Congenital defect leads to brain surgery for 11-year-old

With brain surgery, even the slightest error can result in problems with speech, memory, balance, vision, coordination.

But doctors told David and Carly Held early this year that brain surgery was what their 11-year-old son Nathan needed.

Otherwise, the youngster who had complained of what he called “ice-pick headaches” above his right eye might soon become blind or paralyzed.

Nathan has had five procedures at a cost of more than $500,000 that neurosurgeon Dr. Kelly Schmidt said should allow him to live a normal life. As Nathan sat on a couch in the family’s Henderson home, his exhausted father summed up the past six months.

“It’s been an absolutely horrifying experience for all of us … so many sleepless nights,” he said.

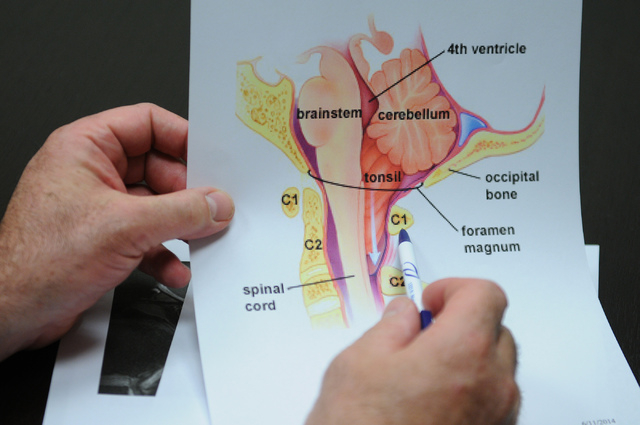

The trigger of the Held family’s barely contained panic is a Type I chiari malformation, a congenital defect in the area of the back of Nathan’s head where the brain and spinal cord connect, and an associated syringomyelia, a hole that often forms in the spinal cord as a result of a chiari malformation.

Neurologists say the condition, prevalent enough in Las Vegas to have inspired the formation of a support group, occurs in about one in every 1,000 births.

Because a Type I chiari malformation frequently interrupts the normal flow of cerebral spinal fluid between the brain and spinal chord, the hole in the spinal cord often fills with fluid, creating a cyst. Should the cyst expand or enlarge, it can cause further spinal cavity compression, resulting in pain, stiffness and muscle weakness.

“It sounded like such a difficult thing to deal with,” Carly Held said as she showed the scar in the back of her son’s head.

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, chiari malformations occur when there’s not enough space in the back part of the brain, forcing it downward. The cerebellum, the part of the brain that controls balance, leaves its normal location within the skull and descends into the upper spinal canal.

That results in the cerebellar tonsils (the lowest part of the cerebellum) being pushed out of the hole in the base of the skull to hang down, where they push against the bottom of the brain stem and the top of the spinal cord. The pressure can affect bodily functions and block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid to and from the brain.

In October, Nathan’s occasional “ice-pick headache” symptoms — neurologists say every chiari malformation is different — struck with more frequency. Doctors would later say the symptoms signaled increased pressure on Nathan’s spinal cord.

But Nathan’s pediatrician thought he had a problem with his eyes and thought it unlikely that the headaches were serious. Still, she arranged an appointment with a neurologist, who also doubted anything was seriously wrong.

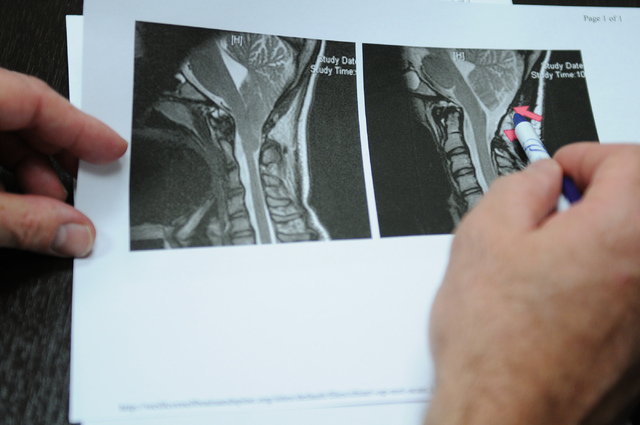

Just to be safe, though, she scheduled the magnetic resonance imaging that would detect his condition.

“I hate to think what would have happened if we didn’t get that MRI or didn’t have insurance,” Carly Held said.

What frequently puzzles doctors is that not everyone with Type I chiari malformations are symptomatic. These people may find out they have a malformation only after undergoing an MRI for another reason and never need treatment.

Many others, including Las Vegans Lori Huckaby, Christine Smith and Amy Schaus-Castano may go decades without being diagnosed because their symptoms, while often debilitating, mimic other conditions, including muscle weakness, numbness in the arms or legs, dizziness, vision problems, difficulty swallowing, ringing in the ears and migraine headaches.

In 2012, the magazine Neurology Now reported how singer Rosanne Cash suffered for 10 years with what were thought to be migraine headaches or Lyme disease before she was diagnosed and surgically treated for a Type 1 formation.

“It’s both underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed,” said Dr. Michael Seiff, a Las Vegas neurosurgeon. “A lot of symptoms you don’t normally associate with a neurological condition. Some people only become symptomatic after a traumatic event.”

Schaus-Castro, 35, said she now realizes she underwent unnecessary jaw surgery.

“A lot of doctors just don’t think of it,” she said. “It isn’t on their radar. I was finally diagnosed in 2009 but all the years that I wasn’t treated for it resulted in permanent damage. I started having severe headaches when I was 11.”

The 42-year-old Smith, a mail carrier, wasn’t diagnosed until 2007.

“I suffered all my life. I had headaches, would pass out, have numbness in my feet, would be paralyzed for short periods of time,” Smith said. “I was treated for everything but chiari, I think.”

The 55-year-old Huckaby, who formed a chiari malformation support group in Las Vegas (call 702-349-6603) following her diagnosis four years ago, said both the public and physicians need to become more aware of chiari malformations.

“One of the problems we’re facing,” she said, “is that doctors aren’t quick to order an MRI. Because of the tingling I had in my hands and feet, doctors thought I had carpal tunnel syndrome.”

Because her diagnosis came decades after her first symptoms, Huckaby lost hearing in one ear. The surgery she had for her condition has helped with headaches and balance problems but it didn’t restore her hearing.

There are four types of chiari malformations, with Type 1 being by far the most common. Type 2 is almost invariably associated with spina bifida, which frequently causes paralysis of the lower limbs and sometimes a mental handicap. Type 3 is extremely rare and associated with life-threatening complications in infancy. Type 4 is usually fatal during infancy.

Chiari malformations are named for Austrian pathologist Hans Chiari, who first identified Types 1-3 in 1891.

No one knows the condition’s exact cause. Researchers say the malformations appear to be caused by a developmental failure of the brain stem and upper spinal cord within a developing fetus. There may be a genetic component.

Those with mild symptoms can be treated with pain relievers. But for someone who has an associated syringomyelia with a severe disabling headache or other debilitating neurological symptoms, surgery becomes the only choice. Most people go home within three or four days, but weeks or months are needed for recovery, depending on severity.

Seiff says what’s known as “decompression surgery” for a chiari malformation, which can take two to four hours, generally follows common steps:

First, the neurosurgeon makes an incision in the back of the head and removes a small piece of skull, which can relieve pressure and give more room for cerebrospinal fluid circulation. In most cases, the surgeon then removes part of the spinal canal’s bony covering to provide even more room for cerebrospinal fluid circulation and to remove scar tissue.

Often, further decompression is necessary, and the dura, the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord, is opened, relieving pressure on the spinal cord. A patch, allowing the dura opening to enlarge, is sutured into place.

Then surgeons cauterize and shrink the cerebellar tonsils that hang onto the spinal cord and cause pressure.

“I’m more aggressive and I think I get better results by actually removing the tonsils,” Seiff said.

Nathan Held’s initial surgery in March at Sunrise Hospital went well.

“He was doing great at home in recovery but then he got sick from scarlet fever and strep throat,” Carly Held said. “I’m so glad there was a support group to help us get through this.”

Strong antibiotics to stamp out those conditions caused Nathan to vomit, an action so strong he blew a hole in the patch Schmidt had sutured over his dura. Nathan began leaking spinal fluid and had terrible headaches. He couldn’t get out of bed.

Schmidt brought Nathan into the hospital in April to patch the patch.

After being sent home, Nathan again seemed on the way to recovery until he gagged, and then vomited, after taking a pill. More spinal fluid leakage followed.

Three more procedures followed in ensuing weeks — it was nearly June before everything was completed — to control his condition.

Schmidt implanted a temporary tube, or shunt, to drain the excessive spinal fluid causing pressure inside Nathan’s head. Later, a permanent tube was surgically inserted and connected to a flexible tube under the skin, where it can drain the excess fluid into the abdominal area for absorption by the body.

Nathan, who spent 12 nights in the intensive care unit besides six nights in a regular room, also received another patch over his dura.

“What happened with him is definitely not something we usually see,” Schmidt said.

As he sat in his chair and played a video game, Nathan sounded weary.

“It’s been a rocky road,” he said. “I’m trying not to get my hopes up too much that this is over. Every time I think it’s over, there is another surprise.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.