Organ donors in Nevada saving other lives

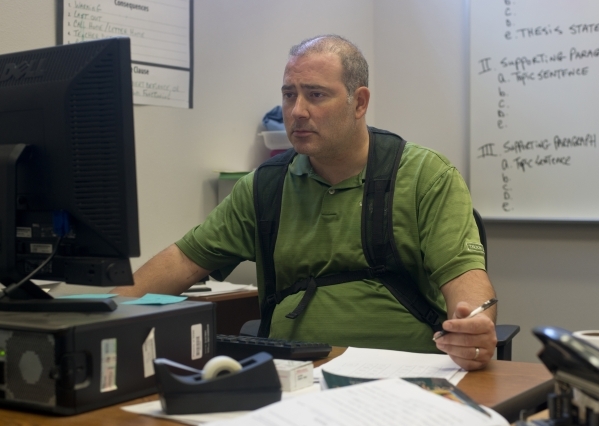

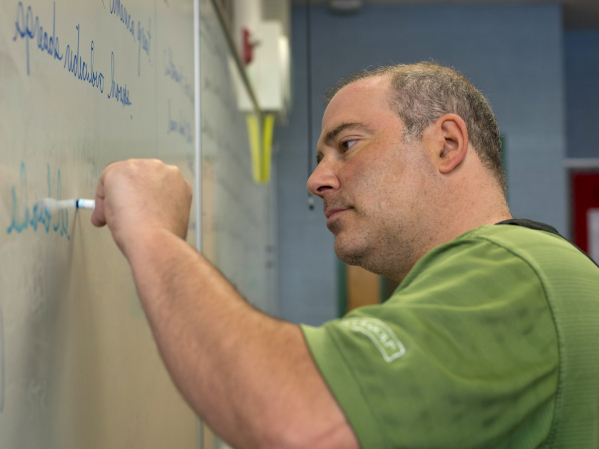

Martin Vece's life expectancy is less than other 45-year-olds in Nevada, even if he gets the heart transplant he needs.

The Canyon Springs High School English teacher is among about 560 Nevadans awaiting a transplant, their lives interrupted because less invasive treatments will not cure their ills.

Transplant patients face medical challenges and ongoing financial burdens that multiply exponentially when a donor organ becomes available.

But don't buy into a common misconception that potential recipients are just waiting for someone to die.

Wearing a left ventricular assist device that keeps his heart functioning, Vece is back at work after nearly a year off.

"In a way, my life is on hold because I need this transplant," the father of three girls said. "But I can't stop living. I can't stop playing with my girls. I'm going to keep doing everything I can until that call comes."

In organ recovery and transplantation, medical professionals, donation advocates and family members face life-and-death decisions. The process often depends on obtaining the permission of next of kin. Communication focuses on terms such as brain death, life support and procurement. In obtaining donation consent, clear communication can allay fears and improve outcomes.

"That's the most difficult part of our job, and that's what my staff has to contend with: getting the family to the point that they understand that their loved one is gone, and do they want to save someone else," said Joe Ferreira, CEO and president of the Nevada Donor Network.

The potential donor can be on a ventilator or other life support, and family members can see a heartbeat and the action performed by the ventilator, which inflates the lungs and causes the chest to rise. The patient still has body temperature.

That scenario often plays out after some traumatic event such as a car accident, stroke or brain aneurysm.

"Some families understand right away," Ferreira said. "For others, it takes longer, and at that point, the hospital is in a bind because when somebody has been declared clinically dead, there's no reason to keep them on the machines other than the potential to keep the organs viable.

"That creates a different dynamic. The families feel pressured, unfortunately, because the hospital says your loved one has been declared deceased, so if you're not going to donate, we're going to disconnect the machine."

Making Wishes Known

The numbers on organ donation in Nevada are mixed: At about 40 percent, Nevada is lower than the national average of registered donors, but the service area of the Nevada Donor Network has more organs recovered per capita than anywhere in the world, Ferreira said. Most of Nevada is covered by Ferreira's organization, but Washoe and Carson City counties are served by organ procurement organizations based in California.

An average of 79 people receive organ transplants each day in the United States, according to organdonor.gov. However, an average of 22 people die each day waiting for the call because of an organ shortage.

The easiest way to register to be an organ donor is to make the designation on a driver's license. People who want to be certain their desires are followed may register on the Nevada Donor Network's website.

Organ recovery officials also suggest people talk to family members because relatives can ensure intentions are carried out. Communication also helps eliminate any confusion or shock after a catastrophe.

"We don't want a grieving family member to be surprised by something like this," said Kate McCullough, supervisor of community services for Nevada Donor Network.

From 2000 through July of this year, 878 people in Nevada became organ donors after death, an average of 56 per year, according to the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

Natural causes accounted for 319 of those deaths, followed by motor vehicle accidents (139), non-motor vehicle accidents (65), suicides (64), homicides (56) and child abuse (nine). Other causes accounted for 225 of the deaths, and one cause of death was not reported.

Procuring the organs

The only kidney transplant program in Nevada is the Center for Transplantation at University Medical Center, which has performed about 60 kidney procedures per year. This year, the center is on track for about 75 procedures, UMC Transplant Services Director Gwenda Broeren said, and hospital officials are looking at expanding into liver and pancreatic transplants.

When Ferreira's staff has a donor, transplant surgeons such as Drs. John Ham and Bejon Maneckshana get the call. If all eight organs are being recovered, the process can take three to four hours, starting with the heart, then moving to the lungs, liver, kidneys, pancreas and intestines. The organs are clamped, and a chilled preservative solution arrests metabolic functions. During transplantation, clamps are removed, organs are rewarmed with blood, and function is restored.

The organs are assigned to patients based on lists maintained by the United Network for Organ Sharing, a nonprofit organization under contract with the federal government. Before an organ is allocated, officials weigh candidates' circumstances and medical needs, and they try to estimate the length of time patients and organs will survive. Geography also plays a role.

"Each one has a different algorithm based on how well that organ can survive transport or time out of the body," Broeren said.

In some instances, Ham, the medical director of UMC's Center for Transplantation, can recover a kidney at another hospital, then transplant the organ into a patient at UMC.

Most transplant patients in Southern Nevada must leave the area, but Dignity Health Nevada, the parent company of the St. Rose Dominican hospitals, has a cooperative agreement with Stanford Health Care in Palo Alto, Calif., allowing some Southern Nevadans to be screened without having to travel. Heart and liver specialists with Stanford Health work out of the St. Rose-Stanford Clinic in Henderson.

"The resources involved in creating and establishing a transplant program are enormous," said Kim Standridge, director of business and transplant outreach operations for Stanford Health. "You need to have a team dedicated to transplantation."

At Stanford Health, 102 medical professionals are dedicated to transplantation, performing about 270 procedures per year, involving the eight organs. Kidney-pancreas transplants and heart-lung combined transplants also are performed.

Donations From the Living

Most donated organs are from people who have died, but a living person can donate a kidney, part of the pancreas, part of a lung, part of the liver or part of the intestine.

This year, Brandon Moran was the recipient of a kidney from Jacob McCulloch. The 30-year-old Las Vegans have been friends since meeting as classmates at Cimarron-Memorial High School.

Moran was diagnosed with kidney failure in December 2013. McCulloch sympathized with Moran's daily dialysis treatments, finally saying, "I'm tired of seeing you like this."

In May, Maneckshana removed one of McCulloch's kidneys, and Ham transplanted it into Moran. McCulloch shrugs off any suggestion that he might have done something heroic.

"I hope other people would do the same," he says.

Vece, the Canyon Springs English teacher, is being kept alive by the left ventricular assist device, but complications include abdominal bloating, and he doesn't have the stamina he once had. He was 30th on the list in mid-September and had risen to 22 last week, patiently awaiting the notification that will signal his rebirth.

"That's the day I will consider my life to have started over again," he said.

Contact Steven Moore at smoore@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563.