Gangsta Godfather

He squints into the distance and spits out his words like they were coated in something foul tasting, his steady glare just as hard on the eyes as the sun that beats down from above.

It's a bit past noon, and Morey Alexander's getting as hot as the asphalt cooking beneath his feet, his face a shopworn mask of indignation, his anger an immovable object, a boulder.

He's dressed like a villain from some old cowboy flick, clad in black from his sneakers to the rumpled ball cap squished down over his ears in lopsided fashion, like a tent that has lost one of its moorings.

And he speaks the part as well.

"The more I think about it," he rumbles, gruff and defiant. "The more it pisses me off."

With that, the self-professed "Godfather of Gangsta Rap" points to the far end of the strip mall in which he stands, in front of the now-shuttered Tropicana Cinemas, a barren celluloid graveyard nestled next to the Pinball Hall of Fame and Putters sports bar.

"There was a line of cops all around the whole place here," the 70-something music industry maverick and grandpa of four says. "They had the entrance to the lot all blocked off."

In late April, Alexander had helped organize a teen-oriented hip-hop show at the venue featuring a 10-year-old MC named Lil One, but it was abruptly shut down by a fleet of police officers hours before it started.

The multiplex had hosted concerts before, but the authorities treated this one differently.

"With the rock shows, they had never bothered with anything," says John Bentley, who ran the cinemas at the time and spoke with the police when they arrived on the scene. "What happened was they came in there and said, 'We're not going to have this kind of show in this town. We don't have hip-hop shows in Las Vegas. It's not going to happen.' "

According to Las Vegas police, gang units often are sent to hip-hop concerts as a routine precaution in case any violence should break out.

"We understand that the majority of the crowds that go to hip-hop concerts are good, law-abiding people," public information officer Jay Rivera says of the tactic. "But it also has the tendency to eliminate some of the criminal element."

Still, this wasn't a gangsta rap show, wasn't something that catered to the thug crowd.

"We were clearly doing something positive to try and give these kids something to do besides being on the street," says singer/rapper Mo Wiley, a 31-year-old mom with a tattoo of a microphone on her shoulder who was set to perform at the concert.

Moreover, the artists themselves weren't averse to a police presence at the event.

"If they would have been standing there with a couple of cops and said, 'Hey, we're going to go ahead and search everybody down when you go in because we want to have a safe night,' I never would have complained," says Slick, a rapper/producer who was one of the headliners of the show. "We offered that, 'Hey, search us all.' "

Still the event was shut down, and legitimately so: It turns out the cinemas weren't properly licensed for concerts.

But Alexander isn't budging.

He takes issue with the fact that the event was targeted because it was a rap show.

"After the fact, they start looking at the guy's licenses. Way after the fact," he says, talking through a grim smile that conveys all the warmth of a Wisconsin winter.

It's no secret that tensions between local authorities and the Vegas hip-hop community have been simmering for years, ever since a police officer was killed by an aspiring rapper, Amir Crump (better known as Trajik of the Desert Mobb), during a shootout on Feb. 1, 2006.

In the aftermath of that incident, the Gaming Control Board warned casinos that they would be held accountable for any violence that occurred during rap shows and then-sheriff Bill Young called for hip-hop concerts to be banned from the Strip.

When the furor erupted, Alexander was one of the most prominent figures to speak up in the press for local rappers.

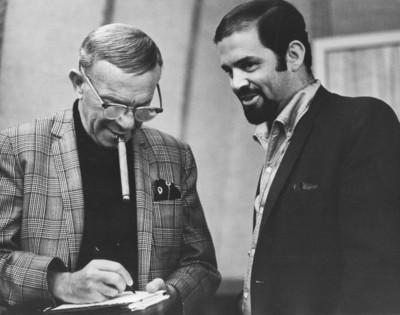

He has been an influential presence in the music industry for more than 50 years. Since beginning as a sales rep for blues label Kent Records in the late '50s, Alexander has produced dozens of records for blues greats such as Charlie Musselwhite and Harvey Mandel and worked with the likes of B.B. King, Etta James, and Ike and Tina Turner.

He has come to own the company that he started at, helped launch the career of one of gangsta rap's most significant acts, catalyzed the Latin hip-hop boom and mentored a who's who of significant record industry execs, from Arista Records VP Lionel Ridenour to the founder of Loud Records, Steve Rifkind.

"He's one of the originals," says Richie Rich, a former member of the L.A. Dream Team, which helped put West Coast hip-hop on the map in the '80s. "Morey Alexander and (fellow manager) Jerry Heller, they made the West Coast."

For an encore, Alexander has become one of the most ardent, outspoken and unlikely advocates for the Vegas hip-hop community: a grandfatherly white guy who you'd think would be retired on an island somewhere, donning khakis and ugly floral shirts instead of throwing haymakers at the powers that be.

But Alexander has remained committed to his cause, and he's still seething over his recent run-in with authorities, months after the fact.

"It's the worst crap in the world," he says of the concert shutdown, shaking his head in disbelief, grimacing like he just swallowed a bug. "And we're not going to allow it.

"I'm going to war here," he adds. "We're going to war."

FROM THE STREETS TO THE PENTHOUSE

"Do I look like a pussycat?" Morey Alexander asks, leaning forward in his seat a little incredulously, like a barroom tough guy after some brave fool has just ashed in his whiskey.

It's as if he can't believe someone would pose such a question without speaking rhetorically.

"I'm from the South Side of Chicago," he says with a chuckle, sinking back into his chair in his high-ceilinged living room, which is well-appointed with lush paintings and a beige decor. "You wouldn't go there today without at least a machine gun, OK? I can handle myself."

Alexander is good humored in general, as relaxed as a Sunday afternoon. He recalls his role in launching the career of randy comedian/actor/blaxploitation icon Rudy Ray Moore with a wink -- "I was the first person to put a dirty black record on the Billboard charts." He snickers proudly -- and peppers conversations with the occasional laugh that rattles out of his sternum like cannon fire.

He has taken hundreds of artists under his wing, and he has a welcoming, dependable air about him, like someone you could trust to feed your cat while you're away on vacation.

But Alexander also is a street-hardened former Air Force cadet and Golden Gloves mauler who claims that he was shaving at the age of 12. He has the thick forearms of either a dockworker or an ex-all-city wrestling champ -- Alexander was the latter -- and he speaks in the deliberate, pointed manner of someone who isn't used to having to repeat himself.

The passing of time has lowered his center of gravity a bit, and sometimes his gait is stiff and rigid, like a man beset with wooden joints. But Alexander's still a lively presence who reveals his inner bad ass with obvious relish at times.

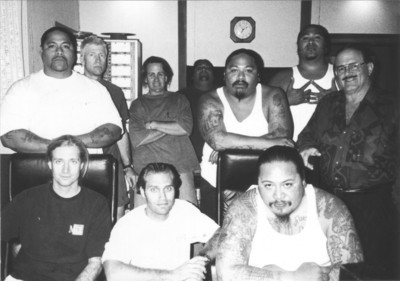

"I've managed a lot of tough, tough guys," he notes, mentioning Samoan wrecking crew the Boo-Yaa Tribe, among others. "(Death Row Records founder) Suge Knight threatened to kill me, that (expletive). I said, 'Come on ahead, I'll shoot ya before you walk through the door, that's all.' "

Alexander first made a name for himself as the rare white guy who wasn't seen as an interloper in the inner city, someone who could successfully mine talent from the harshest of ghettos because he, too, hailed from one.

"I don't think I ever had a prejudiced bone in my body. I guess people could feel that," Alexander says of his ability to win the trust of black artists. "I had guys like Jimmy B., he was a partner of mine, an R&B singer that I had at Kent, he always used to say to all the guys that we were hanging with, 'Hey, you see that guy? You think that's white? He's blacker than you'll ever be.' "

As a kid, Alexander worked at the family pharmacy smack in the middle of one of Chicago's most rugged stretches.

He came of age in a fertile era for the blues, when artists such as Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Freddie King and dozens more future legends were migrating to the Windy City from the South and amplifying the genre with electric guitar.

At 15, Alexander started sneaking into blues clubs and immersing himself in the music, rubbing elbows with Phil and Leonard Chess, who would launch the seminal Chess Records, and George and Ernie Leaner, who helmed United Record Distributors, the country's first black-owned music distribution company.

"These guys were the pioneers, and we all grew up together in that area," Alexander says. "I remember those guys when they were kids. They're all gone. I'm still here."

After attending pharmacy school at Purdue University and enlisting in the Air Force for a time, Alexander embarked on a career as a salesman, developing a novel concept with his partner at the time: selling perfume in liquor stores.

A business associate of theirs who worked for Kent Records convinced the two to take some blues albums to the stores with them -- a tough sell, they thought at the time, but they agreed to take the records, not expecting much.

The albums were an instant hit.

"The stuff sold out in three days," Alexander recalls. "Next thing you know, we've got 10,000 accounts, 125 employees and we're going crazy."

While we're accustomed to seeing CDs for sale at retailers such as Wal-Mart and Target nowadays, back then, to find records outside of a music shop was unheard of.

But Alexander had hit upon a new business model of selling albums in nontraditional outlets, and he ran with it to great success. Soon, he was shipping thousands of records at a time to department and drug stores.

Alexander would buy the records in bulk at discount prices and sell them to the stores for a dollar apiece, a huge markdown from the standard price of $3.98, which albums normally cost. Cheap records -- or cut-outs, as they're known today -- were rare in those days.

Alexander's sales pitch was simple: "Give us 10 feet, we'll make you more money than you could make with anything else you have in the store," he says. "And we did. We had all the big chains: Krogers, Walgreens, Macy's. We'd ship in 40,000, 50,000 records and they'd sell out in a day, two days, because there was no such thing as an album for a dollar. They'd put them out in the bargain basement or whatever, and the stuff would sell out like crazy."

Eventually, Morey would be asked to run Kent, which he would later buy and still oversees today along with his hip-hop label, First Kut Records, tending to business most every day of the week.

Along the way, he would start an artist management and development firm, produce numerous albums and eventually relocate to Los Angeles, where he had a penthouse suite across from Tower Records.

It was there that Alexander would earn his future nickname: "The Godfather of Gangsta Rap."

"At that point, we were right in the middle of everything," Alexander recalls. "That was really the hotbed of West Coast rap. Right there."

BULLETS AND BLOODSHED: GANGSTA RAP'S VIOLENT BIRTH

There's a mess of gold and platinum at his feet, a bullet-ridden hit parade, and the stories that they tell are penned in blood, sweat and, well, lots more blood.

"I don't have room for any of these things," Alexander says, thumbing through a stack of shiny, glass-encased plaques commemorating big sales for such hard-nosed artists as N.W.A., Eazy-E and Mellow Man Ace, which are stacked on the floor of his home office. "I've got a whole bunch of them out in the garage."

The room looks like the home base for some overworked college professor, paperwork strewn here and there, while the walls are a crash course in the history of the blues and hip-hop, with framed photos of this great and that.

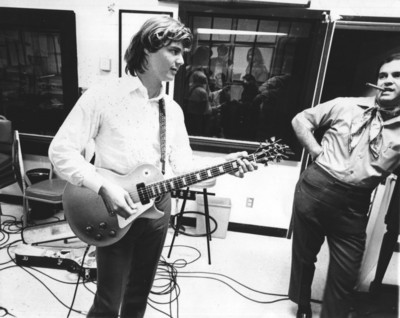

"That's Steve Miller. How about that?" Alexander says grinning and holding an old black-and-white portrait of the classic rocker way back in the mid-'60s when he was in the Goldberg-Miller Blues Band, which Alexander helped discover. "That was probably the best blues band I ever heard."

But throughout his 50-plus year career in music, one act looms larger than all the others in terms of notoriety, controversy and influence: gangsta rap pioneers N.W.A., a rap supergroup of sorts that hit you like a molotov cocktail hurled through your speakers beginning with its seminal 1988 disc, "Straight Outta Compton."

Billing themselves as "the world's most dangerous group," N.W.A. took on the cops and racial profiling ("F!@$ Tha Police"), spun blood-soaked tales of inner city drug peddling ("Dopeman") and brought the mean streets of South Central Los Angeles into the suburbs in violent fashion for a largely white audience.

Their tunes were gritty, remorseless and real, a loaded Glock to the temple of mainstream rap at the time.

"Really, they changed hip-hop," says Sean Fennessey, editor of popular urban music magazine Vibe. "They brought an attitude, a kind of sneer, that I don't think rap had ever seen before. They didn't put the West Coast on the map, but they certainly blew it up for everybody."

Alexander discovered the group when its conceptualist, rapper Eazy-E, came to him for help managing the group after it had started to have local success with its first release, the roughshod, independently released compilation album "N.W.A. and the Posse."

"Eazy was basically a small time dope dealer," Alexander says. "What happened was that nobody wanted to deal with that record, and the record was selling real well out of the trunk of cars and at the swap meets. So we could build a market, but nobody would play it. I took that record to every executive in the business practically, and they all said: 'Are you crazy? We can't do anything with this.' "

But Alexander pressed on.

He grew up on the block, and he knew that if something went over well on the streets at a grass-roots level, it was destined to resonate on a broader scale. Eventually, he helped find N.W.A. a record deal with a fledgling independent label.

"Since nobody else would sign them, we ended up with Priority Records, who were just starting," Alexander recalls. "Their big hit was the California Raisins. So finally, Bryan (Turner, Priority Records founder) says, 'OK, I'll try this.' And he gives me, like, $10,000 to spread around to radio. The record took off, and the next thing you know, they're being booked all over the country, Eazy is everywhere."

The group was a lightning rod for controversy, with MTV refusing to air the video for "Straight Outta Compton" because it believed it glorified gang violence, and the FBI sending a letter to Easy-E's Ruthless Records decrying the album (Alexander claims that the agency kept tabs on the group and tapped his phones).

Really, all N.W.A. did was offer a snapshot of one of the grimmest sectors of American society, a disturbing portrait to be sure, but it was authentic. We may not always like the reflection staring back at us in the mirror, but at least it's an honest one.

And so it was with N.W.A., with an anger that was righteous, raw and illuminating in all its ugliness.

"Gangster rap, especially in its early stages, really shed a light on something that was happening in black America that most people didn't know about," Fennessey says. "There was a grit and a realism there that you didn't find in almost any other genre."

Besides, not every member of N.W.A. was a thug -- far from it.

"Ice Cube never had a bad day in his life," Alexander says with a chuckle at the thought of the tough-guy MC turned actor. "He comes from an upper-middle class family. He's out bad-mouthing the world, in the meantime, he had a very nice upbringing."

Two decades later, Alexander still is baffled by all the flared tempers that N.W.A. elicited.

"It's only entertainment, you know?" he says. "Whatever it says, it says. It's no different than any of the other black music coming out of the '30s, when they were playing the blues, lamenting their tough times, which is what it's about."

After N.W.A., Alexander had success by helping launch the Latin rap boom with Mellow Man Ace, the first Latino MC to notch a million-selling single with his hit "Mentirosa."

Eight years ago, Alexander relocated to Las Vegas, where he still runs Kent and maintains an active release schedule, issuing everything from blues records to surf rock compilations to hard-core hip-hop discs.

He has made enough money to quit the game, but has little inclination to do so.

"I like being the boss," he says matter-of-factly. "It's simple."

STILL WORKIN' THE STREETS

At Head Hunterz barber shop, you can get a fade for $18, a mohawk for $30, a platinum cut for $100 and a verbal butt kickin' for free.

It doesn't cost anything to enter the shop's Freestyle Fridays rap battle -- scheduled the third week of every month -- except for a measure of your pride, perhaps.

The skinny white guy in the Pittsburgh Pirates ball cap and the oversized T-shirt learns this firsthand.

The master of ceremonies hands him the mic with strict instructions: "Sixty seconds homey, come from the dome," growls Mook the Barber, the store's proprietor, a stern looking man with a sinewy neck slathered in tatts. "The people around you are gonna judge, ya understand? Come from the head."

And with that, the DJ drops the beat, spinning from a pair of turntables positioned upon a stack of blue milk crates, nestled between a couple of black barber chairs.

Two aspiring rappers face one another in the middle of the room, standing where, 15 minutes earlier, piles of freshly shorn hair had lain.

Skinny dude's not off to a good start.

He's tentative on the mic, halting, a Shih Tzu yapping at a Rottweiler, and he tries to rhyme "Porsche" with "intercourse."

Mook's irritated.

"OK, now listen here, real quick," he barks. "If you ain't gonna come up here and get down, don't even get down. Man, serve this dude, homey."

He passes the mic to an intensely high-strung, wide-eyed dervish named J. Will, who lunges at his opponent like he just insulted his girlfriend (that would come later).

He delivers all kinds of unprintable dress-downs to his foe, who becomes a pincushion of blue insults.

The rap battle is a modern-day version of the dozens, where rappers attempt to demonstrate their mettle by cutting on one another in sledgehammer-to-the-kneecaps fashion, and J.Will is having his way with his opponent.

"Whatever it takes for me to win this, I'm not quittin'," he howls, throwing his limbs in the air with such violence it's as if he's trying to dislodge them from their sockets, getting so close to his challenger that Mook has to put his arm between the two. "I be spitting like gun ammunition."

The winner is determined by audience applause, and J.Will scores an easy victory.

Foil vanquished, he eventually makes it to the finals to face defending champ Mike Vegas, a stocky 22-year-old dressed in all black who has the confident air of a guy with a machine gun for a vocabulary.

Vegas puts J.Will on blast.

"You whack as dirt, you so black, you match my shirt," he booms to a round of guffaws.

He isn't finished.

"You know you can't harm me," Vegas announces. "You look like a crackhead who dropped out of The Salvation Army."

Shortly thereafter, Mook hands Vegas a crisp $100 bill as the winner of the event.

"This is where it all starts," Alexander says, taking the show in from the wings.

He's used to off-the-radar events like this.

Back in the mid-'80s, he organized hip-hop shows in roller-skating rinks on Crenshaw Avenue in South Central Los Angeles when clubs wouldn't take his acts.

Two decades later, he's still active in making his presence felt in the local music community. He arrives to the battle with a box of free CDs to hand out, and when the show ends, he offers to help sponsor the event in the future by offering studio time to the winners.

"They gotta have something, ya know?" he says.

The battle is filmed for broadcast on local music site All Hip-Hop All The Time (www.ahat.tv), which has been up since March and has notched some 40,000 hits since then.

"There's a lot of talent out here, but there's no strong venue for them to perform at," says the promoter who runs the site, a Vegas transplant who goes by the name OD, underscoring the need for spots like Head Hunterz.

There are a few regular hip-hop nights at various clubs around town, such as "What It Is Wednesdays" at the Ice House every other week, and the I Love Hip-Hop crew hosts shows at the Beauty Bar with some regularity.

But all told, there aren't that many outlets for aspiring MCs to develop their chops, especially those who are younger than 21 and can't get into nightclubs.

This is what makes Freestyle Fridays such a welcome vehicle for up-and-coming rappers.

"It gives people an opportunity to shine who don't normally have that opportunity," says local hip-hop promoter Brian Cooney.

"We don't have a place to hone our talent," adds Mike Vegas. "When Trajik did that thing with the cops, it actually shut down a lot of hip-hop."

No one knows this better than Alexander, who comes to events such as this to show his support for the scene.

"I always like to hang out, just to see what's going, what's happening," he says.

Alexander's a fatherly type, with two kids of his own, and he lends an ear to anybody who wants to talk to him about the business, dispensing with advice and passing out business cards.

After the show, he stops at the Village Pub next door for a quick drink. He's a sociable guy who enjoys a good cocktail and spinning yarns about his many years in the industry, dropping the names of so many former associates into the conversation, it's as if he has a Rolodex between his ears.

He doesn't suffer fools lightly, and there's an abundance of fools to weather in this business.

"They're just doing deals to do deals," he says of the industry's current woes. "Money's rubbing off in all the wrong places. That's why you've got no artist development and so few songs coming out this era that are even memorable. It's the dark ages."

By the time Alexander hits the road, it's nearly 10 p.m., and he has put in another long day.

The guy never seems to stop thinking about tomorrow, even if he knows it's never a given for him.

"I don't think I have a lot of time left," he says weeks earlier.

But Alexander has bigger things on his mind than such passing concerns as his mortality, the end of days or the sweet hereafter.

"It's time to break through with a hit," he says with yet another wink. "One more time."

Contact reporter Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476.