After 60 years, soldier’s remains come home

For 60 years, Diane Kula didn't know what happened to her big brother, Don.

The soldier left with little notice. He spent a brief leave at their Bay City, Mich., home, in the fall of 1950 and left to fight a war in far-away Korea.

He told his family he would be gone for a couple months and would be home in time for Christmas to see his stylish, 14-year-old sister wearing her poodle skirt and saddle shoes.

"He just thought I dressed cool," Kula said, sitting on the sofa of her Las Vegas home. "He listened to me. ... He had a wacky sense of humor. He loved to pick up a broom and strum it, singing love songs."

Over and over, he would play Bing Crosby's "I'll Be Home for Christmas," a tune that Kula now describes as "a miserable song that I still can't listen to even today."

For her, Sgt. Donald Maurice LaForest never came home until today , when an Army honor guard buries his remains in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

"It is closure for me," she said Friday as she sat with her husband, Dick Kula, and an Army National Guard sergeant who would escort them to Washington, D.C. "It's such an overused word. But we brought him home. That's what this is about: bringing him home. And we achieved it."

In January, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command unraveled what had been a mystery about her brother, who at the time was a corporal with the 8th Cavalry Regiment. He had been shot in the ankle on Oct. 8, 1950, shortly after he had arrived in Korea, but the wound was not serious, and he was sent back to the front lines. Three weeks later, he was guarding his battalion's command post when it was overrun by enemy forces. His unit, Lima Company of the 3rd Battalion, saw heavy fighting that came down to hand-to-hand combat.

When it was over on Nov. 2, 1950, he had been captured with nine other soldiers and a translator from the army of the Republic of Korea.

Kula said never in her wildest thoughts did she think he had been taken prisoner.

"I thought I was so grateful for the idea that he had simply been shot and died in battle. But that's not what happened," she said. "It's one thing to die in battle, but it's quite another to be taken out in the field and executed. They had no weapons. They had nothing. They were just marched out there and executed."

Two soldiers who survived the execution, Pfc. Joseph Doherty and Cpl. Franklin Harding, told the story of the war crime, which violated the Geneva Convention, and it is contained in an inch-thick report from the Accounting Command.

The 11 POWs were taken to a farmhouse about a mile from the battleground where they were held until Nov. 16, 1950, when four North Korean soldiers arrived. They marched LaForest and his comrades to the edge of a rice field and told them to lie down. When they refused, they were shot where they stood. Without being hit, Doherty and Harding fell to the ground and pretended to be dead.

That night, the farmer waved to the two survivors to come back to the farmhouse. They carried out Sgt. 1st Class Lawrence Nolan, who survived the execution but was seriously wounded. He died the next day. The survivors eventually were released to U.S. forces.

The bodies of LaForest, the translator and the other six soldiers -- John G. Linkowski, Silas W. Wilson, Charles P. Whitler, Stanley P. Arendt, Harry J. Reeve and Charles H. Higdon -- were buried in a mass grave.

Kula remembers the night of Nov. 3, 1950, when her family was told that her 19-year-old brother was missing in action.

A Western Union delivery man shined a flashlight on their house number and knocked on the front door. The family was sitting around the dining room table playing cards. Nobody wanted to answer the door.

When her father finally did, he was handed a telegram that spelled out the bad news.

"That's the terrible thing about missing in action," Kula said. "You hold onto hope so much longer than you really, really want to. Killed in action, that's final. That's over. You can put it to bed.

"But missing in action? My mother had a nervous breakdown."

The news "left a hole that lasts forever," she said. "You have no idea when it's going to be over, and it took 60 years for it finally to be over. You always think, gee, maybe he escaped. And he was such a cutie, maybe some Korean gal took him in."

In 1953, the Department of Defense declared LaForest dead. But Kula said she always held hope that he might be among the prisoners of war.

The family tuned in to a marathon of radio reports on the release of ex-POWs. "I remember us all taking turns listening to see if his name came up," she said.

As five decades passed, the rest of her family -- her mother, father and four siblings -- tried to close that chapter of their lives. All but one, her oldest brother, Jerome LaForest, died not knowing.

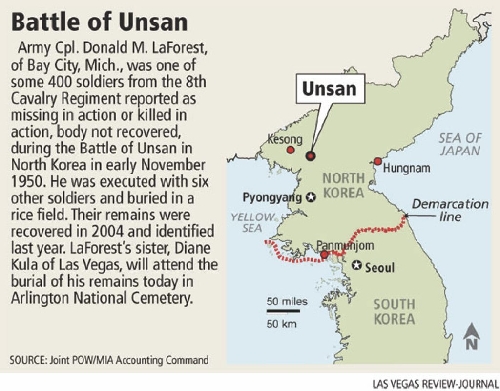

Then one day, Kula read an article in the Bay City Times about remains of U.S. soldiers found in North Korea in an area near Unsan. That's where a recovery team excavated a mass grave in May 2004 in a berm along a rice field.

"There was that memory," she said of Don, a proud young man with dark brown hair, blue eyes and a wide smile as he posed for his Army photo. "He was in that vicinity, and I just couldn't let it go."

She contacted the Accounting Command and offered to submit a mitochondrial DNA sample.

The command sent mobile blood units to her home in Michigan and to the home of her youngest son, Steven Butts, of Las Vegas.

After years of analysis comparing DNA samples with bone fragments, retrieving handwritten dental records and researching debriefing reports of the two surviving soldiers, who have since died, the command was able to confirm the identity of LaForest's remains in 2009, a year after Kula moved to Las Vegas.

She said she now has relief from the seemingly never-ending ordeal. A thought that comforts her is that the remains of Sgt. 1st Class Linkowski of Buffalo, N.Y., will be buried alongside Don's.

"It's almost like brothers that have been together so long and now eternity together. I just love that," she said.

Her advice to other relatives:

"Anyone who has anyone still missing, give your DNA. My God. Had I not."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.