In 50 years, DRI reaches worldwide

RENO -- A half century ago, a two-page bill passed by the Legislature planted a seed of knowledge in the Nevada desert that over the decades has grown tentacles of discovery around the globe.

The measure, signed into law by then Gov. Grant Sawyer on March 23, 1959, authorized establishment of the Desert Research Institute at the University of Nevada, Reno.

From the beginning its goals were lofty: "To foster and to conduct fundamental scientific, economic, social or educational investigations" and "encourage and foster a desire for research on the part of students and faculty."

Nevada's population was fewer than 300,000 then and the state was known more for gambling and quickie divorces than scientific research.

"I think it says quite a bit about the Legislature and the governor at the time," said Stephen Wells, president of the institute now called DRI.

"These people had a vision," Wells said.

Wells said the institute wasn't alone in its venture. At a time when the space race was on and atomic testing was under way, many research institutes were created in the United States.

"There was no guarantee that it would ever be successful," he said.

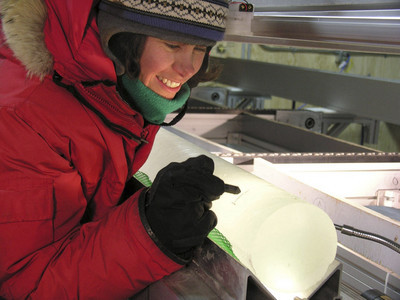

Fifty years later DRI can look back and point to the role it played in discoveries and applications around the world, from early efforts to monitor groundwater in the Great Basin to using sensors in space to find scarce water in Africa. Researchers from the institute made breakthroughs in tracking the origin, disbursement and distant effects of air pollutants and today are plotting global climate changes by studying ice cores at the poles.

Desert Research Institute first operated out of various buildings on the UNR campus. In 1962, it opened a Las Vegas location in a converted restaurant, and later moved to a renovated duplex.

In its first year it brought in about $2.5 million in research support. Today, that figure is $40 million from grants and contracts.

From the beginning, the institute's operating model was unique. As an autonomous facility, researchers would not be afforded tenure, as are veteran university faculty members. Instead, they were to find their own project funding.

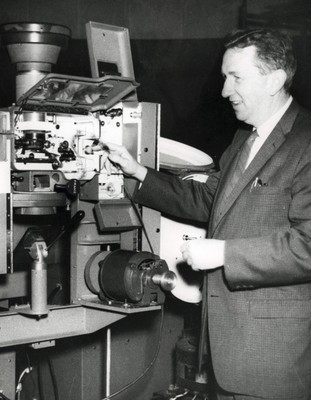

It was a liberating concept by the institute's first director, atmospheric physicist Wendell Mordy, said Joy Leland, one of the first employees hired at the institute in 1961.

"It was a very unusual situation for academia, and I think it all made us feel sort of independent, doing our own thing," she said.

That independence has attracted scientists from around the world, Wells said.

Today, DRI has campuses on both ends of the state, as well as satellite or shared facilities in Boulder City, Incline Village at Lake Tahoe and Steamboat Springs, Colo., where scientists study storm and cloud physics from within the clouds at a high elevation laboratory.

The institute employs about 500 people and at any given time has some 300 research projects under way in all corners of the globe.

Its growth is evidenced by DRI's annual award, the Nevada Medal, a coveted honor in the scientific community.