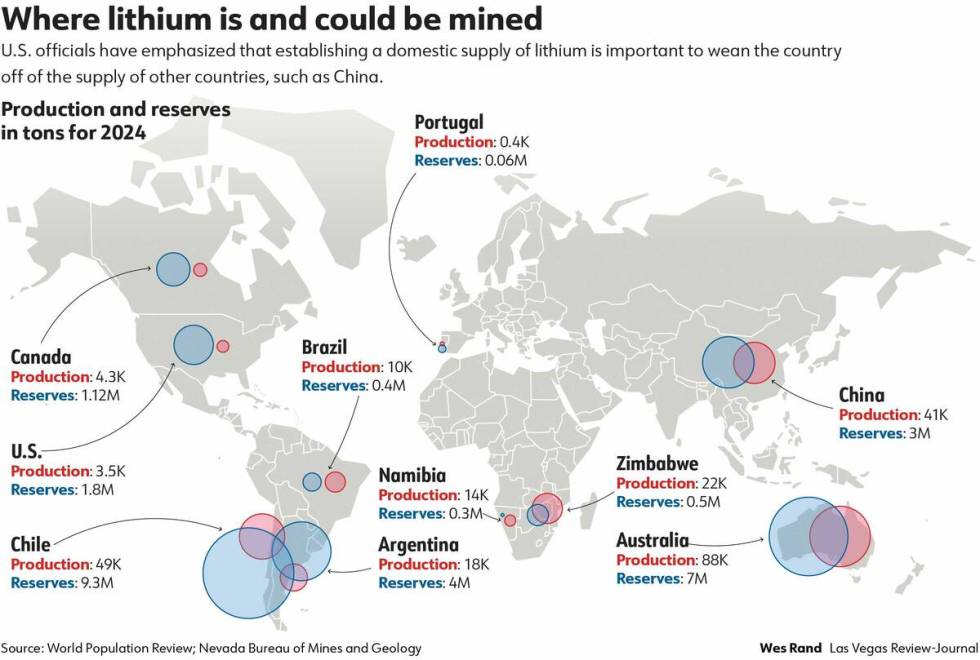

“We are, to a degree, hilariously dependent on foreign nations to provide critical elements needed to ensure national security,” Steinmann said. “We are at risk from simply just being cut off from those supplies, unless we build the domestic capability here.”

That’s what UNR is doing with Steinmann’s hub — working to bring every step of lithium battery production onto Nevada soil, and boosting rural economies along the way. It’s propped up by a $21 million federal grant from the U.S. Economic Development Administration, and disbursed its first bit of funding to Great Basin College in Winnemucca for an Industrial Tech Center in October.

The second of three fully permitted lithium mines in Nevada, the Thacker Pass mine in Humboldt County fits well into this bipartisan story of independence from China. The country, which has weaker environmental laws and limited safety regulations, dominates as the primary miner or refiner of more than half the minerals that the U.S. Geological Survey considers to be critical.

Only one U.S. lithium mine is operational, however: Silver Peak, in Nevada’s sparsely populated Esmeralda County halfway between Las Vegas and Reno.

“Lithium in Nevada is certainly one of the new bright spots of the economy,” said Rep. Mark Amodei, Nevada’s sole Republican leader in Congress, in an interview. “Each project sinks or swims on its own merit.”

Five phases on the table

Despite opposition from hundreds of Indigenous people in the Great Basin, a formal legal challenge attempting to protect a heritage site and the water table, and a cease-and-desist order from the Nevada state engineer, Thacker Pass has persisted.

What started off as two phases that would mine a 2.3-mile-long, 370-foot-deep pit on the north side of state Route 293 has turned into the ambition of five phases. That would prolong the project from 41 years to 85 years, pending permits — ones that become easier to get once a mine gets going.

Company spokesman Tim Crowley, who declined an interview for this series, abruptly canceled the Las Vegas Review-Journal’s pre-planned, on-the-record tour of the Thacker Pass construction site days before it was set to take place in July.

Only after an in-person interview led Winnemucca Mayor Rich Stone to ask the company to give the news organization a tour of the site did executives agree to a tour of its workforce housing and the mine site, with the understanding that no employees or representatives could be interviewed.

The company demanded editorial control over photography, but the Review-Journal elected not to take photos because such a demand is against its standards. Later, within minutes of putting a drone in the air adjacent to the mine on public land, a private security guard approached a Review-Journal photographer to remind him that drones could not be flown above the site.

In July, the construction site was just that — a site under construction. But the footprint of the project will be incredible. By the fifth phase, should the company get more permits, the single-lane state highway heading out to the mine will need to be rerouted so the pit can extend to what’s currently the south side of the road.

The mine manager pointed out mounds of dirt and vegetation that will stick around for decades for a reclamation plan that would try to restore the landscape to its former state on an undetermined date.

An economic promise — at a cost

Stone, who has served in Winnemucca city government for more than two decades, said he’s well aware that the Thacker Pass mine could take away his home’s small-town charm.

Winnemucca, the seat of Humboldt County about 165 miles northeast of Reno, offers amenities like hotels, restaurants and grocery stores that don’t exist elsewhere in the county.

“A community has got to grow to get better,” Stone said, adding that many of his constituents wouldn’t mind chains like Olive Garden or Home Depot coming to town.

U.S. Highway 95 is the main byway for the county on the way to Oregon heading north. The small ranching hub of Orovada is the closest community to the Thacker Pass mine, and the former mercury mining town of McDermitt is due north by the border.

Closed-door negotiations with ranchers in Orovada has resulted in some success, particularly in Lithium America’s agreement to stay off a less-kept-up local road and the relocation of the Orovada School away from the highway.

The Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe has secured a community benefit agreement with the company, though Crowley and the tribal chair declined to provide specifics as a dialogue between the two parties continued.

Lithium Americas has chosen Winnemucca as the gateway to its mine, transporting huge trailers that will effectively serve as dorm rooms for nearly 2,000 temporary workers at the height of construction.

Politicians who represent Humboldt County on both sides of the aisle have toured the housing construction and have shown support. They include Amodei and Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo, as well as U.S. Sens. Catherine Cortez Masto and Jacky Rosen, both D-Nev.

Today, in addition to beat-up trucks and tourists making the long haul to Oregon, big white buses frequently run up and down the highway to the mine in Orovada, passing by lush green fields and cattle.

Winnemucca braces for growth

Winnemucca may be the closest to an urban hub for Humboldt County, but it hasn’t experienced any significant growth in the last decade. It was home to about 8,390 people as of 2023, according to U.S. Census data.

Short-term living arrangements for mining contractors away from their spouses generally have a bad rap, sometimes called “man camps” because of high incidents of crimes like sexual assault, particularly involving Indigenous women. In 2017, the U.S. State Department linked the presence of extractive industries like mining and oil in small communities to increased sex trafficking.

“Law enforcement has some concern bringing in thousands of contractor construction workers who are temporary,” Stone said. “We’ve worked well with Lithium Americas and with Bechtel, which is doing the construction. If we have issues, we will work with them. If they have employees who keep getting out of hand, they will lose their job.”

Those who work for Sawtooth Mining, the long-term mine operators, instead are building lives in Winnemucca, buying houses and moving their families there full time.

In response to concerns about safety, Crowley said building the housing facility was a safety measure in itself. All employees and contractors must abide by the company’s code of conduct, he said, which emphasizes “collaborative and trusting relationships” with surrounding communities.

“The safety of our employees, including contract construction workers, and the community is paramount,” Crowley said.

Liquid sulfur to be trucked in

Depending on whom you ask, the impact the mine will have on the environment is either devastating or negligible.

Glenn Miller, now-retired chair of UNR’s Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Science, left the board of the environmental advocacy group he founded, Great Basin Resource Watch, over its protest of Thacker Pass.

Miller, who stood alongside the Western Shoshone in their protest of a gold mine at the heritage site of Mt. Tenabo, said he finds the mining process at Thacker Pass to be environmentally sound. And climate change is too large a threat to let legal challenges delay the mining of lithium and production of electric vehicle batteries, he said.

“There’s always an issue with any kind of mining, but this one is probably the most benign mine of its type I’ve seen in the 40 years I’ve been involved in mining,” Miller said.

In the other camp, John Hadder, the longtime executive director of Great Basin Resource Watch, has repeatedly decried the project, initially getting involved when community questions were going ignored during outreach from the Bureau of Land Management and Lithium Americas.

“The environmental analysis was poor. If you’re not doing the analysis right, we’re going to call you on it,” Hadder said. “We don’t want to see our environmental and social justice standards dropped or relaxed. That is a dangerous path.”

What happened at Thacker Pass is a harbinger for some of those societal value changes, Hadder said. And affected community members have had their concerns trampled over, in his view.

“That’s an important consideration across the board: Are we a society that wants to be more justice based?” Hadder said. “Would you want to live next to that mining project? That’s a piece of it that is getting lost: the voices of the people who are directly affected, and who are really going to be shouldering the consequences of this transition.”

Return on investment?

While Nevada appears to be in the lithium game for the long haul, the tone has shifted greatly under a new presidential regime.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk is no longer an ally of the White House or President Donald Trump, and the so-called “big beautiful bill” determining Congress’ spending has put EV tax credits on the chopping block. The $7,500 tax breaks for new EV owners are no longer available, leading some to question whether it will make the emerging lithium market go bust.

When asked about the tax credits, Amodei, the only Nevada representative who voted for the bill, said the lithium economy should move “full steam ahead in a responsible way” — despite policy changes.

Trump officials’ action on Nevada’s lithium economy have been a mixed bag. In an unusual move, the administration threw public support behind Lithium Americas by buying a 5 percent stake in both the company and the Thacker Pass mine.

However, later this year, as part of federal spending cuts, it pulled a $57 million grant from a lithium company angling for a lithium project near Tonopah.

While the price of battery-grade lithium in North America peaked in early 2023 at about $70,000 per ton, it has sharply dropped, hovering this year around $10,000 per ton, according to data provided by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a private company that offers up-to-date market data on critical minerals.

“If you discover a lithium deposit tomorrow, it’s probably going to take you 10 years to actually put it into production,” said Simon Jowitt, director of the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology and state geologist. “We don’t know what’s going to happen in two weeks’ time, never mind in 10 years. It’s very difficult to start to engineer and plan based on the volatility that’s happening right now.”

The fate of different sectors of the mining industry is inherently tied to market demands, perhaps best told in looking at a map of Nevada, where dozens of deserted boomtowns that went bust dot the desert.

It’s not just lithium that the public should be paying attention to, as gold, copper and even vanadium promise economic security throughout the state. Nevada is vastly under-explored for minerals, Jowitt said.

Lithium is likely to endure short-term market challenges as Nevada “plays the long game” in establishing a sector, he said.

This series was made possible, in part, by a grant and fellowship from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.