Warring lithium companies take dispute to Nevada Supreme Court

In one of the driest state’s driest basins, two lithium companies are fighting over what underpins the mining industry in Nevada: water.

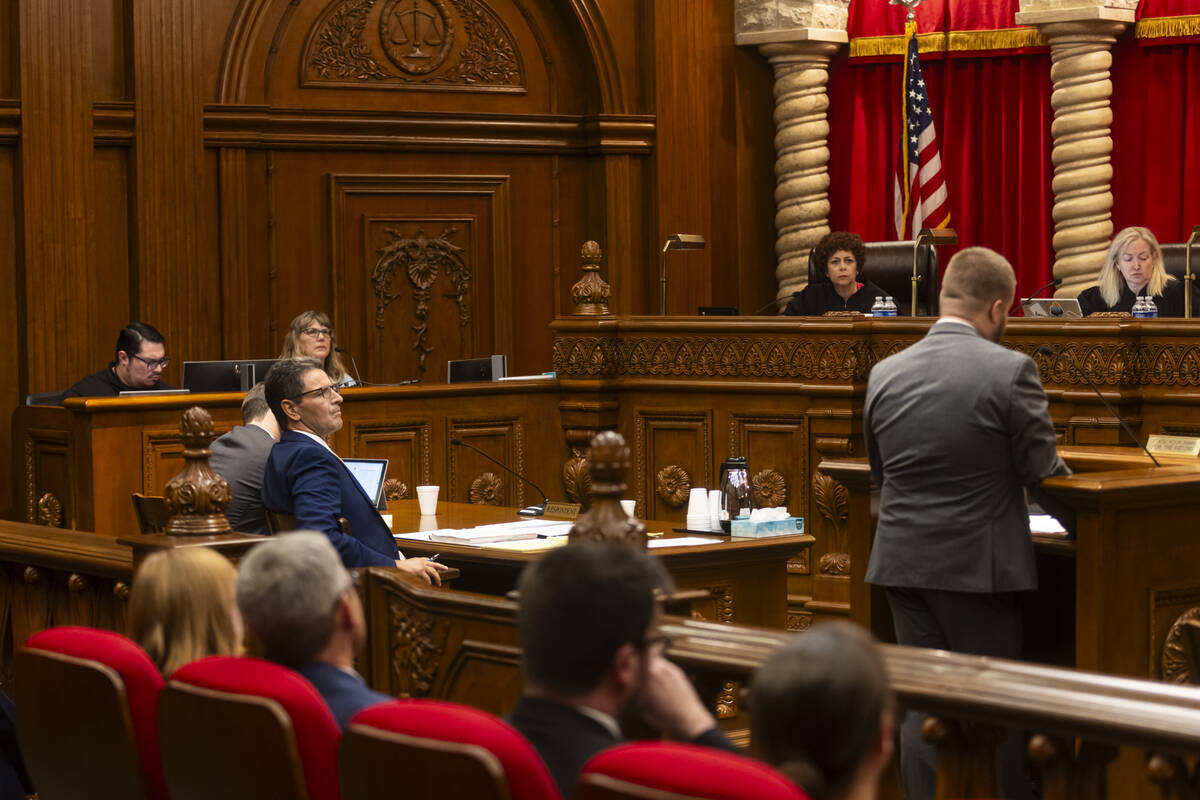

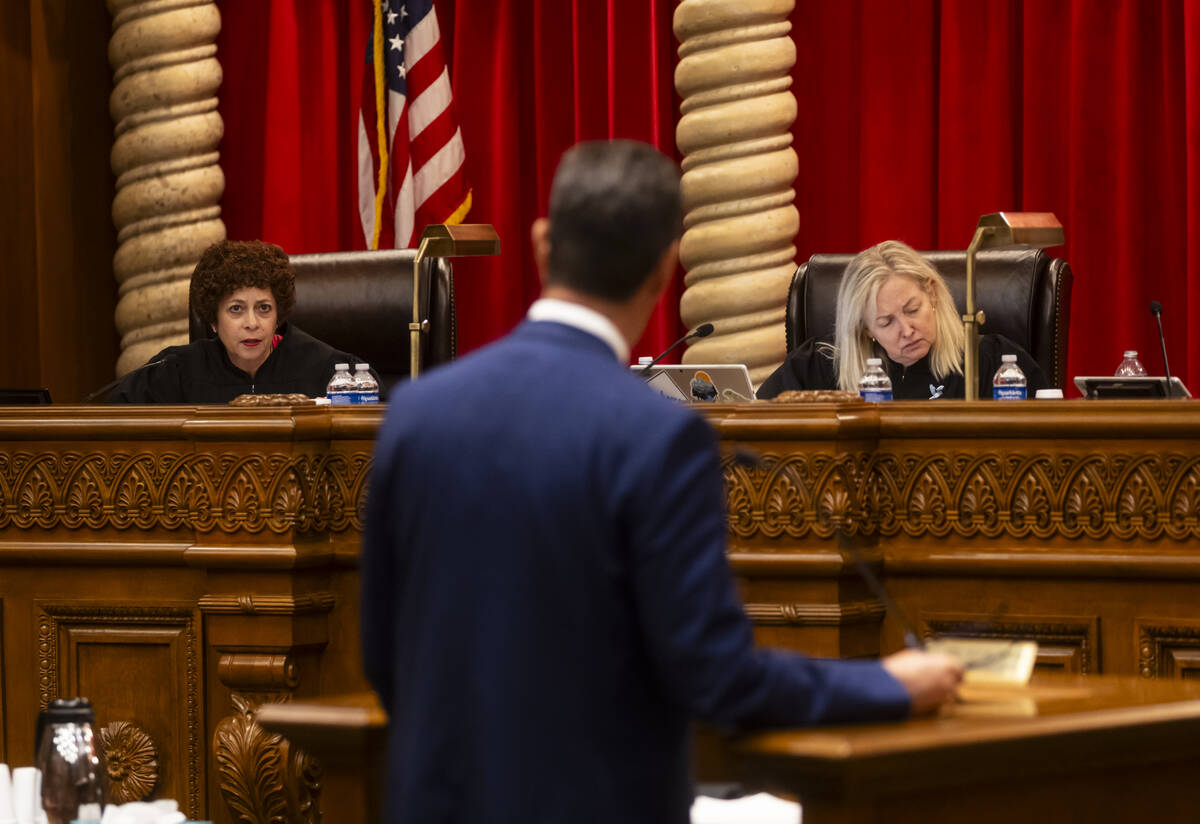

The Nevada Supreme Court heard arguments on Wednesday in a case questioning whether the nation’s only operating lithium mine can hold on to all of the water it’s permitted to pump — without actually pumping all of it.

“We ask you to remember the public asset of water and the preciousness of that resource,” said Paul Taggart, a water rights attorney representing Pure Energy, a company angling to obtain water rights in Esmeralda County for its own lithium mine. “No one should be allowed to hoard that public resource to exclude others.”

The legal challenge was brought by Pure Energy, which has been unsuccessful in securing the 2,500 acre-feet of water rights it needs to mine lithium. Nevada water law includes a use-it-or-lose-it provision, meaning that any water rights that aren’t proven to be put to “beneficial use” should be repossessed by the state.

Justices will decide whether the state engineer acted properly in granting Albemarle Corp. a time extension in proving that its expansion would warrant holding on to its full allowance of 20,000 acre-feet, or 6.5 billion gallons, of water.

That contested decision was made in 2017. Albemarle’s subsequent time extension requests have been left in limbo until the lawsuit is resolved, State Engineer Adam Sullivan said. The court could decide that Albemarle is no longer able to request time extensions, at which point the company could lose some of its water rights if it cannot prove it is using all of them.

The country’s only lithium mine

The mine in question — Silver Peak — is owned and operated by Albemarle, a chemical manufacturing company based in North Carolina. It has produced the mineral since the mid-1960s, long before national interest in electric vehicle batteries sparked a rush to find more of it.

Albemarle filed documents to seek federal approval to expand the Silver Peak mine this year. State regulators found that the mine was operating outside of its air pollution permits this year, as well.

Efforts to establish a domestic supply of lithium have been a top priority of Nevada’s state and federal leaders. China has remained the primary driver of the world’s lithium battery industry, with Chinese companies accounting for two-thirds of the world’s lithium processing capacity, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Near Silver Peak, interest in lithium has swelled. Another lithium mine, despite concern for a newly endangered wildflower, has obtained full permits from the feds: Rhyolite Ridge, proposed by Australian company Ioneer.

A district court remanded the Silver Peak case back to the state engineer, whose office held hearings on its decision in 2021.

The court sided with Pure Energy in 2023, calling the state engineer’s decision improper, and attorneys later appealed that determination to the high court.

Pure Energy’s mine would use direct lithium extraction, a method considered by some to be more sustainable, without the need for evaporation ponds. Albemarle intends to use the remainder of its water for expanded solar evaporation ponds, according to court documents.

Power of the state engineer

Attorneys for the state and Albemarle argued Wednesday that it’s not the court’s role to make such a technical decision about water.

The justices had the most questions for Taggart, who confirmed that Pure Energy believes Albemarle did not act in “good faith” or with “reasonable diligence” to prove it would use its full allowance of water.

Retired Justice Michael Douglas, filling in for a justice who was unavailable, said it was likely intentional that the Nevada Legislature did not include limits for how many extensions the state engineer could grant one company.

“We’re not the policymakers,” remarked Justice Elissa Cadish, in response to Taggart’s comments about how Pure Energy’s technology is more water-efficient.

With water rights in question, the drawn-out court proceedings have stoked fears among the 64 local employees who rely on the mine for their livelihoods, said Bradley Herrema, Albemarle’s attorney.

He said the company’s employee count makes Albemarle the second-largest private employer in Esmeralda County, Nevada’s most sparsely populated county, with fewer than 1,000 people.

Jordan Gregory Cloward, a natural resources lawyer with the attorney general’s office, said justices should consider the precedent that could be set by asserting that the state engineer did not make the right decision.

“This is not a case about whose new technology is better,” Cloward said. “This is not a case about whether Albemarle is able to predict the precise way by which it will use the entirety of its appropriation. Rather, this case is about the deference the state engineer is afforded when making a complex scientific finding of fact.”

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.