Inside the little-known protest lawsuit from a powerful lithium mining company

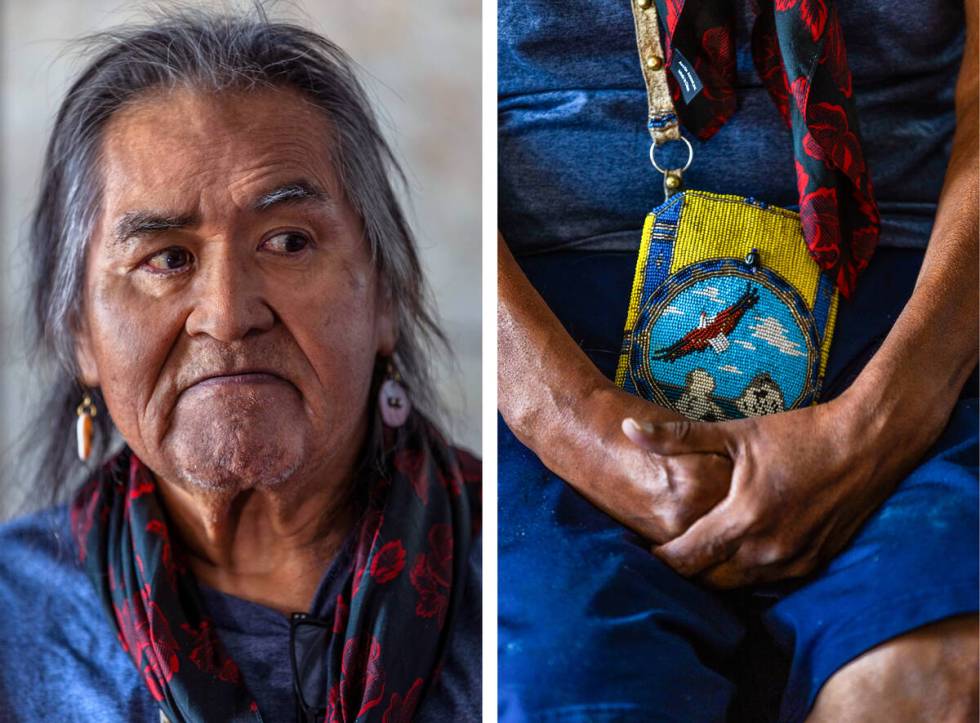

RENO — Inside Dean Barlese’s home on the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe reservation is a whiteboard with the numbers of tribal members who would drop everything to come to the beloved elder’s aid if needed.

So are the crinkled lawsuit papers the 68-year-old was served by Lithium Americas, a Canadian company building a lithium mine of immense size near sites his people consider sacred. The company is doing so with a boost from the Biden Administration, having closed on a $2.26 billion loan from the Department of Energy last year to help fund construction.

“It’s just a waste of ink and paper,” Barlese said, on one of the days he was free from dialysis and accepting visitors. “Any time we see these sacred sites off the reservation that are coming into jeopardy, we have to stand up.”

Americans now own a 5 percent stake in both the company and the mine — a deal eked out with Trump administration officials this year, signaling to some a vote of confidence from the federal government.

Barlese, who uses a wheelchair after losing one of his legs, is one of seven people who faced civil charges and potentially life-changing fines for participating in a 2021 protest when regulators had approved the Thacker Pass lithium mine in Humboldt County without what many felt was meaningful consultation with Native American tribes.

Scholars believe the Northern Paiute have lived in the Great Basin region for at least 11,000 years.

The lawsuit, which since has been settled, was a looming threat for the self-labeled “Thacker Pass Seven,” the group of defendants who called the mining company’s effort a SLAPP lawsuit, or a strategic lawsuit against public participation meant to intimidate critics. To some, it’s a clear power play to assert dominance and silence dissent.

Lithium Americas denies that it should be labeled a SLAPP lawsuit. Company spokesman Tim Crowley pointed to a court order in which U.S. District Judge Michael Montero ruled that Nevada’s anti-SLAPP laws did not apply.

“Here, the Court declines to open the floodgates to an influx of motions disguising unlawful activity as protected speech,” Montero wrote in a December 2023 order.

PeeHee Mu’Huh, or Rotten Moon

The charges that the seven had faced included civil conspiracy, nuisance, trespassing, interference with contractual relations, interference with prospective economic advantage and unjust enrichment.

“I find irony in it, trespassing,” said BC Zahn-Nahtzu, a Western Shoshone defendant who raises her children on the Hungry Valley reservation belonging to the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony. “Trespassing on my ancestral homeland.”

Defendants Dorece and Bethany Sam didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story. Dorece Sam has since cut ties with the other six and hired her own lawyer. The lawyer filed a separate motion to dismiss, which was denied.

Some Northern Paiute tribal members say the area near the mine is the site of an 1865 massacre, earning it the name of Peehee Mu’huh, or Rotten Moon in Paiute. The canyon by Sentinel Rock, the highest point in the area, lines up into the shape of a moon at certain angles.

The claim that the open-pit mine site itself is where the massacre occurred was contested in a separate court case that tribes lost. A federal judge determined that construction could proceed and that she was unconvinced there was sufficient proof that the massacre occurred at the mine site.

Max Wilbert and Will Falk, environmentalists who co-founded the Protect Thacker Pass group, had been camping at the proposed mine site since the mine was approved in January 2021, far before others joined them. In May 2023, it became the “Ox Sam Camp,” a Native-led prayer camp and protest named after one of the only known survivors of the massacre.

Because the federal government wasn’t going to, protesters said the goal was to physically delay construction with the camp.

Crowley, of Lithium Americas, called Wilbert and Falk “a minority voice and brazenly aggressive” in a statement, after declining an interview for this series. He called attention to their affiliation with a group called Deep Green Resistance and said the group holds “positions that conflict with tangible solutions to carbon reduction like electrifying our economy, which also brings economic development to rural areas like Humboldt County.”

It took Wilbert and Falk dozens of calls to find a defense lawyer who would take the case, largely because lithium mining enjoyed wide support from environmentalists who valued its role in the energy transition, they said. The activists were being iced out by their own community.

“It kind of felt like half the environmental movement was against us,” Falk said, adding that many are hesitant to take cases against the mining industry. “It was sort of a perfect storm of things that made it hard for us to find representation.”

Massey Mayo, the Winnemucca lawyer who represented most of the defendants, did not respond to multiple requests to comment on behalf of her clients.

Prayer camp allegedly gets rowdy

Sworn mine employee statements to police and a judge tell a story about the 2023 prayer camp and alleged trespassing that differs from interviews with the defendants.

Four construction workers wrote statements to the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office on June 5, 2023, that were obtained by the Las Vegas Review-Journal through a records request. Some detailed how protesters temporarily blocked the paths of heavy machinery, with complaints about drones and cameras peppered throughout the documents.

One heavy equipment operator, Bill Monson, wrote that protesters were beating a drum, yelling words he couldn’t understand.

“They did not threaten us, although it was a little exciting,” Monson wrote in his statement.

The Sheriff’s Office declined to arrest or cite anyone, advising the company to seek a court order, according to a court filing.

In a nearly 300-page court document asking that the defendants be trespassed from the mine construction site, five Lithium Americas contractors detailed their negative experiences with the protesters. A judge granted the request, remarking that letting protesters continue would cause “irreparable harm,” worsening relations with contractors, forcing employees to lose wages and putting their safety at risk.

The statements raised safety issues and said one of the camp’s teepees was delaying construction of a water line.

A May 15 security disturbance log showed 13 separate days when the company experienced delays or hang-ups as a result of protester activity. Another attached chart showed almost $380,000 in extra costs due to protests, not including legal fees.

“I am seriously concerned about my safety and well-being,” construction manager Josef Bilant wrote in a court declaration.

Environmentalist Paul Cienfuegos said in an interview that the statements were riddled with lies. The protest was peaceful, he didn’t witness some of the interactions described, and Indigenous people had a right to be there, he added.

“Nobody was there. Nobody ever approached us,” Cienfuegos said.

A ‘climate necessity defense’?

What’s unique about what would have been the defense strategy is that it could have treaded some new — and, perhaps, shaky — ground.

Wilbert said the case would have been a test of the “climate necessity” defense, an argument used by climate activists that claims it’s necessary to break some laws to prevent the climate crisis.

This case would have taken it a step further, Wilbert said, by putting forth a “biodiversity necessity defense,” meaning that defendants say trying to stop the lithium mine by breaking the law was an attempt to halt a project that contributes to the extinction of species.

The Sixth Extinction, as scholars call it, refers to the loss of species due to climate change — the first extinction event in Earth’s history that a consensus of scientists say is human-driven.

“One of the main reasons why we were out there taking action against this project was because the main driver of the biodiversity crisis is habitat destruction,” Wilbert said. “In Thacker Pass, the mechanism is mining. We’re arguing that, ‘OK, the actions that we took may have been illegal, according to the laws that are on the books, but we were taking action to try and get in the way of this broader mass extinction event.’”

In a June interview, Cienfuegos wasn’t optimistic about the defendants’ chances if the case headed to trial. His gut instinct was that they would lose, but was then hopeful for a settlement.

“A company that’s claiming to be doing something in support of a green energy future does not want to be pilloried nationally in the national media,” he said.

Neither the defendants nor Lithium Americas agreed to divulge the details of the confidential settlement. According to a docket provided by the Humboldt County clerk’s office, the case was closed in late October.

Difficulty persists for land defenders

Zahn-Nahtzu, the Western Shoshone defendant from the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, had to call tribal police when process servers took it upon themselves to enter the reservation and serve her the lawsuit — a violation of tribal law, she said.

The tribal member is a living encylopedia of the plants her ancestors needed to brave the Nevada desert, today using them for her brand of perfumes and skin care, Desert Hummingbird Designs. Her name means hummingbird in the Shoshone language.

On a visit to her home in July, she spoke with sadness about plants that could be lost from the McDermitt Caldera region as a result of mining. Zahn-Nahtzu is quick to point out how the state’s landscapes have changed post-colonization, becoming more flammable and riddled with invasive plants.

She said her people refer to plants and animals as relatives, always having a dialogue with them and a mutual respect.

“One of the challenges with Nevada is I’m always trying to insist that it is a beautiful place,” she said. “There’s not ‘nothing here.’ It is not a wasteland.”

In 2016, Zahn-Nahtzu felt called to the Standing Rock protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline that led to some arrests. She was called again to the Thacker Pass prayer camp, especially because her Western Shoshone ancestors are native to parts of the Great Basin.

It was Zahn-Nahtzu’s active Facebook presence that led her to be implicated in Lithium Americas’ lawsuit. The photo album from those few days are still in a public album intentionally, she said.

“They didn’t want us to speak out about the harms that they’re doing to not only the land, the plants, the animals, but our culture — the harms that they’re doing to us as a people,” Zahn-Nahtzu said. “The whole point was to make us be quiet.”

As a term of the settlement, none of the protestors can interfere with construction, enter the project area or fly anything in the airspace above the mine, according to the terms outlined in November court orders.

It explicitly does not prevent Zahn-Nahtzu or the other four Indigenous defendants from traveling to Sentinel Rock for worship, prayer or ceremony.

This series was made possible, in part, by a grant and fellowship from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.