Treatments for sleep apnea can help youths rest easily at last

Jared Rich tells people at parties, “I watch people sleep for a living.” He’s rarely believed.

But Rich, a sleep technologist, often does spend his nights hooking kids up with electrodes for the polysomnogram, a sleep study that can help physicians determine whether a child suffers from sleep apnea. That condition results when breathing pauses or is blocked during sleep.

At Children’s Lung Specialists in Las Vegas, activity picks up after 8 p.m. on a Sunday. The office resembles a dreamscape, encompassing everything from Bugs Bunny and Batman to princesses, nouveau art and Hawaiian vistas. Rich, who, himself, must sleep during the day, affixed wires to a little girl before she slept in a hotel room setup, complete with comfy queen-sized bed and television set. Her mother sat by the bed, chitchatting with Rich about catfighting “Housewives” on television.

“You’ve got 14 wires on your face and head,” Rich announced brightly. The little girl’s mother pulled out a camera.

“The queen is not queen-alicious,” pouted the girl, warding off the camera.

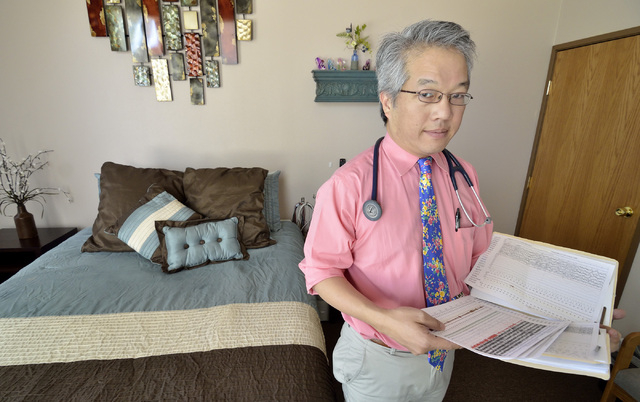

Her mother has physician Craig Nakamura on speed dial. Nakamura, director of Children’s Lung Specialists, is a board-certified pediatric pulmonologist. He’s gotten on the phone with her in the middle of the night, and stayed there as she rushed her daughter with debilitating asthma to the hospital. Nakamura ordered the evening’s sleep study, which should take only one night.

“He’s the kind of doctor you need,” the child’s mother said.

The jungle of sleep study paraphernalia ranges from electrocardiogram leads to a nasal cannula, belts across the chest and abdomen, and a movement sensor on the legs. It detects critical information, including seizure activity, heart rate, oxygen levels and leg twitching. After Rich spends about six hours monitoring the child’s sleep activity from another room, Nakamura interprets a vast collection of arcane lines. It’s all to help oxygen- and sleep-deprived kids and their families breathe a sigh of relief.

Otolaryngologist/ear, nose, and throat specialist Susan Schwartz treats local children for some of the most common ear, nose and throat disorders — including a few sleep apnea cases per month. Parents arrive scared, she said.

“They come in, saying ‘I’m watching my child not breathing at night. Doctor, watch this. I taped him. Why is my child gasping for air?’ ” she said. “That’s when you educate the mom and say, ‘That’s sleep apnea.’ ”

Nakamura said the two types of sleep apnea are obstructive, in which a blockage prevents proper breathing, and central, in which the brain pauses and forgets to reboot. Sleep apnea is most common in children ages 2 to 6, he said. Children’s tonsils and adenoids reputedly undergo the greatest growth in that age range, sometimes blocking the breath.

And, he added, about 1 percent to 2 percent of all children may have obstructive sleep apnea — or, 5 percent of children who snore.

“If you take the whole Clark County School District, there’s a lot of kids who may have sleep apnea,” he said.

Sleep studies at his office started more than two months ago, with a steady stream of about four patients per week, although, he estimated, “We could easily do every night a week.”

Some young patients at the office have narcolepsy and night terrors. Others are sleepwalkers, restless-leg syndrome sufferers, and kids with disrupted sleep cycles resembling the shift disorder experienced by adults who work nights or irregular shifts.

For children, sleep apnea can translate into less-restful sleep, and therefore, constant exhaustion, headaches and bedwetting. It can affect behavior, school performance and future studies as well.

“If you don’t do well in the low level math, you’re probably not going to do as well in the higher level math, because you need to grasp those fundamentals to progress,” Nakamura said.

More dangerously, teenagers can fall asleep at the wheel. And, severe sleep apnea can lead to reduced oxygen levels. That, in turn, can lead to pulmonary hypertension, causing the right side of the heart to grow larger and work inordinately harder.

Asthma and obstructive sleep apnea can also interplay, said physician Julie Baughn, a sleep and pulmonary specialist at Mayo Clinic Children’s Center.

“Asthma is an inflammatory condition, and obstructive sleep apnea has also been shown to be an inflammatory condition,” she said. “Inflammation of the upper airway causes sleep apnea. Inflammation of the lower airway causes asthma. Obstructive sleep apnea can have an impact on asthma, and vice versa.”

Schwartz said the American Academy of Pediatrics identifies obstructive sleep apnea as a common condition in childhood that results in severe complications without treatment, including cardiovascular problems.

“Pediatricians now are recommending that children regularly get screened for snoring to make sure they don’t have sleep apnea,” she said.

Most children who have obstructive sleep apnea are cured by having their tonsils and adenoids out, Baughn said. But Schwartz said when surgery isn’t an option or it doesn’t work, a CPAP mask worn over the nose, or the nose and mouth, during sleep can provide continuous positive airway pressure. Gentle air pressure from a machine keeps airways open. There’s also a special dental appliance for mild apnea. In severe cases, a tracheostomy, involving a tube in the neck, may be an option, Nakamura said.

With childhood obesity increasing, excess girth can also interfere with breathing. In those cases, Schwartz recommends weight loss. She also orders a retest after weight loss and the surgery she performs. In some cases, she said, kids grow out of the apnea.

Although no breakthroughs in treatment are on the horizon, Baughn said awareness is growing.

“The main thing is that we’re getting more increased recognition for this problem,” Baughn said. “Parents and primary care providers are recognizing the importance of sleep in children’s development.”