Spending bill keeps government running for now

WASHINGTON -- House and Senate leaders on Tuesday bought themselves a little more time in their efforts to avoid a government shutdown, agreeing to a two-week funding extension that also includes $4 billion in spending cuts.

The deal, which eliminates dozens of earmarks and a handful of little-known programs that President Barack Obama has identified as unnecessary, sailed through the House on a 335-91 vote.

The three House members from Nevada voted for the bill.

"As I've said all along, my goal is to control spending, not shut down the government," Republican Rep. Joe Heck said.

Republican Rep. Dean Heller said the stopgap bill will buy time for Congress to negotiate spending cuts for the remainder of the 2011 fiscal year.

"Ignoring our nation's looming debt is no longer an option for Congress," Heller said. "It is my hope the Senate approves this measure quickly so we can address long-term government spending."

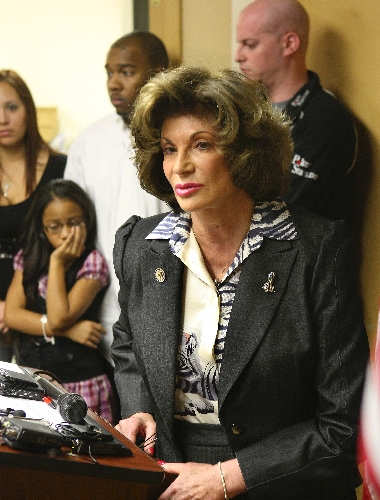

Democratic Rep. Shelley Berkley said the short-term solution "will keep the federal government open and working to serve the people of Nevada and our nation."

But for the long term, Berkley called on Republicans to conduct serious talks on a spending compromise that could avoid a shutdown altogether this year.

"My hope is that we'll see real negotiations replace the 'take it or leave it' attitude that has been on display," she said.

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., who initially resisted including any cuts in a short-term funding extension, predicted that it will pass that chamber as early as today.

Obama also got involved, after largely staying on the sidelines. He placed a 10-minute call to House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, to discuss the temporary spending bill.

If the Senate approves the measure, the two parties will have until March 18 before the government runs out of money. Both parties know there is a limit to the short-term reprieves they can come up with, however. Ultimately, they must find common ground on a longer-term spending plan that will keep the government in business through the end of the fiscal year, on Sept. 30.

The House passed a measure last month that would reduce spending by $61 billion over the seven months left in this fiscal year. The Democrats who control the Senate say those cuts are far too steep and would endanger both the economic recovery and a host of vital programs. Obama has said he would veto the bill.

The scramble to pass the two-week extension underscored a reality that belies the bellicose talk surrounding the prospect of a shutdown: Leaders of both parties are desperate to avoid one, in no small part because they recognize that both sides would probably come out losers.

This would not be an exact reprise of the back-to-back shutdowns of 1995 and 1996, which saw parks and monuments closed, veterans benefits stopped, passport offices shuttered and hundreds of thousands of federal workers furloughed for a total of 26 days.

Republicans bore the brunt of the blame that time. A Washington Post poll released this week suggested that this time, voters would apportion fault about equally to both parties.

What has changed? The state of the economy is far more precarious than it was in the mid-1990s, the deficit is 10 times as large, and the public's confidence in elected officials is even lower.

Both sides recognize that they are not on particularly strong political footing.

Republicans, who only recently returned to power in the House, understand that their mandate is fragile and that it is not time to bring the roof down.

"The American people's priorities are clear," said Boehner spokesman Michael Steel. "They want to keep the government open, and they want to cut spending."

Congressional Democrats have their own challenges. Unlike in 1995, they have control of the Senate. That gives them more leverage to hold the GOP in check and assert their own priorities, but it also means that they cannot escape blame for any impasse.

Another difference: Obama, who has overseen an expansion in spending, does not have the fiscal credibility that helped give President Bill Clinton the winning political hand in 1995 and 1996. Clinton invested significant political capital in reducing the deficit, first by passing his 1993 economic package, which included tax increases, and then, in 1995, by putting forward a 10-year plan to balance the budget.

Nor does Obama have in Boehner the kind of polarizing foil that Clinton had in then-Speaker Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., who at one point suggested that he dug in on budget negotiations because Clinton had snubbed him aboard Air Force One.

But if the politics of a shutdown are in many ways more treacherous than they were in 1995, the actual effects of one would probably be less disruptive. Indeed, so many things have now been declared essential services that the government might "shut down" without most Americans noticing much difference.

As happened in 1995, air traffic controllers would still watch the skies. And a wider swath of military, diplomatic and national security personnel would stay on the job to deal with concerns in a post-9/11 world. These would include screeners for the Transportation Security Administration, created since the last shutdown to patrol airport security checkpoints, and more civilians at the departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs.

Also likely to stay open are new Treasury offices dealing with economic recovery and financial oversight.

The automation of most government benefits means beneficiaries would still probably receive payments, though thousands of Social Security or VA employees would be needed to process them.

Even at reduced levels of operation, tens of thousands of contractors employed by military and civilian agencies -- especially those providing building security and technical support for the government's websites, e-mail systems and databases -- would probably keep working to ensure continuity of operations.

Therein lies the paradox under all the talk of a shutdown. Privately, some Democrats say they fear that a closure that barely affects the daily lives of most Americans could bolster conservatives' argument that much of what the government does is unnecessary.

But there is one area where a shutdown would have greater consequences this time: Federal spending on contracting has ballooned from a few billion dollars in 1995 to $535 billion last year.

Small and mid-size firms relying on government work to survive -- the same small businesses the Obama administration hopes to protect with its economic recovery plans -- have no guarantee that Congress would reimburse them for time lost.

No retroactive pay means hundreds of thousands of contractors could go weeks without a paycheck. (Lawmakers and Obama could fall into that group too, under a measure approved Tuesday by the Senate.)

Stephens Washington Bureau Chief Steve Tetreault contributed to this report. Staff writer Felicia Sonmez contributed to this report.