Cancer, mercury and extraction: Nevada mining town, near Thacker Pass, has polluted past

MCDERMITT — It’s nearly impossible to find a family in McDermitt that hasn’t been scarred by a cancer death.

Flanked by the Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation to the south and north, the town’s families — both Native and not — are well-acquainted with the politically powerful and often extractive mining industry.

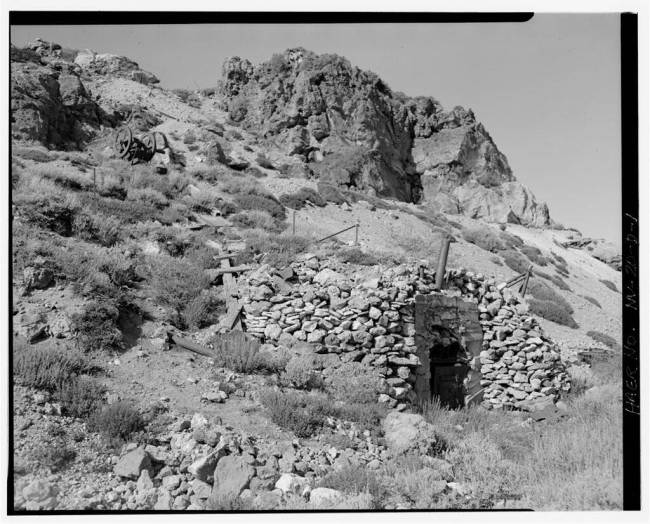

Five mercury mines were once the economic lifeblood of McDermitt, a small town that straddles the Nevada-Oregon border. The Cordero and McDermitt mines, a constant source of pollution that the federal government eventually invested in cleaning up, sit rusted and abandoned at the end of an unpaved road behind a fence with signs warning of contamination.

Today, three years after Humboldt County successfully lowered the town’s arsenic levels in drinking water to below federal limits, the mining town is a shell of itself — the only businesses left being the worn-down Say When Casino and three gas stations.

But another promising mining sector is at the crossroads of this town’s storied history: lithium.

The Thacker Pass lithium mine — the environmental review of which was fast-tracked and approved in the final days of the first Trump administration — is a hotbed of controversy for the fewer than 400 McDermitt residents who live about 50 miles northeast of the construction site.

“Growing up, you heard of cancer,” said Deland Hinkey, a 49-year-old Fort McDermitt tribal member who is staunchly opposed to the new lithium mine. “They got cancer, they died of cancer. There’s never been a feasible study up here on the cancer rate, and nobody wants to do it. Nobody wants to see it.”

The newest mining project has been called Nevada’s ticket to monopolizing the green energy transition because of the need for lithium batteries. But alongside the mineral that prospectors seek, they are digging up a complicated past and a long-buried, fraught relationship. And any new mine will change rural high desert living yet again.

Water woes are deadly for some

The water fountains at the McDermitt Combined School and the town library have long been taped off to prevent use, Hinkey said.

It’s a well-established fact that drinking from the public water system is not encouraged. The reservation operates its water independently of the town’s water system, which the county began managing in 2019.

The Fort McDermitt tribe garnered statewide attention in the 1960s when three infants died from “deplorable” health and sanitation conditions, according to news accounts and letters obtained from the files of U.S. Sen. Howard Cannon, housed in UNLV’s Special Collections.

In a 1965 Reno Evening Gazette article, then-tribal Chairman Art Cavanagh said an adequate water system for the reservation was his top priority. If not, he said the tribe “might lose some more babies.”

Cannon and U.S. Sen. Alan Bible pressed federal agencies to improve conditions. By May of that year, emergency work to establish a temporary water system was complete and a medical officer was assigned to work on the reservation.

Despite Cannon promising it in news articles at the time, the $100,000 needed for a permanent water well on the reservation was not appropriated in the Interior Department’s 1966 budget, according to an internal memo.

Arsenic is naturally occurring in the Nevada desert, but levels in the town didn’t fall below acceptable Environmental Protection Agency limits until 2022, according to county water quality reports sent to customers. Until that happened, residents of the town had the option to get bottled water delivered for free from the county.

“Any community that has experienced mining knows that there are long-term consequences,” said John Hadder, director of the environmental watchdog Great Basin Resource Watch. “Mining operations can often result in contaminants being liberated from natural sources and the concentration of them.”

The advocacy-oriented Environmental Working Group’s tap water database, which asserts that many EPA contaminant levels are too high to ensure safety, shows McDermitt’s water with nine pollutants of concern. Most of them — including an arsenic level that the group still considers 1,692 times too high — are linked to cancer.

Tasha Stoiber, a senior scientist with the organization, said in an interview that any one factor, such as drinking water, being tied to high cancer rates is a topic that requires much study.

Stoiber insists that the continued ingestion of drinking water, even when it’s below EPA standards for arsenic, can increase the risk of developing cancer over time. And smaller communities such as McDermitt often have less resources to treat their water, she said.

“When we’re extracting minerals from deep within the earth, this can cause all kinds of disruptions,” Stoiber said. “Arsenic levels in the groundwater in that area are fairly high — much higher than what public health goals would point to as safer for people.”

‘Dramatic changes’

In a statement, after declining an interview for this series, Lithium Americas spokesman Tim Crowley said the rampant environmental harm of historic mines has been remedied with regulation.

A suite of state and federal laws are aimed at preventing mines from polluting the environment, from the 1989 Nevada laws that created the Bureau of Mining Regulation and Reclamation to the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 that mandates federal environmental reviews with public input.

The Canadian company is committed to following those laws to “meet or exceed all applicable requirements, with comprehensive measures to mitigate and monitor impacts to wildlife habitat, water resources, and air quality,” Crowley said.

“Comparing legacy projects like Cordero and McDermitt to the Thacker Pass project is misleading and ignores the dramatic changes that have occurred in the United States, and in particular Nevada, that help ensure excellent environmental stewardship,” Crowley said. “The historic impacts in McDermitt arose from mercury mining that ran from the 1930s to the early 1990s, before modern safeguards existed.”

In McDermitt, however, the political clout of mining is nothing new.

The McDermitt mercury mine all but killed a proposal to add 19,000 acres to the Fort McDermitt reservation. Cannon, Nevada’s Democratic senator who served from 1959 to 1983, was considering sponsoring the proposal in 1978.

McDermitt Mine manager V.V. Botts, also chairman of the town’s community board, was one of a dozen residents who sent Cannon letters opposing the land transfer, citing concerns about water conflicts with ranchers and stifling the growth of the town. An out-of-town mining executive, sent a letter, too.

Cannon declined to move forward with the legislation after community backlash.

According to Humboldt County Manager Don Kalkoske, the water in town is more than safe following the installation of the arsenic plant that was funded with roughly $500,000 from the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection’s drinking water revolving loan fund.

Most of the residents he’s spoken with are glad the problem’s been dealt with and trust the water just fine, he said in an interview.

“For the most part, everybody is happy that we’ve got everything under control, and that the water is drinkable,” Kalkoske said.

A cancer cluster?

For decades in McDermitt, relatives dying of cancer has been a foretold conclusion.

Most reported instances of cancer clusters don’t turn out to be cancer clusters at all, according to the American Cancer Society, especially when the cluster occurs within a handful of families or the types of cancers experienced aren’t related.

“Investigators might have a few clear leads or starting points for common exposures among affected people, but they need to look at all the possibilities,” an information page at the American Cancer Society reads. “Finding the one exposure that could be the cause can be like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

As a child on the reservation, Hinkey said, he remembers playing with a gray mercury slurry his friend’s father brought home from his shifts at one of the mines. That miner, like most, died of cancer, Hinkey said.

An old plan of operations for the McDermitt Mine obtained from the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology details the procedure for employees whose blood tests came back high for mercury. Those workers were downgraded to a “low-exposure job assignment” until the mercury moved out of their system and they could pass another blood test.

Hinkey said his aunt is the only surviving mercury mine employee he knows of.

“To this day, we are still facing water contamination,” Hinkey said. “They’ve tried to fix it, but they can’t.”

Fergus Laughridge, health director for the Fort McDermitt tribe, said he’s managed the reservation’s clinic for five years, rehabilitating its financial health by making it an in-network health center for insurance providers.

Some of the mercury mine tailings eventually were used as foundation for homes in and around McDermitt, Laughridge said.

“We’ve seen some spikes in some cancers. Not sure what it’s attributed to,” Laughridge said, adding that “red hills” of mine tailings are still visible in some spots on the reservation. “It was later that they found out that stuff’s hot with arsenic.”

A Superfund site

McDermitt flew onto the radar of the EPA in 2009, said Harry Allen, an on-scene coordinator at the agency.

Parts of the town and the abandoned mines became a Superfund site at the request of community members after decades of toxic runoff that leached into the groundwater aquifer. The EPA Superfund program was established in the 1980s to clean up the country’s most hazardous waste.

Regulators excavated soil below the school’s playground and football field, installing a ground cover. The McDermitt Bulldogs football team was the subject of a 2018 Review-Journal feature, and later John Glionna’s book, “No Friday Night Lights.”

Officials removed soil from roads and 56 homes, too, with the project completed in 2013.

The normal range for mercury levels is 23 parts per million or lower, but some of the soil tested was more than 110 parts per million, Allen said. Arsenic levels were higher than recommended, as well, according to clean-up reports.

“If you’re exposed to that soil regularly, you’re going to get a little bit of that contamination each time you’re exposed, building up in your body to potentially give you a toxic or pre-cancerous effect,” Allen said.

The EPA’s online summary of the clean-up says Barrick Gold and Sunoco “declined to participate” in clean-up activities following unilateral orders that required them to. Neither company responded to a request seeking clarification as to why they declined or how they assumed responsibility for the sites.

EPA spokesman Alejandro Díaz said in a September email that Barrick paid $230,000 of the agency’s clean-up costs, but Sunoco never participated in the work that the EPA ordered. The EPA has communicated with the Bureau of Land Management on potential further enforcement, Díaz said, but he declined to comment on what that might entail.

Mining of the past — and the future

With her parents, Leanne Kemp, now 63, moved about seven years ago into one of the homes that the federal government cleaned up.

Out of her house, Kemp operates the Caldera Rock Shop — a garage-turned-living museum of the McDermitt Caldera, a region that’s a remnant of a supervolcano that formed around 16.4 million years ago. It’s a popular stop for rockhounders, with an online shop that regularly receives international orders.

Kemp drinks bottled water and nothing else, as do her neighbors.

“We’ve always known that the drinking water has arsenic in it,” Kemp said. “It’s better now, but I’m still kind of afraid to drink it.”

A prospecting company called Silver Predator has an online page for the Cordero Mine, with claims that baseline studies in the late 2000s found gold and gallium at the site. The company didn’t respond to a request seeking comment, but its website says the Cordero Mine is available for lease or purchase, suggesting the polluted site could be opened once again.

With prospectors descending on the McDermitt Caldera for lithium, it seems certain that more mining is in the town’s future.

Alongside many of Nevada’s tribes and environmental groups, Kemp has been vocally against both the Thacker Pass lithium mine and more exploration from an Australian company called Jindalee Lithium. Thacker Pass will complete its first phase of construction in late 2027, the company said.

More visitors mean more business for the rock shop. But at what cost, Kemp wonders.

“There aren’t a whole lot of us here, and I think we get a little bit blindsided by a big company coming in,” Kemp said. “It is a mining town, but I don’t know what its future is. It may be a very big town, but will it be a safe town? That’s what we worry about.”

This series was made possible, in part, by a grant and fellowship from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.