Tribal members in Death Valley celebrate landmark law’s 25th anniversary

INDIAN VILLAGE, Calif. — Rising from his seat in the Furnace Creek auditorium, former Death Valley National Park Superintendent J.T. Reynolds interrupted a panel to go hug his old friend, tribal elder Pauline Esteves.

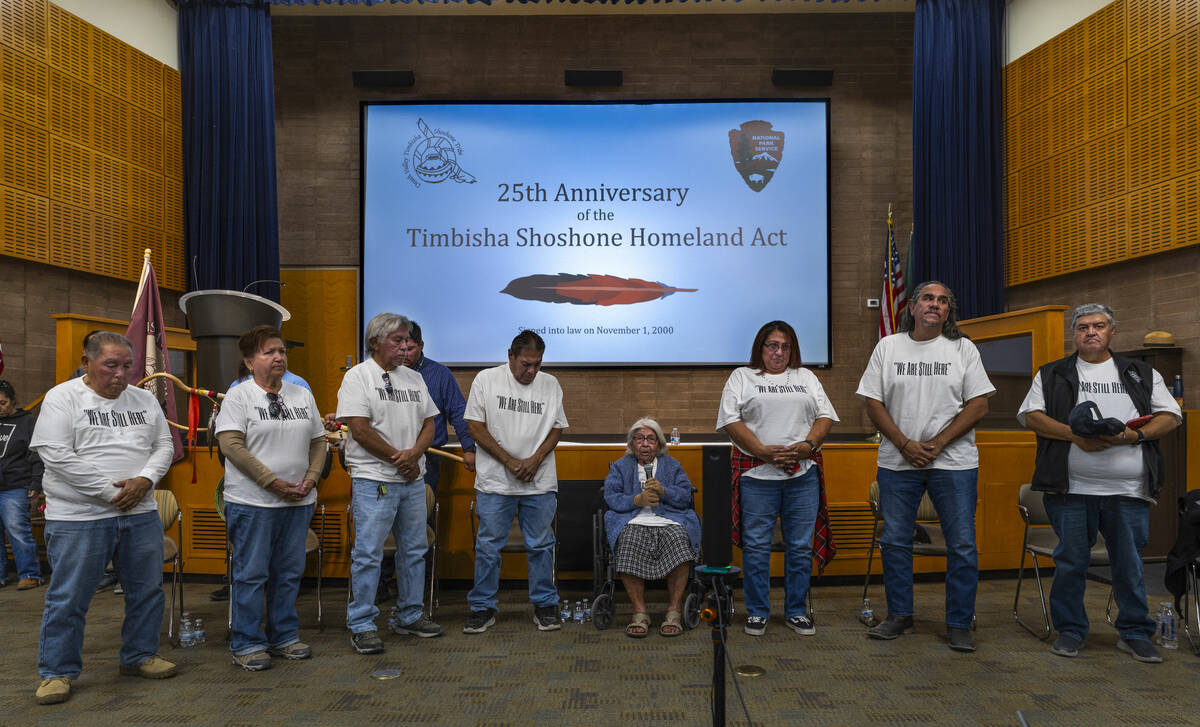

At 101, Esteves has seen the Timbisha Shoshone tribe’s relationship with the National Park Service evolve from hostile to celebratory. Esteves didn’t recognize Reynolds at first, but her eyes widened as he got closer.

“You wanna dance?” she quipped from her wheelchair, stirring laughter from the crowd of about 100 people.

The interaction harks back to a time when Esteves and other elders lobbied Congress to officially establish a reservation within Death Valley National Park. Years of pressure and advocacy paid off.

Signed in November 2000 by President Bill Clinton, the law gave 7,800 acres of land back to the Timbisha Shoshone — the only time in American history when the federal government returned land in a national park to Native American control.

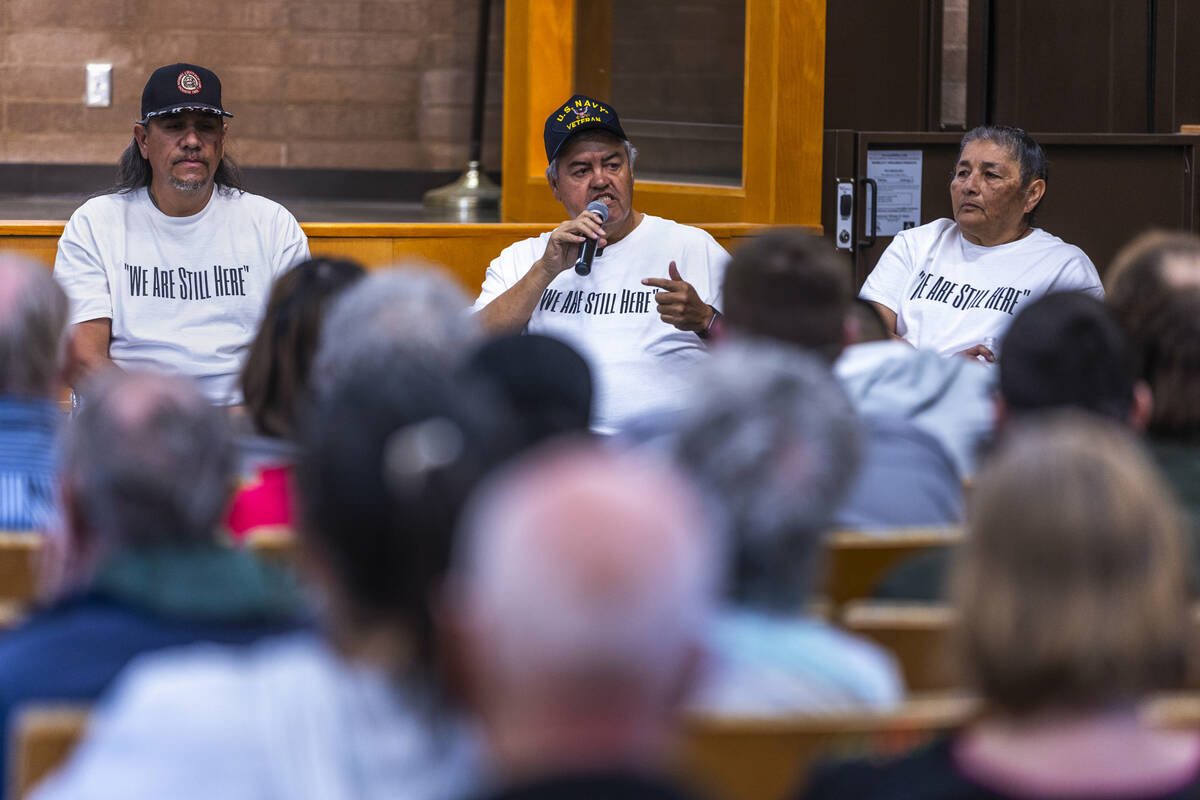

Dozens of tribal members and community members marched from the tribal offices to the Furnace Creek Visitor Center Friday morning in celebration of 25 years since the law’s passage.

The event comes a day after news broke that the National Park Service, at the direction of Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, was reviewing the park’s signage to “tell the full and accurate story of American history, including subjects that were minimized or omitted under the last administration.”

Reynolds, who served as superintendent from 2001 to 2009, oversaw the park service’s relationship with the tribe immediately following the signing of the law. He encouraged park leadership to let Indigenous knowledge lead policy, ensuring that the Timbisha Shoshone are consulted first before the agency acts.

“I wanted to make sure that Pauline knew her buddy Reynolds came here to represent,” Reynolds said.

A painful history

The park service-sanctioned panel largely stayed away from the subject of the signage review, which was spurred by an executive order titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.”

It has led to several changes in signage across the country, including the high-profile removal of a slavery exhibit in Philadelphia.

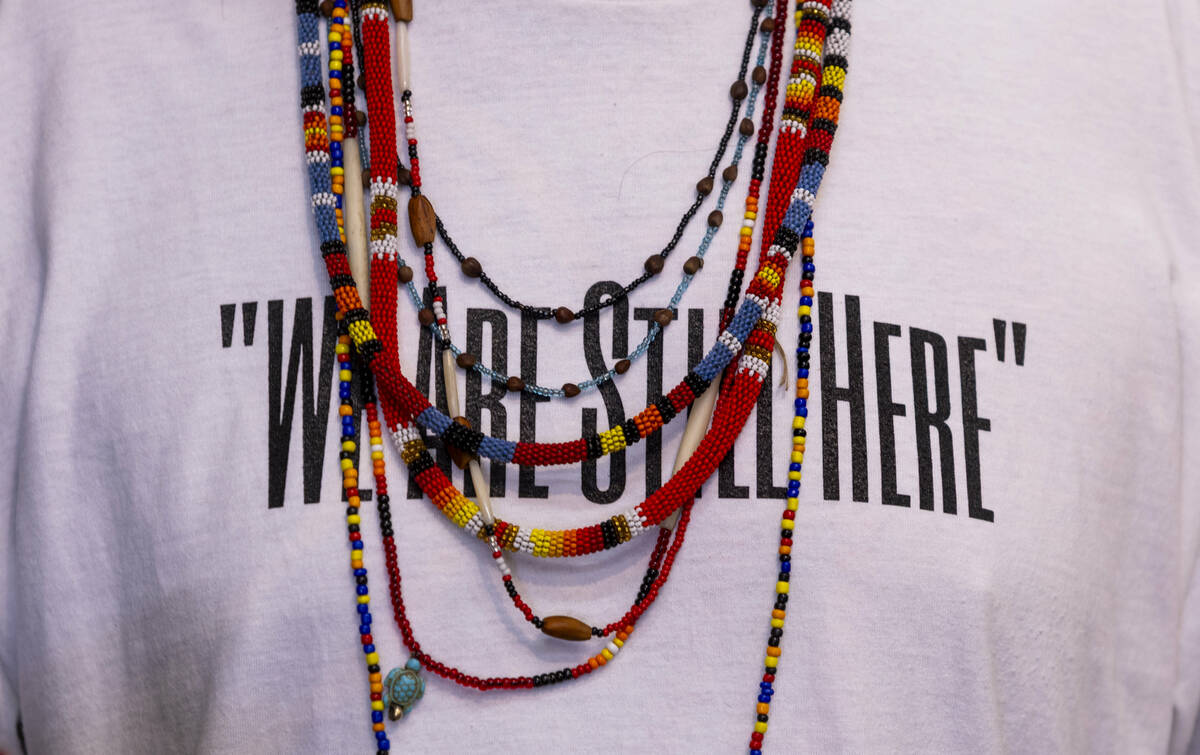

During the march, tribal members carried signs about the need to remember Native American history, including one that said: “History is not there for you to like or dislike. It’s there for you to learn.”

When Death Valley became a national monument in 1933, it did not include a plan for the Timbisha Shoshone. After the park service unsuccessfully tried to force relocation, the agency agreed to establish the Indian Village near Furnace Creek.

According to accounts from tribal elders, in the 1950s and largely up until the year 2000, when the law required that land be put aside for the tribe, the park service systemically targeted the tribe through policies, such as allowing rangers to destroy adobe homes and threatening eviction if tribal members didn’t pay rent.

Mike Reynolds, the park’s current superintendent, affirmed in his remarks that his staff is committed to working with the tribe on addressing any concerns they may have about sites of historical or religious significance.

“While the relationship has blossomed and grown in recent years, trust, friendship and true, heartfelt partnership do not happen overnight,” Mike Reynolds said. “It takes effort from each and every one of us to not be afraid to think of things differently and be open-minded.”

Is Interior ‘erasing history’?

Still, a few hundred feet away from Friday’s celebration, it remains unclear how the Trump administration may be altering the tribe’s historical narrative.

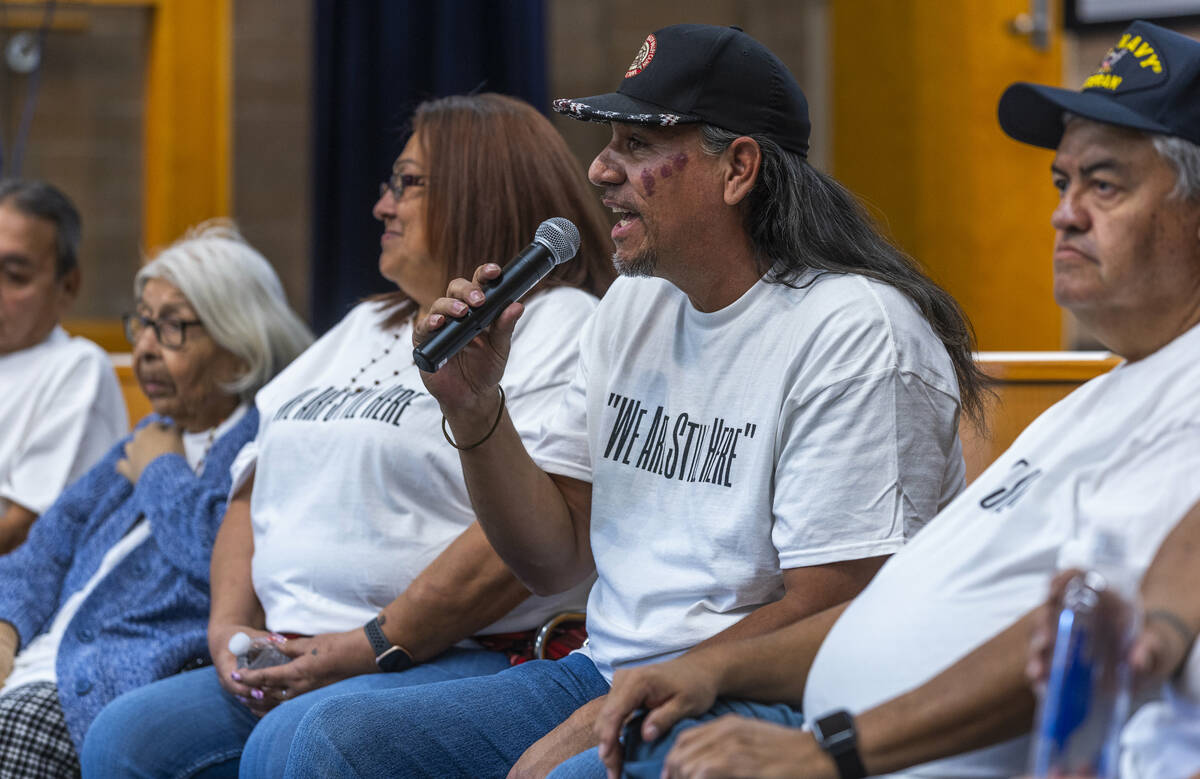

Jimmy-John Thompson, a tribal council member, said he takes seriously the legacy of persistence that elders have left behind.

He said the tribe has been working toward a so-called “co-management agreement” that would allow it to have more say in park decisions. That would promote better conversations, Thompson said.

“It doesn’t happen with an executive order and a Sharpie,” Thompson said.

In a statement from the Interior Department, officials wrote that the review of signage is being mischaracterized in the press.

The review “includes fully addressing slavery, the treatment of Native Americans, and other foundational chapters of our history, informed by current scholarship and expert review, not through a narrow ideological lens,” the agency said.

“Some materials may be edited or replaced to provide broader context, others may remain unchanged,” officials added. “Claims that parks are erasing history or removing signs wholesale are inaccurate.”

Timbisha Shoshone press on

Behind the joy of Friday’s celebration was a deep reverence for the tribal members who came before.

Tribal Secretary-Treasurer George Gholson said he doesn’t take the reservation lands he enjoys today for granted.

The 2000 law included language allowing the tribe to create its own cultural center, which is something the tribe will soon fundraise for, tribal officials said. The tribe is taking steps to remain a permanent part of its homeland’s story.

“We no longer have to be invisible,” Gholson said. “And it was through the negotiation, the fighting and the activism of the tribal elders and other people that are elders now or that are dead that made that happen.”

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.