Record setters travel unarmed through Iran

What kind of weapons are you carrying?"

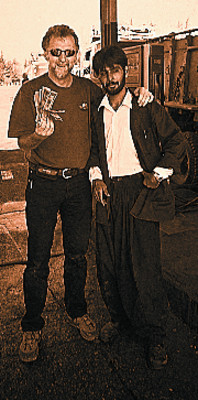

And the matter-of-fact way that Ahmad Homayouni asked that question made me feel even worse. His relatives, gathered around the table at his cousin's home in Kerman, Iran, seemed to be staring right through me.

"Well, we don't have any weapons," I replied.

I didn't like where this was headed.

Fifteen seconds. It seemed like an eternity. There was silence in this immense house with a garden in the living room. The half dozen Iranians stared at me as if I was crazy to be heading out unarmed on the desolate 400-mile road through Pakistan's Sandy Desert paralleling the Afghanistan border.

The ensuing conversation confirmed my suspicions about security in West Pakistan. Ahmad and his family explained that the area we were about to drive through was rife with smugglers moving 3-cent-a-gallon Iranian gasoline into Pakistan. It was a region where tons of the world's opium and hashish start the journey to Western markets and where gun runners arming Afghani rebels surface from time to time.

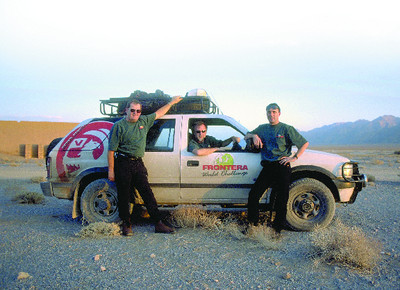

To make matters worse, my new friends assured me the transportation of choice for many of these operatives was four-wheel-drive sport utility vehicles. I eyed our grimy four-wheel drive Vauxhall Frontera out front in the driveway. The spare tires and satellite communications antennae on the roof made it look like a sitting duck.

In the fading desert light, I could just make out the logo on its front door, Frontera World Challenge. A chant from the mosque down the street filled the air. The heat was stifling. I was exhausted.

My partners, Welshman Colin Bryant and Scottish-born Graham McGaw, were down the street at the Kerman Grand Hotel. They were trying to overcome a technical glitch in our procedure for uploading digital images back to our logistics office in Canada and the press center in London, England.

Colin, a retired police officer who spent much of his career driving British heads of state around Wales, was about the best driver I had ever been with in a car. Witty and charming, focused and stubborn, he had already wrestled our overloaded Frontera through many dicey traffic situations.

Graham knew every nut and bolt in our vehicle. He worked as an engineer at the plant where the Frontera, the European version of the Isuzu Rodeo, was manufactured in Luton, England.

Since leaving England, we had driven pretty well nonstop. Western Europe was straightforward. Aside from a two-hour traffic jam in Vienna and torrential downpours in Serbia, the 38-hour drive to Sofia, Bulgaria, was a good warm-up. Then it was pea-soup fog through the mountains of central Turkey and temperatures of up to 110 degrees Fahrenheit in the desert areas southeast of Tehran.

The rules for the around-the-world driving record we were attempting to set in 1997 stipulated that we had to drive at least 28,000 miles. Backtracking was not allowed and we had to finish with at least two of the three of us in the car. The route had to pass through two antipodal points, places on the earth's sphere that are diametrically opposed to one another. Our antipodals were Gisborne, New Zealand, and Sagunto, a town just outside of Valencia, Spain.

The clock ran during the continental transits only. Turn it on in London. Turn it off in Chennai, India. On in Perth, Australia. Off in Sydney and so on. So with five stages, the attempt became five record runs with breathers in between where we transformed ourselves into logisticians, documenteurs and administrators.

And finally, the big ugly. No speeding. Get caught speeding and it's over in the eyes of Guinness Superlatives, who were sanctioning the attempt. There were a thousand things that could have ended our World Challenge, but the idea of disqualification for a speeding ticket didn't excite any of us. And, since the only way to guarantee one didn't get a ticket was not to speed, we didn't. It actually kept the stress levels down and we still managed to cover an amazing amount of territory every day.

All the way through the Sandy Desert, I thought about my three young daughters back home: Lucy, Natalie and Layla. With them in my mind, every vehicle we passed had me on edge. Are they smugglers? With guns?

Suffice to say that we made it through the desert without incident. It took three days to get through Pakistan to New Delhi, India. On the second day, the road was so rough we covered just 375 miles in 17 hours. Then it was floods in Multan, bribes to get us out of Pakistan and a hair-raising 11-hour night drive along India's Grand Trunk Road passing six fatal traffic accidents along the way.

We arrived in New Delhi at 3 a.m., maneuvering through a smoggy, ragged fog. Pulling up to our hotel, I thought about Ahmad Homayouni and his relatives back in Iran. I couldn't wait to tell him we had made it to New Delhi in one piece ... with no weapons.

Garry Sowerby, author of "Sowerby's Road: Adventures of a Driven Mind," is a four-time Guinness World Record holder for long-distance driving. His exploits, good, bad and just plain harrowing, are the subject of World Odyssey, produced in conjunction with Wheelbase Communications. Wheelbase is a worldwide provider of automotive news and features stories.