Doctors’ licensing irritating

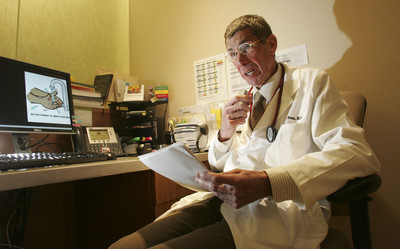

He has four U.S. cancer vaccine patents, has published more than 320 articles in peer-reviewed science journals and foots a résumé that includes the University of Pittsburgh's Cancer Institute.

But ask Dr. Kenneth Foon why it took him six months to prove to the Nevada State Board of Medical Examiners that he was competent enough to treat patients here and he shrugs.

"The Nevada licensing experience was by far the most difficult I've ever gone through in my career,'' said Foon, head of the leukemia section within the Department of Hematological Malignancies at the Nevada Cancer Institute. "I was recently licensed in Florida in half the time it took in Nevada, because they didn't require verifications to the level required by Nevada.''

And Foon's licensing experience might be considered quick compared to other physicians', said state Sen. Joe Hardy, R-Boulder City.

Hardy, a physician himself, said he recently spoke with an ophthalmologist about his licensing experience and was told it took seven months.

"I thought that was a pretty quick turnaround. Everyone in the nation knows, 'Don't go to Nevada. It takes too long to get your medical license,''' Hardy said.

"If I'm someone coming off a residency with $200,000 in medical school debt, and I have an opportunity to get my medical license and start earning a living in a state within two weeks versus six to nine months, where do you think I'm going to go? Not Nevada.''

Though Hardy and other state lawmakers and physicians agree stringent laws weed out bad doctors, they also say those laws shouldn't prevent doctors from coming to Nevada.

When that happens, it adds to the state's physician shortage, which could impact access to care for patients of all ages, health officials say.

Hardy said lawmakers are "ready to do whatever it takes" to make a change.

He said lawmakers plan to work with the medical board to come up with solutions, even if that means changing state laws at the upcoming Legislature.

Foon applied for his medical license in early April; he received it in September after navigating numerous hurdles.

One obstacle, he said, occurred when a credentialing specialist for the Nevada Cancer Institute tried to obtain his records from UCLA's medical school, where he was a fellow from 1979 to 1980.

Heather Murren, president of the Nevada Cancer Institute, said the facility has credentialing specialists who assist physicians with their licenses and hospital credentials.

Even with the extra assistance the process can still take up to a year, Murren said.

The credentialing specialist who helped Foon was told that UCLA's records only date back 10 years.

Also, it took the credentialing staff four attempts to receive verification from the Washington VA Medical Center in Washington, D.C., that Foon had completed his internal medicine residency there.

The Nevada Cancer Institute's staff "spent hours on the phone pleading with disinterested clerks to connect us with the appropriate people," Foon said.

"When we found these individuals, they were equally unhelpful or clueless as to what to do. I then began to contact senior physicians who were present during my training at various institutions to send letters to the board to verify that I trained at the institution.''

In the UCLA case, Foon ran into a different problem: The records no longer existed. He said the medical board asked him to get signed letters from physicians who were present during his training stating that the original records didn't exist.

"This delayed the process by months,'' Foon said.

Foon said the fact that he was board certified in internal medicine, medical oncology and hematology should have been enough verification for the medical board that he had been trained in those fields.

If he wasn't, he never would have been board certified in the first place, Foon said.

Murren called the state's medical licensing process archaic and noted it not only disrupts hiring, but cuts into a physician's opportunity to expedite hospital credentials as well as begin seeing patients.

She said physicians interested in practicing in Nevada, especially those in research, are "turned off" by these obstacles.

Hardy, a member of the state's Legislative Committee on Health Care, made similar comments.

He said a slow, bureaucratic licensing process isn't helping Nevada change its image, nor is it helping the state's physician-to-population ratio.

Nevada ranks 45th among states in its number of doctors per capita, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

According to the Nevada State Board of Medical Examiners' 2007 annual report, there are 159 active in-state medical doctors per 100,000 residents.

The national average is about 260 doctors for every 100,000 residents.

In that same report, the board noted that Nevada has issued an average 314 new licenses per year since 1980. But because of the state's population growth, the ratio has seen only a slight increase, of 15 doctors per 100,000 residents.

And according to an August report by the American Medical Association, 41 percent of Nevada's practicing physicians are approaching the retirement age of 50 and older.

The report also says that in 2007, none of the 453 applications for medical licenses in Nevada were denied.

Louis Ling, the medical board's new executive director and special counsel, said he's heard the complaints about the lengthy licensing process.

Ling knows first-hand it can take some physicians up to a year to get licensed in Nevada.

"I just saw a file that's been open for a year, and I've asked our licensing division. 'Why so long?''' Ling said. "It should never take this long, but the reality of it is these applications require a tremendous amount of legwork and, to be fair, sometimes these physicians don't do what they are asked to do.

"Sometimes it's just not easy to get information. Regardless, we need to examine procedures and determine: Are there ways we can shorten the process?''

Ling said he and the medical board's staff are working on proposals that would do just that.

Those proposals, along with a few others that address internal and administrative issues, will be presented at the medical board's next scheduled meeting in December.

However, Ling said, medical licensing issues ultimately would have to be addressed in Nevada statutes. That's going to require legislative action.

He said Nevada's laws that govern medical licensing haven't been revised since 1985. The laws were written in the 1970s, he said.

Embedded in the Nevada Cancer Institute's White Paper, written earlier this month, are some suggestions regarding changing state law.

The paper, which was partly written by Murren, suggests the medical board do away with the paper application process in favor of online applications.

It also suggests the medical board should participate in the Common License Application Form.

The form, which was developed last year by a task force formed by the Federation of State Medical Boards, allows state licensing boards to accept key credentials such as medical education and training verifications online by another state that participates in the Common License Application. The federation is a nonprofit organization that represents the nation's 70 medical licensing boards.

Murren said going away from paper applications to an online process would be faster and provide an opportunity for physicians to check online the status of their applications.

"I hear consistently from out-of-state doctors who are just livid and insulted at some of Nevada's licensing regulations,'' said Assemblywoman Sheila Leslie, D-Reno. "Of course, we want safe doctors; but the pendulum has swung too far. ... We need a big injection of common sense.''

Ling said some physicians have a perception that members of Nevada's medical board are using their power to keep competition low. The state's medical board is made up of six practicing physicians and three public members.

Ling said his proposals would address the competition issue, or act as a buffer to prevent such a perception.

"That's a common accusation among all licensing boards in the United States,'' Ling said.

Although he now has a Nevada medical license, Foon said he never would have come to Nevada had the medical board not exempted him from retaking board exams.

"If this isn't turned around, the state will continue to lose physicians from this problem," he said.

Contact reporter Annette Wells at awells @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0283.