Historic house looking for a home

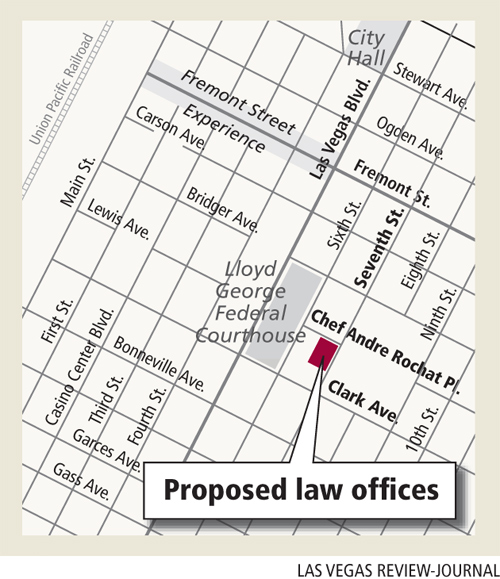

About a year ago, a developer wanted to build on property on the 400 block of South Seventh Street, but there was a hitch. The site includes a home that once belonged to Charles P. "Pop" Squires, one of the founders of Las Vegas, and city officials said there should be no development until the house finds a new home.

It's still there, but there's a new developer looking to build a five-story law office building, and the city's demand still applies, said Mayor Pro Tem Gary Reese, whose ward includes that block.

The demand is more complicated than simply finding a new place to plop down the house. For historical preservation to be successful, the preserved building must be used, even if that use is different from the structure's original purpose.

"The key thing on all of these historic structures is not just to save and restore the structure," said Bob Stoldal, local historian and head of the Las Vegas Historic Preservation Commission. "It's to turn them into living buildings again.

"They have to be saved through a function. A cultural center. A senior center. A youth center. Something that adds life back into the building."

Las Vegas, like many other cities, has a mixed record on historic preservation. But several successful projects have used the rejuvenation prescription.

Las Vegas High School, built in 1931, is now Las Vegas Academy of International Studies, Performing and Visual Arts.

The architecturally notable 1959 Morelli house was moved to Bridger Avenue downtown to save it from demolition and is now a museum and gallery owned by the Junior League of Las Vegas.

The former La Concha Motel's free-form concrete lobby was rescued from the Strip and moved to the Neon Boneyard, where it will be a museum building.

One of the most high-profile examples is the former federal courthouse and post office on Stewart Avenue and Third Street downtown, which is being restored and will be home to the Las Vegas Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement, aka the Mob Museum.

When the city acquired the building from the federal government, it did so with the understanding that it had to be preserved. Having it house a museum is supposed to help with downtown visitation, making historic preservation a commercial draw in addition to a civic good.

"It was never the goal just to preserve that building," Stoldal said. "It had to be something we felt would support the downtown development as well as contribute something culturally."

There have been disappointments as well. The remains of the Moulin Rouge casino were demolished earlier this year, despite decades of hope that the 1950s-era resort, which was the first to desegregate in the valley, could be preserved or restored.

The Huntridge Theater building is still standing at Charleston Boulevard and Maryland Parkway, meanwhile, and there are plans to renovate while keeping the building's distinctive architectural features. Those plans have not been acted upon, though, and the building sits mostly unused and empty.

Which fate awaits the Pop Squires house remains to be seen.

The property is part of the Las Vegas High School Neighborhood Historic District, which is on the National Register of Historic Places and is made up of houses built between the 1920s and World War II.

Unlike the Squires house, other properties are occupied, with most being converted to legal or professional offices.

The property is now owned by EVAPS LLC, which wants to build a 55,100-square-foot law office and parking garage on the corner of Seventh Street and Chef Andre Rochat Place.

The project already has the blessing of the Las Vegas Planning Commission, but the preservation requirement needs to be satisfied before the City Council weighs in, Reese said.

"I don't see any need to change it," he said, noting that the property owner has "two or three" leads on a new location. "They are looking to transport Pop Squires' house somewhere else."

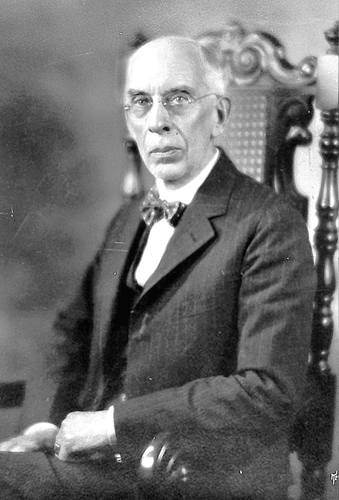

Squires watched Las Vegas history unfold as the city took shape from the early 1900s to the late 1950s.

He bought land in the 1905 auction that set up the city's core, established a bank and a hotel, and helped bring electric service as well as write the Las Vegas city charter.

He also was publisher of the Las Vegas Age from 1908 to the 1940s, and stayed on as editor when then-Review-Journal owner Frank Garside bought it.

Squires' wife, Delphine, played a leading role as well, being active in civic affairs and in the suffrage movement.

The house was built in 1931 and is an example of the Spanish Revival architecture style, which includes features such as low-pitched, red-tiled roofs with little or no overhang, stucco walls and asymmetrical facades.

Squires moved to it from his original Las Vegas home on Fremont Street and lived there until his death in 1958.

"Between the two of them, they were the parents of Las Vegas for a long time," said Stoldal.

Contact reporter Alan Choate at achoate@reviewjournal.com or 702-229-6435.