Coming to Lake Mead: MX well groundwater

In 1979, the U.S. military began work on a short-lived scheme to hide a mobile arsenal of nuclear missiles in the Nevada desert.

The MX missile project quickly collapsed under the weight of its own cost and scale, but not before hundreds of exploratory wells had been drilled across the region in search of water for the effort.

Now these Cold War relics have become key components of the Southern Nevada Water Authority's plan to tap groundwater across the eastern part of the state.

The authority has teamed with the U.S. Geological Survey and Nevada Division of Water Resources to take periodic measurements from about 40 MX wells.

A few of the holes have been fitted with equipment to monitor them continuously.

The authority is using data from the old wells as it presses for federal and state permission to build a massive pipeline network into rural areas of Clark, Lincoln and White Pine counties.

Last week's state hearing on the Lincoln County portion of the water project included groundwater readings made possible by the MX project.

So did a 2006 hearing on the authority's plans in White Pine County's Spring Valley.

"I think it's cool. No data goes to waste," said Jeff Johnson, division manager for the authority's surface water resources department.

The notion is reminiscent of a certain Bible passage about beating swords into plowshares. But many rural residents don't see much difference between nuclear missiles and SNWA pipelines; to them, both look like attempts to exploit their quiet corner of the state.

"There is a strong sense of powerlessness," said Louis Benezet, who lives in the mountains east of Pioche.

On Feb. 8, he spoke out against the water authority's pipeline plan during a public input session held as part of the most recent state hearing on that project.

Benezet's family roots in Lincoln County date back to 1910. He became a full-time resident of the county in 1980, just as early work on the MX project was gearing up.

He said he protested the work back then because it was "indiscriminately tearing up the fragile desert landscape."

Since then, he and his neighbors have battled against plans for a hazardous waste incinerator in one nearby valley and rail routes in another that one day could carry radioactive cargo to Yucca Mountain.

"There have always been people who have wanted to put things here that other people won't put up with other places," Benezet said.

Steve Bradhurst understands the links between the pipeline and MX missile project as well as anyone.

In 1980, Nevada Gov. Robert List appointed him to head up the state office established to assess the MX project.

Bradhurst now serves as executive director of the Central Nevada Regional Water Authority, a coalition of eight rural counties launched in 2005 to study and protect water resources in those areas.

"It's sort of like we're back to the argument we had in '80 and '81 ... when it looked like rural Nevada was going to be a sacrifice area for the rest of the country," he said. "(Now) it looks like rural Nevada is going to be a sacrifice area for growth and development in Southern Nevada.

"It raises the same principal question: Doesn't this area have a right to a future?"

Then-President Carter pressed for the MX project, which military planners dreamed up as a way to protect the nation's nuclear missiles from a Soviet first strike.

The $30 billion plan involved the construction of up to 4,600 underground launch sites and a 200-mile "racetrack" on which rockets mounted horizontally would be shuttled from site to site. With no way to know which site had a missile in it at any given time, the Soviets would be forced to target them all.

"It was a shell game," Bradhurst said. "The idea was the rest of the country would be able to respond while Nevada and Utah disappeared. We would be the sponge to absorb Russia's nuclear arsenal."

The project would have affected 35,000 square miles in Nevada and Utah. Its proposed footprint took in seven Nevada counties and drew staunch local opposition.

"Before Yucca Mountain there was MX," said State Archivist Guy Rocha. "The overwhelming number of Nevadans opposed MX."

They needn't have worried so much. Carter's plan faded quickly. Ronald Reagan saw to that. Nine months after he was sworn in as president, he announced he was scrapping the plan.

By then, though, some 219 exploratory wells already had been drilled in 26 Nevada watersheds.

The U.S. Geological Survey eventually assumed control of the superfluous MX wells, including an especially large one that has proved important to the water authority.

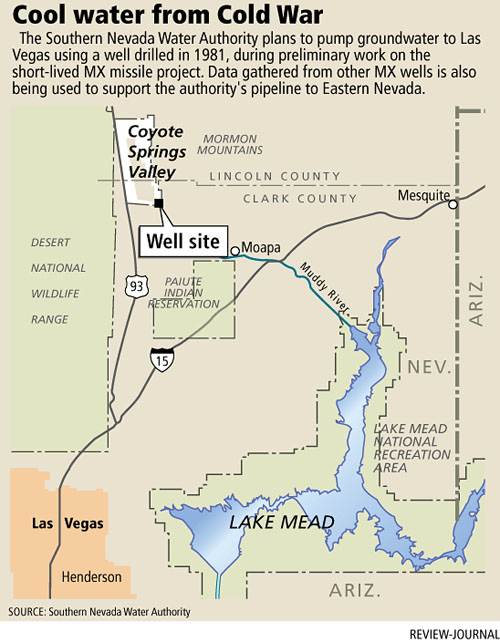

The hole known as MX-5 is located on the Pahranagat Wash in the Coyote Springs Valley, about 50 miles northeast of Las Vegas. When the Air Force drilled it to a depth of 626 feet in 1981, it produced what Johnson called "an incredible amount of water," nearly 4,000 gallons a minute.

Then the missile project petered out, and the federal government traded the well and the 42,800 acres surrounding it to defense contractor Aerojet in 1988.

Eight years later, the company sold the still-vacant land to high-powered Nevada lobbyist Harvey Whittemore.

In 1998, he persuaded the water authority to buy the well and about half of his water holdings in the Coyote Springs Valley for $25 million, the same amount he is said to have paid for the entire property.

Today, MX-5 is easy to miss. It's little more than a rust-covered pipe jutting a few feet from the ground just off state Route 168, a few miles east of U.S. Highway 93.

That will change in the coming weeks, though, when work begins on a 16-mile, $21 million pipeline that will allow the authority to use water from MX-5.

The water will be treated at the well site for elevated levels of arsenic and piped east to the distribution system for the Moapa Valley Irrigation District. From there, it will flow into the Muddy River and then into Lake Mead, where the authority will capture it using existing intake pipes.

"We anticipate moving water in late '09, early 2010," Johnson said.

When that occurs, it will mark the first time groundwater from outside the Las Vegas Valley has flowed from local taps.

If authority officials have their way, it won't be the last.

By 2015, they hope to tap billions of gallons of water a year from Eastern Nevada and pump it to Las Vegas through a pipeline that is expected to cost well over $2 billion.

The authority's case for its pipeline relies on data from the MX wells, particularly in Spring Valley where the agency plans to tap more groundwater than anywhere else.

The 1 million acre basin in eastern White Pine County is home to 17 monitoring wells from the missile project. Only Railroad Valley in Nye County has more MX wells.

"These wells are the only view we have into the ground. We need to see as many views as possible," Johnson said. "Anything out there that can be monitored, we're monitoring it. We're leaving no stone unturned."

Water authority General Manager Pat Mulroy compared her agency's use of the wells to another wartime project that has found a "peaceful application," the water line built from Lake Mead to the chemical plants in Henderson during World War II. That straw continues to supply lake water to Nevada's second largest city.

The MX project could prove almost as valuable. "Look at all the science we got out of it," Mulroy said.

"It has also saved the authority a little bit of money because drilling wells isn't cheap," Johnson added.

Rocha said, "Without taking a position on whether this water importation plan is good, bad or indifferent, I think it is a good use of something. If I was the Southern Nevada Water Authority, I would use this resource."

Bradhurst agreed.

"It's a credit to the water authority," he said. "They should be using any information that's available."

As for which project is worse, the pipeline or the missile array, Bradhurst said it's almost too close to call. Although a swath of land would have been closed off from public access had the MX been constructed, it "wasn't going to take a lot of water out of the ground," he said.

But as far as Benezet is concerned, the choice between well heads and warheads is no contest.

"The MX was totally outlandish. It was totally insane," he said. "I don't have anything good to say about the pipeline, but at least I can understand it."

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean @reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0350.

GOODMAN'S COMMENTS DRAW RESPONSE

COACHELLA, Calif. -- The head of a Southern California water agency called comments last week by Las Vegas Mayor Oscar Goodman "ridiculous and inflammatory" and is vowing a fight to keep farmers' fields irrigated.

Goodman stirred controversy when he said Las Vegas will meet its needs with the water used by farmers in California.

"No one is going to allow us to dry up," Goodman said at a news conference Thursday, according to The Desert Sun newspaper. "The Imperial Valley farmers will have their fields go fallow before our spigots run dry."

Coachella Valley Water District general manager Steve Robbins shot back Friday by saying: "I would have to say to a comment as bold as that: We'll see you at the battlefront."

Goodman was responding to a question about a study from San Diego's Scripps Institution of Oceanography predicting that Lake Mead could go dry by 2021.

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS