Rural Nevada football team scores on the field of life

McDERMITT — Every so often, football coach Richard Egan encounters a rare teaching moment to help shape his teenage players into more than just better athletes, but better young men.

One such moment came last year when he brought his team to Eureka to play the hometown Vandals in their lush new stadium in central Nevada, a gleaming sports temple complete with a state-of-the-art weight room, field lighting and synthetic playing surface — all built by local mining money.

The McDermitt Bulldogs hail from a tiny town that straddles the Nevada-Oregon border. The team’s school, McDermitt Combined School has 200 students in kindergarten through 12th grade. Most are Native Americans from the nearby Paiute Shoshone reservation.

The lonely high-desert outpost bears its American Indian heritage with pride, but economic opportunities are few and far between in this town where the last working mine gave out decades ago — a place bereft of wealthy benefactors.

In Eureka, the Bulldogs stepped off a less-than-reliable yellow school bus pressed into service for the 12-hour round-trip drive. By late fall, its faulty heater turns the old vehicle into a mobile ice box, forcing players to huddle under blankets to keep warm. For their part, the Vandals are whisked to away games in the comfort of a sophisticated tour bus with their team insignia emblazoned on the side.

That day, the McDermitt boys marveled at a far more privileged world than the one they knew back home. At home, the state line runs through the school grounds, and its football field technically lies in Oregon, amid an isolated spread of dirt and sagebrush. A band of domestic horses grazes in the distance.

Folks around McDermitt are used to hardship. Originally named Dugout, the unincorporated town of 500 residents was established in the late 1800s to protect the stagecoach route from Virginia City to the Idaho territory. Even today, most everything here speaks to what remains of the stubborn and untended rustic American West.

The school’s $60,000 annual sports budget is nearly consumed by $38,000 in fees to bus players from all sports to distant away games, not to mention $12,000 for referees, leaving only $10,000 for everything else. So the football players make do with mostly hand-me-down equipment, with shoulder pads and tackling equipment donated by other schools. They only got new game uniforms two years ago because of an unexpected donation by a foundation run by the NFL’s Washington Redskins.

The school’s bleachers are decrepit. For years, there was little money to provide on-field services until the shop class built a humble restroom. This summer, locusts descended, turning the grass brown, forcing officials to work overtime to green up the field before the start of football season.

The McDermitt kids know few luxuries compared with players in places like Eureka. For them, playing a Friday night home game under the lights remains as unimaginable as an unbeaten season.

Once the ‘heavy hitters’

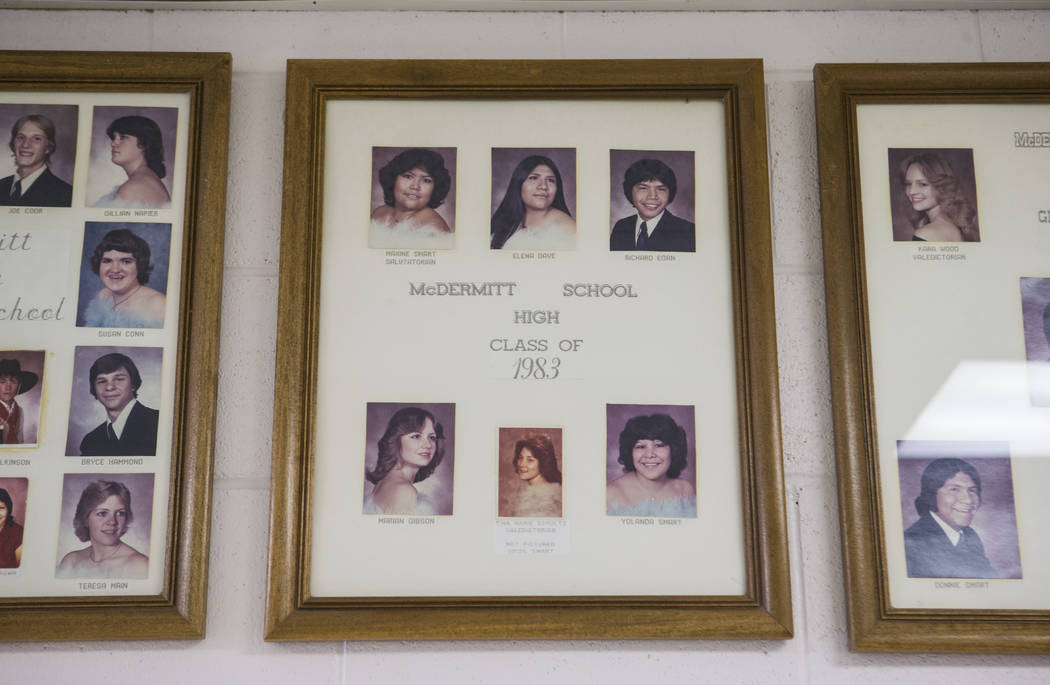

That’s where Egan stepped in. At 53, he’s a Paiute Shoshone who stands 6-foot-1, sporting the big-man athletic build of a one-time ranch cowboy. He played on McDermitt’s undefeated 1982 team that won the state championship.

Back then, the Bulldogs were known as the “heavy hitters,” and players spoke their native Paiute on the field to confuse opponents. Egan played quarterback, tight-end, running back, even kicker — anything it took to win.

Decades later, in addition to his job as the school’s groundskeeper, he coaches a team that resides among the cellar dwellers in Division 1A, the state’s smallest league, where a handful of rural schools field only eight players a game rather than the traditional 11, and their season is a short six contests.

Many years, the Bulldogs fail to win a single game. This season, they’re ranked at the very bottom of the 22-team league. With one game to go next Saturday, their record stands at 0-5, including one forfeit because the team didn’t have enough players. They had been outscored 282-87, including an away-game 78-0 drubbing. Every Bulldog touchdown is celebrated like it’s Christmas morning.

The losses don’t come from a lack of trying. Each year, the tiny school struggles to field even a diminished team. In 2013, the Bulldogs canceled their season because they lacked enough players. This summer, a new principal gave Egan a four-week deadline to find enough kids to avoid yet another lost campaign.

He eventually assembled nine boys: two freshman, a sophomore, two juniors and four seniors, but one senior and a sophomore are first-time players. There are two white kids, two Latinos and a Pacific Islander joining four Native Americans.

Long after his playing days, Egan — a grandfather of three — remains a proud Bulldog. That day in Eureka, he simply would not stand to see his team’s heart broken by another kid’s birthright. Under Egan’s watch, there would be no more damage to these teenagers’ fragile egos. And so he rallied them together, like a coach and like a father.

Nothing rah-rah, just humble encouragement.

“Sure, these kids are lucky to have everything they have here,” he said of the Vandals. “But they can only put eight players on that field, just like us. So once we step off that bus, we represent our community, our school and our families. But mostly, we represent ourselves.”

The Bulldogs lost that day 64-12. Egan said they still came out winners.

Fielding a team

The decision was final: Either Coach Egan fielded at least eight football players by Labor Day or his season was over. “We have other teams relying on us,” principal Leslie Molina said. “We can’t just cancel game after game. It’s not right.”

The previous spring, Egan had considered quitting — after too many seasons waiting for enough players to show up to even hold a practice. Then three cousins promised to play in the fall. That August, a few boys appeared but not enough to field a squad. One kid, a 320-pound player who would have finally given the Bulldogs’ anemic front line a solid anchor, quit after just a few practices.

Two weeks before the deadline, the Bulldogs canceled a scrimmage against a nearby team because they didn’t have enough players. “Both Richard and I sat here grinding our teeth,” assistant football coach Jack Smith said. “We both had great high school careers. We’re competitive people. But it’s tough to be competitive when you can’t even field a team.”

So Egan went to work, just as he’s done in the past. One year, he and his son raffled off a 42-inch flat-screen TV on the reservation to raise money to help fund the basketball team.

The coach called players at home, stopped them in the hallways. Many said they didn’t have the energy to play football. “I did approach kids a few times, maybe too many times,” he said. “Some gave me the cold shoulder. So I left them alone. I knew that if they wanted to play, they’d come.”

Transportation has always been a big problem. Some students live hours from the school, and their parents lack both the time and money to pick them up after practice. So coaches have volunteered to drive them home.

Finally, Egan got some good news: Several players from the distant Kings River Valley finished their seasonal after-school farm chores and were ready to join the team. A few other walk-ons brought his team up to nine players.

The 2018 football season was on.

The school’s dramatic efforts resonate with Humboldt County School Superintendent Dave Jensen. “Even if these kids aren’t winning games, they experience a camaraderie that transcends ethnic backgrounds,” he said. “They’re relying on each other.”

None of it would happen without Egan.

“The only reason we still have a football team is because of Richard,” said Tildon Smart, the Paiute Shoshone tribal chairman. “It’s tough to coach with just eight kids, but he has the passion to hold everything and everyone together.”

Despite the odds

Three plays into the Bulldog’s second game, running back Ben Draunidalo, one of the team’s best players, badly sprained an ankle and hobbled back to the huddle. Egan called over his freshmen and said it was time they started playing like seniors.

Draunidalo stayed in the game. “It wouldn’t have been fair for me to get hurt and not be able to help these guys,” he said.

Win or lose — and mostly lose — the Bulldogs stick together, despite the odds.

On a recent afternoon, they practiced on their home field, performing drills on a donated, taped-up tackling sled. It’s just another way Egan and his team work with what they have. Without a junior varsity program, the kids never learn the basics until they’re on the varsity team. Without enough players to scrimmage among themselves, their tackling skills need work.

At 16, quarterback Jagger Hinkey, a 16-year-old who weighs 205 pounds, gets frustrated in many games. “We’re too small,” he said of a line with a 225-pound top weight. “As soon as the ball is snapped, the opposing linemen are on top of me.”

Last year, even after suffering an ACL tear, Hinkey showed up at games and stood on the field to convince the referees the team had enough players to compete.

And he protects his smaller guys, especially Daniel Gomez, a 15-year-old freshman who stands 5-foot-3 and weighs 93 pounds. Gomez wouldn’t make most teams, but remains an integral part of the Bulldogs.

In one game this year, a 280-pound lineman from an opposing team lifted the tiny Gomez in the air and slammed him to the ground. The freshman popped back up and went on to score two touchdowns in the loss. After the play, Hinkey was in the big man’s face, defending his little scoring threat.

At practice, Egan patted Gomez on the top of his helmet. “He’s got a really big heart for such a little kid,” he said.

Still, Egan has to teach them everything. Leave that sweaty uniform in your locker on a Saturday afternoon, he preaches, and it’ll smell ripe by Monday morning. And there’s no such thing as any three-strikes disciplinary rule. If a player pulls a “no-call, no-show” for practice, he’s allowed back, because the team can’t go on without him.

Following the 78-0 loss, Egan gathered his team at midfield and spoke solemnly, like he always does, reminding them to keep their heads up, their pride intact.

Sometimes, though, the Bulldogs surprise even themselves. In their opening game against Pyramid Lake, they led 38-20 at halftime. Egan warned them about getting cocky; there was still another half to be played. They eventually lost 58-38.

Lasting memories

Even if they lose every game, these kids will never forget playing with the Bulldogs, just like their coach never has. “Thirty years from now, they’ll tell their grandkids what they did,” Egan said. “They’re making memories they’ll keep the rest of their lives.”

On a recent day, the coach walked across the school’s dusty, weed-strewn former playing field, the place where he spent his glory days, when the fans lined up to watch their Bulldogs win a state championship.

Even if his young Bulldogs can never follow in his footsteps, Egan dreams of seeing them savor what he considers the very pinnacle of high school football.

Playing at home on a frenetic Friday night. Under the lights.

“Just to see the looks on their faces,” he said. “Imagine that.”

John M. Glionna is a former staff writer for the Los Angeles Times.