Heart transplant recipient works to help others live full lives

Go out and live a normal life.

It is what Dr. John Ham and other transplant physicians around the world tell individuals who are fortunate enough to receive a lifesaving organ.

Yet even Ham, the medical director for both the Nevada Donor Network and University Medical Center’s kidney transplantation program, admits he has a difficult time believing how normally Simon Keith — the 48-year-old chief operating officer of the donor network — has lived his life since he underwent a heart transplant in 1986.

“I marvel at it all the time,” Ham said. “Our goal is to restore normalcy as much as possible. Of course, what he has done, is doing, is amazing. We now know normalcy for transplant patients can mean far more than even we thought.”

Normalcy for Keith was leading the University of Nevada, Las Vegas soccer team to the NCAA tournament in 1987 and 1988, earning all conference honors, becoming the top selection in the Major Indoor Soccer League draft, and then playing professionally just three years after his surgery.

Marriage, fathering three children, starting successful merchandizing businesses, drinking an occasional beer, eating a greasy hamburger or smoking a cigar from time to time, playing hockey and golf with his kids, doing hourlong Ultimate Fighting Championship workouts four times a week — that’s been normal for him, too.

Saying virtually nothing about his heart transplant, even when asked directly about it, has, until fairly recently, also been the norm.

“I always wanted to be a normal guy, not a guy whose life was about being a transplant recipient, treated like he had ‘Fragile, Handle With Care,’ stamped across his forehead,” Keith said recently. “I didn’t want to be pitied, someone living life in a bubble. The transplant wasn’t something I wanted to talk about. I thought doing so was counterproductive to someone going forward. When I was asked about it, I described the procedure as ‘one in, one out.’ I was very casual about it, very matter of fact.”

Now, however, Keith, who asked UNLV staff not to alert the media to his transplant while he was playing for the university, believes he has come to a time in his life where discussing his transplant publicly, and often, makes sense to him.

In other words, he now finds it normal.

Struggle to survive

How Keith got to this time and place is instructive both to those thinking about donating organs and to those hoping and praying they receive them. More than 6,000 Americans die each year, about 18 a day, waiting for an organ. Nearly 117,000 people are on waiting lists.

Today, with Keith a key executive at the donor network, Ham believes the former soccer-player-turned-entrepreneur-turned-nonprofit-business-executive has had much to do with the agency going from one of the nation’s worst at procuring donated organs for transplants to one of the world’s best.

“He knew what was needed to turn it around,” he said. “He has a tremendous business sense.”

“I just felt like the timing was right in the last year or so (to raise his transplant profile),” said Keith, whose personal story, Ham believes, has been extremely helpful in increasing donations and encouraging those with donated organs to live active lives.

What spurred Keith to willingly play a more public role in organ donation was the largely critical response to a talk he had been asked to give a couple of years ago when he sat on the donor network’s board. Survey forms handed out to the audience after his speech said he was too matter-of-fact about the transplant, that he didn’t show enough respect to his donor family.

“It turned out at that time that I agreed,” Keith said. “I was at a different time in my life.”

Not long after that 2011 speech, Keith made arrangements to meet the father of the 17-year-old English boy whose heart beats inside him. That young man, he found out, was playing soccer when he suffered a fatal brain aneurysm.

Keith, who was born in England, moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, when he was 2. When the wait for an organ seemed to be a point where death seemed a near certainty for their soccer star son, the Keith family decided to see if a transplant could be done 5,000 miles away in Great Britain. The search for an organ became well-publicized in British Columbia and people raised money to help the family with travel expenses.

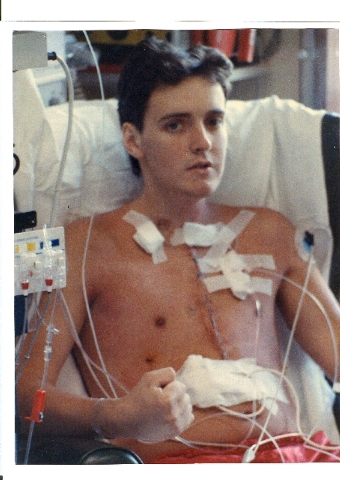

Seriously weakened by myocarditis, a deterioration of the heart muscle brought on by a virus, Keith barely made it through to the transplant. But once he did, it seemed as close to a perfect fit as possible.

“I didn’t have bad rejection issues,” Keith said.

The body’s immune system, the same one that protects us from infection and disease, tries to destroy a donor organ because it doesn’t match the recipient’s tissue exactly. Anti-rejection medicines, or immunosuppressants, are needed to decrease the immune system’s response so the new organ stays healthy. Keith still takes seven immunosuppressants each day.

The meeting with the 71-year-old father of the boy who died 27 years ago was emotional for both Keith and the man who felt guilty about his son being born with an imperfection that led to his death. Keith said he isn’t sure he could have met the man earlier and thanked him and still accomplished what he has.

“Back then one of the reasons that the psychologist said the donor family and the recipient should probably not meet up was that the donor family would have to grieve a death all over again,” Keith said. “I thought about that a lot.”

With that in his mind as well as constantly hearing that he had a 50-50 chance of living seven years with his transplanted heart — organ transplants were then in their infancy and long lives with a new heart weren’t on anyone’s medical radar in the ’80s — Keith said he “put blinders on” to shut out the emotion and negativity that surrounded a transplant.

“I really believed that the best way to say ‘thank you’ for the transplant was to live as normal and full a life as possible, to go full speed ahead,” he said. “I’m still not sure how to say thank you to a family whose loved one has given you everything — a career, a family, literally everything.”

(The book Keith published last year, “Heart for the Game” (Nexus Publishing), has a detailed account of his meeting with the father of the donor.)

Escape to UNLV

When Keith returned to Canada after the transplant, he found it virtually impossible to escape media and public attention. So when his brother Adam, who was already playing soccer for UNLV, said there might be an opportunity for him to make the team, he jumped at the chance.

Then UNLV coach Barry Barto, who had played professional soccer, gave Simon a tryout and liked what he saw, even though the young Canadian was still working his way back into condition. Still, he was understandably apprehensive about the transplant.

Barto, now an associate athletic director for special projects at UNLV, said he shared his concerns with Keith, who confidently told him that he wasn’t going to die playing soccer. “But if that’s what happens, it happens,” Barto recalled Keith telling him.

The coach talked with Keith’s parents, and doctors and lawyers. With liability questions resolved, Barto offered Keith a scholarship. The player made it clear he wanted to be treated just like everyone else.

“I really loved that time,” Keith said. “I could just be one of the guys.”

Barto, keenly aware of how difficult it is to get in top playing shape, was amazed that Keith was able to ready himself to play just months after his operation.

Now that Keith has decided he wants to share his transplant story, Barto is sure his former player will improve organ donation .

“He has such energy,” he said. “Once he puts his mind to something, he’s amazing.”

Not long after he finished playing at UNLV, he met his future wife in Vancouver. A month after they had been dating, he told her he had a heart transplant. “I was shocked,” Kelly Keith said the other day as she sat in the kitchen of the home the Keiths own near Southpoint. “In those days, the success of transplants was very low. But he was so casual about it, acted like it wasn’t a big thing in his life ... I came to realize he’s a different personality, highly competitive, very driven. ... He didn’t want to be limited because he had a transplant.”

Discussions with doctors convinced Kelly there was no reason the couple couldn’t have healthy children and look to the future. Simon’s health was, and remains, excellent. They have two daughters, Sarah, 26, and Samantha, 20, and a son, Sean, a 17-year-old soccer-playing senior at Bishop Gorman High School.

The only serious health complication the 5-foot 8-inch Keith has had, his wife recalled, is a staph infection following implantation of a pacemaker that monitors the rhythm of his heart. “We got through that, but he acted like it was no big thing.”

She said her husband’s Las Vegas cardiologist, Dr. Jacques J. Lamothe, appreciates that Keith “probably knows his heart better than anybody. ... He listens to Simon and doesn’t try to limit what he can do.” Lamothe was unavailable for comment.

HElping others live full life

Now that her husband, who remains near his playing weight of 170 pounds, is publicly telling his story as he works to increase organ donation, Kelly Keith said she has “never seen my husband so fulfilled.”

“He’s so passionate about what he’s doing,” she said. “I’ve never seen him so proud. He’s found a way to make a difference and a way to bring attention and awareness to something so important. It’s brought him tremendous joy.”

One reason Keith left professional soccer after two years on the field was the constant fielding of questions about his heart transplant. He could score a winning goal and the questions from the media later were about his heart, not about his play.

“That gets old when you’re a competitor,” he said.

He came back to UNLV and finished his degree in physical education and got an immigration green card so he could work. Having made friends here and having been able to live a life where attention was on his skill rather than his heart, he and Kelly decided to make Las Vegas home.

During the next 15 years, he built and sold four businesses, starting out selling promotional items such as key chains and caps. There was an import business with Taiwan. Later, he would work with sports stadiums and their concession merchandising.

With his personal background in organ transplantation, he was asked to serve on the board of directors of the donor network. But it wasn’t until the critical reception to the speech he gave on transplants, where he was told that he didn’t show enough respect to the donor family, that he began to really study organ procurement.

His analysis would turn into a position as chief operating officer at the donor network.

He found out that the local donor network was procuring about 24 organ donors per million population — each donor donates more than three organs — while top world networks had about 50 organ donors per million people. It wasn’t long before suggestions he made, working in concert with new CEO Joseph Ferreira, helped bring the number up to 36, and then 54.

The contact that the donor network had with the region’s 40 hospitals became closer as network staff communicated more through the latest computer technology and in person with hospital staffers about patients nearing end of life. And more staff was hired and professionally trained to deal with families during such a difficult time to talk about passing on the gift of life.

“We have an amazing team,” Keith said. “And we are still refining the process. What we have to do at such a horrific time for a family is not easy. But passing on life is so important.”

Whenever he gets the chance now, Keith tells his story.

“If it will help others, I will,” he said.

A few months ago, he was in Canada telling his story. Elaine Yong, a Vancouver-based TV journalist whose daughter needed a heart transplant shortly after her birth, was inspired by his talk.

“It was great to hear that someone was living such a great life so long after his transplant,” said Yong, who remains in frequent contact with Keith. “I need to hear that for my daughter, that she can live a normal life. What he’s doing now is so important.

“He’s using what happened to him for the greater good. He’s learned to take what life has given you and run with it.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@review journal.com or 702-387-2908.

DONOR FACTS

To become a registered organ donor people can register:

■ In person at the DMV by completing a simple form or checking "Yes" to becoming a registered organ donor on their driver’s license application/renewal form.

■ Online at www.donatelifenevada.org.

Quick stats:

■ 18 people die every day waiting for a transplant.

■ 40 percent of Nevadans are registered donors.

■ More than 5,000 Nevadans are waiting for transplants.