7 DAYS TO FRIDAY NIGHT

Chris Faircloth appears calm, maybe for the first time all week.

He walks the sideline, more strolling than stalking. He purses his lips and exhales, purses his lips, exhales. His face, expressionless. His eyes, steady. His mind, racing.

The Las Vegas High head coach is thinking about only one thing: QB7.

James Cammack, Rancho High's quarterback -- QB7, the LV coaches call him -- is about to call for the snap on a beautiful Friday night at Frank Nails Field. Sir Herkimer's Bone is up for grabs, as is a guaranteed spot in the Sunrise Regional playoffs. Hard to tell which means more.

Faircloth has good reason to worry about QB7. The kid has a cannon for an arm. He pumps and fires, and the ball sails through the air on a zip line, not so much deftly finding a receiver's hands as breaking his fingers.

But when the pocket collapses, when QB7 faces pressure, that's when he's really special.

QB7 will step into the pocket and back out quicker than a defensive lineman can get out of his stance. He'll turn a pass play into a ballet recital, pirouette his way into the open field, select a target and let it fly.

With this quarterback, anything can happen.

Yeah, it's fair to say that while Faircloth appears calm on the outside, inside his stomach is churning.

"He's one of those kids who can change an entire football team," Faircloth says earlier in the week. "He's one of those kids who can just wreck your Friday night. Somewhere, you're going to have some kind of answer for him."

At this point, it's still early in the Bone Game -- a rivalry contest between Las Vegas High and Rancho that is in its 50th year -- and neither team has found much rhythm on offense. It's too soon to tell if QB7 is having the impact the Wildcats coaches expected. But that can change at any second.

The center snaps the ball, and Faircloth's focus is on one thing and one thing only: stopping QB7.

Except Faircloth is not really there. Sure, he's on the sidelines, his bald head glistening under the lights, but he's not there.

The thoughts of the Las Vegas High football coach, the 2006 Nevada Coach of the Year, the coach of the two-time defending state champion Wildcats, have drifted back to six days earlier in his coach's office. In his mind, it's Saturday morning, when the real game starts.

[SATURDAY]

"THE EVALUATION OF FRIDAY NIGHT AND INTRODUCTION TO NEXT WEEK'S OPPONENT"

Take the most famous football coaches in history: Knute Rockne, Vince Lombardi, Paul Brown, Bill Parcells. Roll them into one man, shave his head and toss on a pair of dimples.

You've got Chris Faircloth.

Thick like a linebacker with a few extra years and a few extra post-game hot dogs, the 50-year-old Faircloth is very much a football coach.

If he could only teach football, he would, though he enjoys his weightlifting class at Las Vegas High School. If he could only breathe football, he would, if not for that pesky oxygen. If he could drink football -- toss a ball in a blender and mix it with one of his daily doses (try four or so) of Red Bulls -- he would.

Sure, such coaching comparisons might seem hyperbole, a bit of grandeur about a regular coach and a regular program. But this isn't a regular coach, and this isn't a regular program.

Three state titles in six years. Five state title game appearances in six years. A 44-9 record in three full seasons under Faircloth. A coaching staff that Faircloth says is "obsessed with the damn thing."

The team moms look like models and the locker room is made of pure gold.

Things around East Sahara Avenue and Tree Line Road are pretty good right about now.

Well, actually, they were good until a few weeks ago, when the Wildcats lost to Sunrise Region rival Valley High. They were good until Faircloth popped in game film this Saturday morning of the previous week's game between Rancho and Canyon Springs.

Know two things about Faircloth: He absolutely, positively, pain-in-the-pit-of-his-stomach, oh-no-I'm-going-to-vomit hates losing.

And, he's a man of few words.

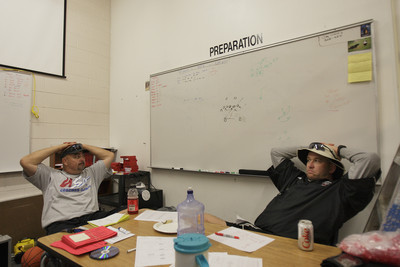

Sitting in his office, surrounded by several members of his highly committed, should-be-committed staff, Faircloth watches Rancho's QB7 for the first time.

QB7 this way and QB7 that way. Up the field, down the field, around the field. Throwing, running; running, throwing.

"That QB7 is lightning," Faircloth says, resigned to the fact that the entire week that lies ahead will be devoted to stopping him.

But lightning only strikes somewhere once. QB7 keeps nailing Canyon Springs the same place, over and over, directly around the right corner.

Faircloth and his staff will spend the afternoon devising a plan to stop him.

It won't be a particularly fun assignment, but it's necessary.

Faircloth is in a somber mood.

Earlier this day, after the team gathers to watch game film of the previous night's 28-14 victory over Chaparral, after a trip to the basketball gym for some "warball" -- think ultimate, no-holds-barred dodgeball -- Faircloth will attend the funeral of one of his former players, Troy Flowers, a 1997 Las Vegas High graduate who recently died of cancer.

"I don't really deal well with death anyway," says Faircloth, whose mother passed away last summer, following his father and two brothers. "Going to a funeral, you don't know how you're gonna be emotionally. There's times I'll be brought to tears just talking about it. It's hard because he was a great kid, too. And you get 200 or whatever kids coming through the program every year, and you get to know them on a personal level."

All football teams are families. All sports teams, period, really. Players are your brothers; coaches are your fathers.

At Las Vegas High, family means everything.

"In a lot of ways, you help raise somebody else's kid," Faircloth says. "We have some kids who come from great families, and we have some kids who come from the opposite. You may have to help them financially -- whatever it takes to help them out. We're just to a point where we just do it. They're like our own kids. They need money to go to prom? Myself or another coach might toss them $50 or $100.

"They're like our own; they really are."

Except for one thing.

During the season, when weekends are devoted to game film and the rest of the week is devoted to practice, Faircloth will see much more of his sons on the team than his son at home.

[SUNDAY]

"WHEN WE LEAVE THIS DAY, WE TRY TO GET EVERYBODY ON THE SAME PAGE"

Nine children sit huddled, Indian-style, mouths ajar, paper flying everywhere.

Grant Faircloth's sixth "boooo-thday" party -- Halloween is right around the corner -- is a rousing success. Then again, what sixth birthday party isn't?

The kids have come to King Putt for the miniature golf, but that idea went by the wayside quickly.

"Whooooooa."

The voices rise an octave a second, the way kid's voices do when they're excited. They have the right to be. Grant is tearing away at his birthday presents, and he's just unveiled a dinosaur.

With Grant seated next to her, Joy Faircloth hurries to the next present. If a first name could tell an entire story, Joy's would.

Chris and the then-Joy Polly met 14 years ago at Las Vegas High, where both were teachers. After a short courtship and two years of dating, they married in 1995.

"This is another good one," Joy says, laughing. "For our first date, he took me out to watch 'Monday Night Football.'"

Grant came along in 2001, and here he is, shredding more Rugrats wrapping paper, unveiling a Railroad Rush Hour puzzle. Grant is ecstatic. The other kids are thrilled. The other parents are smiling.

All but one.

Away from the huddle, Coach Faircloth sits, his eyes glazed over, vacant. He's there, but, then again, he's not.

For Faircloth, it's already Friday night. QB7 is dancing in the backfield, evading the Wildcats' pressure.

"You can see it on his face," Joy says. "I know that he's not listening to me. He's just got that look, that gaze. He'll say, 'Oh, yeah, honey, I heard you.' Yeah, right. There's that football-season look."

This is not an unnatural phenomenon among the Las Vegas coaching staff. Faircloth imagines that of a possible 168 hours per week, he's thinking of Friday at least 140 of them. His staff, too.

"We'll usually go to church on Sunday mornings, and I'll sit in church and they're doing the gospels and the whole flippin' deal and I am there in body only," Faircloth says. "I'm not even sure what happens in church when we go. During the season, I'm out there. I'm lost."

Sometimes, 140 hours isn't enough. He doesn't often dream of scrambling quarterbacks, but when he has too much on his mind, it's not a peaceful sleep.

"If you're really stressing a situation, you will have very stressful dreams," Faircloth says. "It's like you wake up and you're glad to be awake again. Whatever I'm doing now is better than what I was doing in that dream.

"And then, in the offseason, it's never like that. It's like somebody turns off the switch."

He'll snap out of the gaze eventually. He's back at Grant's birthday party, chatting with parents.

Inevitably, the Valley game gets brought up: "Yeah, we should've won that game," he'll tell a mother, and he'll eat cake and enjoy some time with Grant.

But he knows it's right back to the coach's office, to pore over more game film and to come up with a flex defense that might stop QB7 on Friday night.

The party is about to wrap up, and Faircloth sees the perfect time to sneak out. He tells Joy he's leaving and gives her a kiss, then spots Grant sitting on a motorcycle video game and gives him a hug, telling him he has to go to work and he wishes he could be there longer.

As he walks out the door, Grant blows him a kiss.

Coach Faircloth doesn't see it.

[MONDAY]

"THE MOST PHYSICALLY CHALLENGING DAY OF THE WEEK"

A program doesn't go from perennially poor to perennially average to perennially successful without making a few changes.

Ask anybody on the Las Vegas coaching staff, and it started with the hiring of now-UNLV wide receivers coach Kris Cinkovich in 1995. Coach Cink didn't reinvent the wheel or introduce the forward pass, but he installed two things that have remained ingrained in the deepest recesses of each coach's mind.

The first: Losing is not an option.

Coach Faircloth cannot imagine what it would be like to miss the playoffs, which is a very real possibility entering the Rancho game.

"It is absolutely terrifying," he says. "For all the work that our coaches and kids put in, it would be a travesty. It would take us forever to get over. Trust me, (I) would consider resigning if it didn't work out. That's how important that is. I'm being very honest. That'd be very hard to handle. Not getting there? I don't know. It'd be an absolute waste of time."

The second: An increased dedication in the weight room, specifically to the Olympic lifts, is demanded.

It's Monday morning, and coach is standing in his classroom. There are no calculators or computers. You won't find a single book or even one dry-erase marker.

Instead, you'll find 45-pound weights stacked on top of each other and a 17-year-old kid trying to thrust them over his head in a single move. When he's done with the exercise, he'll get pats on the back from his classmates, a fist bump and a feeling of pain mixed with relief. Then he'll check himself out in the mirror.

Faircloth's classroom is the weight room, where bad attitudes go to die and muscles go to be defined. Every day for hours on end, coach teaches kids how to improve their core. Every football player takes the class, but nonathletes are enrolled, too. Some kids are as thin as the bar they're trying to bench press.

But it works.

The students are disciplined and committed, almost fanatical about impressing their teacher, their classmates, themselves.

And it translates on the football field for some.

"It's all about what coach Faircloth does in the weight room," says assistant coach Mike Grayjek, who handles Wildcat wideouts. "Size-by-size, athlete-by-athlete, Canyon Springs has got better athletes. They got better size. But I don't think anybody in this town or in the state that I've seen yet, is working harder than we're working in the weight room. It's what happens in the weight room, in the offseason that brings us success Friday night."

More specifically, it's the power cleans.

When Coach Cink left for UNLV in 2004, bequeathing the program to Faircloth, the new head coach knew he had some work ahead. Faircloth traveled to West Monroe, La., to study coach Don Shows' powerful Rebels team, which won unofficial national high school championships in 1998 and 2000.

Faircloth took from the visit a rededication to the power clean, an exercise designed unlike most other lifts.

A bench press focuses on the chest, arms and back. A squat: the legs, stomach and back. An arm curl: the bicep and the triceps.

But a successful clean works several muscles in unison, requiring an initial burst, balance and strength. Most of all, it requires an inner spirit, a will to push oneself past the barrier of "can't."

The row of trophies in the weight room is a testament.

They are big and short, made of plastic or wood, miniature golden athletes affixed to the top. There are dozens of trophies, each bigger than the next.

The best of all: the massive award for 2007 National Power Clean Champion.

But that was last year, and this is now. Faircloth's goal, the program's goal, is 40 players power-cleaning more than 225 pounds. The state championship team from 2006 had 42 players. So far this season, just 24.

How things can change.

And Faircloth knows that.

Sitting at his desk, with Las Vegas carved in the side of wood, Faircloth concedes that this year's Wildcats are just not as experienced, not as talented, as his past two teams.

Not that he'd give it up. Not that this season hasn't been worth it. Not in a long shot.

"Yeah, it'd be worth it," Faircloth says. "We coach football because we love football. Now if we were going 1-8, 1-8, 1-8, then I think we'd have to re-evaluate. God, I hope we don't end up in that situation, but it could happen. We're not used to being in that situation, which would even make it harder. We have an accustomed lifestyle, we like to think around here, where if you're willing to outwork (the opponent) and you get everyone buying in, then your results should be different than everybody else's.

"Would it be worth it? No, it wouldn't be worth it. Would we stop doing it? No, we wouldn't stop doing it. I have to do this. We have to do this."

[TUESDAY]

"ON TUESDAY, THEY NEED TO BE FAMILIAR WITH WHAT WE'VE ASKED OF THEM"

In some ways, Faircloth is a double agent, leading two distinct lives.

Faircloth as coach: demanding, obsessive, high-impact, angry.

Faircloth as father: patient, tender, relaxed, softer than a koala, which he resembles with his deep dimples.

The dichotomy between Faircloth as coach and Faircloth as father is striking; it's even hard to decipher which comes more naturally to him. On the field, in the midst of chaos, he's in his habitat. At the dinner table, in the midst of calm, he seems equally as comfortable.

Rarely do the two worlds collide.

But on a day like Tuesday, it's hard not to bring work home. The Wildcats slogged their way through practice, going through the motions, frustrating their coach.

After the crushing loss to Valley two weeks ago, Faircloth views any sloppy practice as a personal affront. His head shaking, his jaw rapidly clenching and unclenching, Faircloth paces the field, frustrated.

He'll be thinking about practice all night.

"I certainly didn't bargain for the way it turned out," Faircloth says. "I certainly kind of figured that it was all going to work out, and there'd be balance. Obviously, there's never been balance in my life. I'm probably still not very good at putting things in the right perspective. You should always be father first, coach second. I'm having a very difficult time with that.

"I have a 6-year-old little boy. That's skewed. I'm skewed. It's always coach first."

When his two lives do collide -- Faircloth as coach, Faircloth as father -- it's a sight to behold.

In his home in Henderson, which overlooks Legacy golf course, there are only two kinds of books. There are the coaching manuals/ motivational titles: the "Lombardi and Me," the "Quiet Strength," the "Quotable Coach." And there are the children's books: the coloring books, the books about dinosaurs.

A desk holds two prominent items: the family computer and the acrylic plaque from his last senior class, inscribed with the words "Back-to-Back State Champs." On the desk is a Vince Lombardi poster detailing the steps to success. The words at the top of the poster are in italics: "You've got to pay the price."

Laying on the poster is Grant's "Fun by Numbers."

Faircloth as coach, Faircloth as father.

"As much as my family means to me, obviously they suffer because of my other commitment," Faircloth says. "But her No. 1 commitment is to our child. If she wasn't such a good mother with our son, I'd have to scale back what I did. I'd have to be a JV football coach or something."

In the family household, duties are divided quite simply. Joy gets most -- OK, all -- of the chores, the responsibility of running the home. Coach Faircloth gets the more tender moments, helping Grant brush his teeth and floss, putting him in the bath, tucking him in at night.

As a group, they share three things for which they are thankful each day, before a family prayer.

Grant prays for the simple things, as a little boy should. A friend's impending birthday party highlights his list. Joy says she's thankful for her morning workout.

"I'm thankful for getting a good start to the morning, getting to school early," Coach Faircloth says, kneeling beside his family. "I'm thankful for being able to come home and spend time with Grant.

"And I'm thankful we get to look forward to practice tomorrow, because we were so bad today."

Faircloth as coach.

[WEDNESDAY]

"THE NEED TO EXECUTE AT GAME-SPEED WHAT WE PLAN TO DO ON FRIDAY"

It's hard not to miss Wednesday night practices.

Game days are fun, the culmination of a week's worth of hard work, the end result of the blood and the sweat and the tears. But there's something special about Wednesday nights.

Monday and Tuesday practices are devoted to routine, to picking up the system and nailing down assignments. Wednesdays are a whole different monster. Regularly held at night, under the lights, there is energy in the air.

Players hit with a sense of urgency not felt during the previous two days. There's a hop in each of their steps, a bounce in their gaits that oozes pure joy.

Even Faircloth is more intense.

More intense? This is a guy who snorts Copenhagen tobacco. Literally sniffs snuff.

No wonder he's bald. All the hair is on his chest.

Today, he pounds the ground with each step, angry at the world that it just isn't Friday night already, dammit.

He mans his station, a group of linebackers, where he joins assistant coach Brad Talich in teaching proper technique and which gap to fill. A former college linebacker, Faircloth puts added attention on the linebackers. In this week's defensive scheme, the flex, the importance of gap control is paramount. If a linebacker misses his assignment, QB7 might break to the outside, running to daylight.

The combined efforts of Faircloth and Talich, a defensive wizard with 18 years of coaching experience and head coaching offers, has worked best with starting middle linebacker Colin Shumate. If anyone on this team embodies what it means to be a Wildcat, it's Shumate. He's a quiet team captain, often leading by example, which usually equals about a dozen tackles.

And it's only his second year playing linebacker.

"It was a pretty big learning curve. The year before, I played offensive tackle; the year before, tight end," says Shumate, who's being courted by several Mountain West Conference schools, among others. "I knew I had to catch on quick. But coach just made it simple. Working with him, it became natural.

"I credit everything that has happened the past four years to these coaches. There's potential in anyone who can go to the next level, but they brought it out of me."

After working in individual groups, the players grab some water and hurry back for special teams practice. Then it's back to individual groups, some more special teams, and some more individual groups.

The defensive linemen focus on the rip technique with coach James Thurman; the offensive hogs work on the drop step and hand placement with coach Art Plunkett. Coach James Sawyers challenges the defensive backs with a deep pass, forcing them to imagine QB7 lofting one into the end zone; former star quarterback O'Ryan Bradley (now grayshirting at UNLV) tutors heir apparent Marvin Campbell in the five-step drop. Assistant coach Grayjek keeps it light with his wideouts, making them laugh and then telling them to quiet down. Offensive coordinator Zach Ordish schools running backs Robert Hackett and Emery Schexnayder on pass-blocking techniques.

And Faircloth oversees it all, bouncing from one group to the next.

This is not normal. At most high school football practices, it's group drills for 30 minutes, team drills for 45, group drills for another 30 minutes and a team scrimmage for an hour. Practices can typically take up to three hours, leaving the kids battered, bruised and exhausted.

Not at Las Vegas High.

Wildcat practices last around two hours on most days, and the practices are split into 6-to-10 minute intervals, leaving players crisp and attentive.

"Times change; things evolve," says Plunkett, a former NFL offensive lineman with the St. Louis Cardinals and New England Patriots and a longtime Las Vegas coach and current athletic director. "When I played high school football, water breaks were unheard of. Even in college, they were unheard of. It's, 'Eat some salt tablets, drink some water, eat some salt tablets and get out to practice.' But we take care of our guys. It's more than just beating the crap out of them to get a good athlete. You got the weight room, food, nutrition, agilities. We do everything. We want to build an all-around athlete, compared to just some guy who can beat the crap out of somebody else."

[THURSDAY]

"REVIEW, PREPARATION, MOTIVATION"

Monday and Tuesday, mental. Wednesday, physical. Thursday, spiritual.

By the end of the week, the Wildcat coaching staff has just about done all it can. The assignments are tattooed on a player's brain, the responsibility with 36 hours to kickoff now on the players' shoulders.

The team goes through simple walkthroughs on Thursday morning, just nailing down the basics. School was a blur, the time mostly occupied by discussions about corsages and limos and hairstyles. Friday night is not just a battle for playoff positioning, not just a fight for The Bone, not just a big rivalry between two bitter schools.

It's homecoming.

Sitting at Pressutti's Italian Deli near campus for a pregame meal, the players load up on spaghetti, a massive carbo-load. They laugh and joke, ragging on each other for choosing a cream-colored tuxedo as opposed to the traditional black.

Faircloth stands in the corner, an absent look on his face.

He's eating spaghetti; the stress is eating him.

"Somehow, (eating) satisfies the stress in my system,'' Faircloth says. ''Unfortunately, it probably puts on about 20 pounds and I have to spend the offseason getting it off. The food somehow helps ease the pain of the stress."

It's hard for a coach as involved as Faircloth to relinquish responsibility to his players. You just know that if his knees -- and Joy -- would allow it, he'd be on the field, too.

"It is hard to give up control," Faircloth says. "One of the challenging things about coaching is you want to do it for them. And too many coaches, when things don't go well, it's, 'Kids, kids, kids; those damn kids.' That's your job as coaches: to get the kids doing what you want to get done. That's been a problem this year. We have some kids who are round pegs in square holes."

For the Rancho matchup, though, it might be too late to make a perfect fit. Now all he can do is motivate his players, get them as fired up as possible.

After the meal, the players return to campus for motivationals, where coaches will hand out "Catpaws" -- helmet stickers awarded for spectacular plays -- to deserving players. Then it's time for highlight films of the previous week and of older Bone games.

Next, in a practice that just started the previous week, Faircloth calls seniors, one by one, to the front of the room. Their job is simple: "What does it mean to be a Wildcat?"

For each it means something different. Wide receiver Michael Alexander talks about the team as family. Defensive back Jonathon Dugan places emphasis on the hard work it takes to play for Las Vegas High and the payoff at the end. Defensive lineman Ben Moser discusses the importance of the Bone Game, and the ribbing he'd gotten all week from co-workers who are Rancho fans.

"I expect us to go out there tomorrow and give it our all," he says. "And I want to beat their ass tomorrow, go into work and say, 'Who's talking now?'"

[FRIDAY]

"THE ACCUMULATION OF A YEAR'S WORK"

Game day.

The tension builds throughout the day, and it will not cease until around 8:30 p.m., when the final seconds tick off the game clock.

Faircloth will be nervous all day: through the morning quick ladder drills, through hours of weight training, through the pregame walkthrough, through the motivational speech that you swear couldn't be better if Lombardi gave it himself.

The players will be equally strained.

When they break off in the wrestling room for a players-only meeting, they try to be calm, try to relax. They lay on the mats, perhaps dozing off. But they can't force the game from their minds.

"Big night, fellas," Shumate says as his teammates gather in front of him, looking upon the senior leader as if he's Moses carrying a pair of tablets. "We lose this we're out."

A lot is on the line during the next couple of hours. The players know it, the coaches know it, the waterboys know it. Just about the only person who doesn't seem to know it is Grant, who seems more interested in the "Birthday Boy" pin affixed to his shirt.

Today is his sixth birthday. It just had to fall on a Friday, didn't it? Just like it did when he was born, when Daddy was in the delivery room.

Today, the family celebrated at 5 a.m. with birthday doughnuts, 30 minutes before Daddy had to leave for school.

Now it's hours later, and the game is about to start. Daddy is decked out in his coaches gear, similar to what he's worn all week -- shorts, sneakers, red or black shirt, black visor that seems glued to his head -- and he's pacing the sidelines.

This must be like how DaVinci felt when he painted the first stroke of the Mona Lisa, how Hendrix felt when he struck the first chord of the ''Star-Spangled Banner'' at Woodstock.

Kicker Trevor Lowe's foot touches the ball, and it's on. The ball skips three times and bounces off a Rancho Ram, into the arms of a Wildcat. Not a bad start.

For the next 48 minutes of game time, stretched across more than two hours, QB7 will dance and spin.

Only he'll dance and spin behind the line of scrimmage, with absolutely zero running room. He'll try to pass, and three Wildcats will greet him with a sneer. He'll try to run, and he'll get stuffed.

The flex defense will work to perfection.

After all that big talk, after all the stress, Las Vegas holds QB7 to 6-of-20 passing for 50 yards, intercepts him twice and allows him 8 yards on nine rushes.

The Wildcats offense struggles early, enraging Faircloth. The offense settles down and finds a rhythm. The running backs, Hackett and Schexnayder, break off a couple of long runs, and Las Vegas heads to halftime ahead.

Not that Faircloth is satisfied.

"I'm not doing very (expletive) well; we should be kicking the (expletive) out of them," a candid Faircloth says at halftime, with his team leading 20-0.

Ultimately, Rancho does nothing on offense and the Wildcats continue to roll.

And after 140 hours of preparation, after so much energy and focus and care and love, it has come down to domination.

Final score: 32-0.

As he walks off the field, Faircloth says he's satisfied with his team's defensive performance, but laments offensive mistakes. He seems at ease.

Then he spots Joy and Grant, smiling and clapping on the sidelines.

He heads straight into Joy's accepting arms, which would've felt the same had the Wildcats lost, and wraps himself in her. He picks up Grant, kisses him on the forehead and asks if he got to touch Sir Herkimer's Bone, before it's put in a glass case for the next 365 days. He says goodbye to two of the three loves of his life -- we all know the other -- and tells Joy he'll see her in the morning.

After all, 15 minutes after the game has ended, he'll join the other coaches in his office.

He has next week's opponent on his mind.

Preps Central

FAIRCLOTH BY THE NUMBERS 2006 - Nevada coach of the year 140 - Hours spent per week during season immersed in football 44 - Victories as LVHS head coach 12 - Former Wildcats now playing in college 6 - Age of son, Grant 4 - Years as head coach at Las Vegas High 2 - State titles Audio Slideshow