Las Vegas students with ADHD struggle to maintain, concentrate

They are the kind of students 10th-grade English teacher Christine White admits to having a soft spot for, and every school year it doesn't take her long to find them.

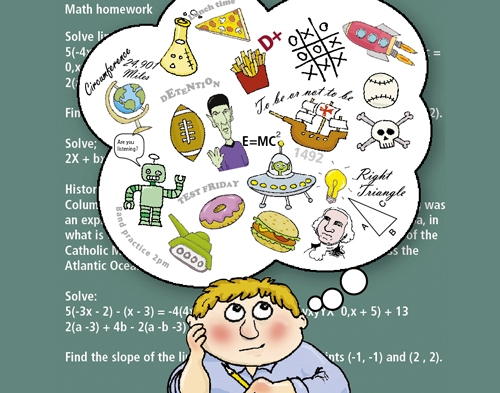

They're the ones who sit in the back of the classroom and always seem lost in their own thoughts, the ones who nearly always forget to bring in their homework or fidget in their seats as if they are an amalgamation of bones, muscle and rocket fuel.

She can't help her affinity. Often they are just like her 10-year-old son, bravely struggling with the symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, the neurobehavioral condition that has been in the news for years yet is still misunderstood unless, like White, you're caught in the middle of it.

One thing she knows for sure, the new school year can be a particularly rough time as students with ADHD plunge back into the routine of classes, homework and meeting the expectations of new teachers and peers.

If she could make one point perfectly clear, though, it would be that ADHD is not a choice and children with the disorder have the same desire to learn as anyone else.

"ADHD is virtually invisible. You have to be living in it. As a teacher I'm coming to learn that for the most part most kids are there to learn, they really want to, and if they're not, there's a reason - there's definitely a reason," White said.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is one of the most common childhood disorders, its symptoms often beginning to appear between the ages of 3 and 6, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Approximately 8.4 percent of U.S. children ages 3 to 17 have been diagnosed with ADHD, a total of about 5.2 million.

According to Ann Childress, a psychiatrist with the Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine in Las Vegas, having ADHD is like "trying to run the mile with weights on." The "weights" are ADHD symptoms such as being easily distracted, struggling with being organized, missing details, forgetfulness, becoming easily confused and not being able to sit still. The manifestations of the condition can vary, she added, with symptoms leaning predominantly toward hyperactivity, inattentiveness or a clear combination of the two.

While the symptoms can be addressed with treatments such as medication and behavior-modification therapy, there is no cure.

In the school environment - where children are expected to sit still for hours, remember instructions and not interrupt - having ADHD can be a significant challenge, to say the least. Trying to make others understand the intricacies of the disorder is a hurdle of its own.

One of the most important steps parents can take to help their child with ADHD succeed in school is to open the line of communication with teachers and administrative staff. In fact, there is such a significant disparity among educators in terms of what they know about ADHD that the role of parent-as-advocate is key, according to experts.

Robin Kincaid, training services director for Nevada PEP, which provides services and training to families who have children with disabilities, often suggests that parents write a one-page letter to teachers at the beginning of the school year explaining that their child has ADHD, how it affects them, their strengths and weaknesses, and what kinds of tactics have worked for them in the classroom in the past.

For example, if a child is easily distracted, a teacher could make sure the student's seat is away from an open doorway so they aren't bothered by people walking down the hallway, and seat them at the front of the room. The child also could be allowed to take tests in a quiet location away from other students.

Children with ADHD also can struggle with the repetition of homework, especially when they have already mastered a particular subject, Kincaid said. If they have finished those first 10 math problems successfully, for example, they may find the next 20 meaningless, so getting them to complete the homework can result in a drawn-out tug-of-war between parent and child.

"There should really be some set limits on how much time per subject that homework is part of a family's routine because sometimes kids (with ADHD) move so slowly, and so then that's when we look at: Should we reduce the homework? Do we do every other problem? Do we just demonstrate mastery?" she said.

Kincaid noted that a great way to communicate with busy teachers is to create a daily log that can go back and forth between school and home. The teacher can write down how the child did that day in the classroom, while parents can write information that might be helpful to the teacher.

"(The parent) may say the child had a bad night and didn't sleep well; this gives the teacher a heads up that this may not be his or her best day and so she might handle things differently," she said.

"I think you want to work on a real collaborative relationship. You want the teacher to know you're there, you're accessible, you want to work with them," she said.

Parents also can look into whether their child qualifies for an individualized education plan, or IEP, which would outline special education and other related services for the child, as well as specific goals for their education. There also is the 504 plan, which is geared toward making accommodations for a child in the regular classroom.

Nevada PEP has representatives who can help parents find the right contacts within the school district and navigate the paperwork, as well as accompany them to school conferences. In fact, they are often parents of ADHD children themselves, White noted.

"All you can hope for is a teacher that is at least open to the ideas that you have and wanting your child to succeed and everything," White added. "And even the ones that aren't receptive, I don't think that they don't want them to succeed, they just think they're doing better for them because they're showing them the hard-knock life. But it's a brain situation. The (ADHD child's) brain is different and they just don't get that."

Of course, what happens at home is crucial as well. The start of the school year means the beginning of a new, highly structured routine and that filters into the home. That's not always so bad for children with ADHD because often they do much better with the predictability of a structured day.

But sometimes the simplest routines are not so simple. A child with ADHD, for example, may wake up before anyone else in the house with lots of unbridled energy or struggle every morning to get out of bed.

"One of the biggest frustrations with this organization is getting them up and getting them out the door. You can get them up but they're supposed to get their clothes on, and then you find them in the living room and they're still in their pajamas and the cartoons are on," Childress said.

She stresses to parents how important it is for their children to get a good night's sleep and if mornings are a struggle, which they often are, the children can shower and set their clothes out for the next day the night before.

Often visual tools such as charts that list what needs to be done in the morning - making the bed, brushing teeth, eating breakfast, feeding the dog and catching the bus to school - can be used to help keep that focus as the tasks get checked off one by one, according to the experts. Timers are also a way to keep children on track so they know to spend only a certain amount of time on different tasks.

Many parents also use reward systems, Childress said, but that doesn't mean spending a lot of money. If a child likes to be read to, for example, it can mean 10 minutes of extra reading time with a parent. Since children with ADHD are into the "here and now," rewards should be given fairly promptly, she added.

White swears by the reward system and noted that it is usually much more successful than punishment.

"With ADHD, I tell you this, reward systems work better than anything else. You can do punitive until the cows come home and it almost never works, it won't last. And they get depressed and they get down on themselves. It almost always has to be reward where possible," she said.

When it comes to homework, it's a good idea for a child with ADHD not to put it off until late in the evening. According to Childress, the best time of day for children with ADHD in terms of behavior, concentration and attention is in the morning and "it kind of goes downhill from there." She also points out that medication is often wearing off by the end of a long day and can affect the ability to concentrate.

Homework also should be done in a place with as little distraction as possible so the child can stay focused, according to the experts, and preferably broken down into small steps. Long-term school projects should be worked on in steps as well, rather than pushed to the last minute, so the children don't get overwhelmed, they added.

Finally, parents of an ADHD child need to be on the same page as far as the strategies they use, they also need to help build the child's self-esteem by offering plenty of positive reinforcement and always point out to the child, even the rest of the world, what makes them extraordinary.

"You know what, the creativity that comes out of kids sometimes with attention issues is just unbelievable so we need to value all of their strengths and be focused on their strengths," Kincaid said.

Those interested in learning more or signing up for ADHD informational workshops can contact Nevada PEP at 388-8899, www.nvpep.org. There also is a local chapter of Children and Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, 533-2547; and the Nevada Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, 838-0742, is currently holding studies looking at the effects of certain medications on teenagers with ADHD.