Utah rejects water deal with Nevada

In a move that could trigger a water war, Utah Gov. Gary Herbert said his state will not sign an agreement with Nevada over how to share a vast groundwater basin targeted by thirsty Las Vegas.

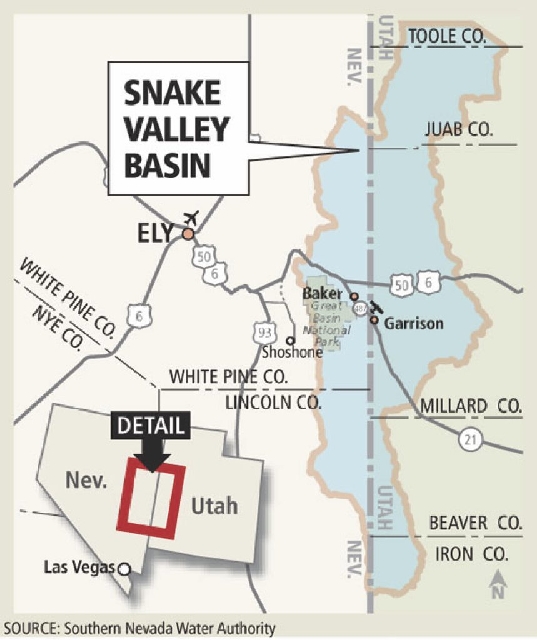

The Snake Valley water agreement was struck in August 2009 after four years of private talks among representatives from the two states. Nevada officials quickly signed off on the finished document, but their counterparts in Utah never did.

Herbert announced Wednesday that the deal is as good as dead.

“My decision was made as I visited with the good people who live in Western Utah — those most affected by the outcomes,” the Republican governor said in a statement. “A majority of local residents do not support the agreement with Nevada. Therefore, I cannot in good conscience sign the agreement because I won’t impose a solution on those most impacted that they themselves cannot support.”

Herbert’s decision could spark a legal battle between Nevada and Utah over the Snake Valley and other shared aquifers. Such a dispute probably would land in the U.S. Supreme Court and could threaten years of cooperation among the seven states that share the Colorado River.

John Entsminger is deputy general manager for the Southern Nevada Water Authority, which wants to pump as much as 51,000 acre-feet of groundwater a year from Snake Valley and pipe it south to supply more than 100,000 homes.

He said his agency plans to meet with state officials in Nevada “very soon” to craft a response to Herbert’s action.

“Frankly, we’re a little baffled by the motivations,” Entsminger said.

The water-sharing agreement was mandated by Congress in a 2004 lands bill and painstakingly negotiated by representatives handpicked by the governor of each state.

Now Herbert has chosen to ignore both the congressional directive and the advice of his own negotiating team, Entsminger said.

“We can’t simply accept the governor saying, ‘We’re not going to sign,’ and live with it,” he said. “Congress directed the two states to reach an agreement. Congress did not give one state the authority to prevent the other from developing water resources within its own borders.”

Last year, federal regulators signed off on the water authority’s proposed pipeline to eastern Nevada, but they had to exclude the portion of the project in Snake Valley because no interstate agreement had been struck.

Leo Drozdoff, director of the Nevada Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, said state officials are “evaluating all of our options in light of Governor Herbert’s decision.”

“This agreement was negotiated over many years and in good faith,” Drozdoff said. “We are disappointed by this decision.”

Snake Valley covers an area roughly the size of Delaware but is home to just a few scattered towns and farms.

Roughly two-thirds of the basin is in Utah, which is where most of the water use occurs. Nearly all of the basin’s recharge comes from the Nevada side of the line, where the north-south ridge of the Snake Range rises above 13,000 feet to comb rain and snow from the desert air.

The mountains are home to Nevada’s only national park and its second-tallest peak.

The agreement would have divided groundwater in Snake Valley between Nevada and Utah and provided protections for farmers, ranchers and other residents.

It also could have cleared the way for the authority to tap the basin someday.

Under the pact’s central provision, the negotiating teams for the two states agreed on how much groundwater the basin contains and how it should be divided: 132,000 acre-feet per year split right down the middle.

The 66,000 acre-feet set aside for each state included current water allotments, an amount deemed available for future use and a block of water to be held in reserve pending further study.

One acre-foot is enough water to supply two average Las Vegas homes for one year.

As part of the agreement, Nevada agreed to delay a hearing on the authority’s water applications in Snake Valley for 10 years to allow time for additional environmental studies.

Authority officials insist they have not committed to the controversial project, which could wind up costing more than $3 billion for construction and another $12 billion in financing and inflationary costs.

The plan dates back almost 25 years, when Southern Nevada water officials launched a grab for unappropriated water rights across rural Nevada.

Back then, the pipeline was meant to supply growth in the Las Vegas Valley. Now it is being touted as a backup supply for a community that gets 90 percent of its water from an overtaxed Colorado River and a shrinking Lake Mead.

Water authority General Manager Pat Mulroy has said the pipeline might have to be built even without a spur to Snake Valley because the Las Vegas Valley will need the water to survive.

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.