Self-publishing stirs debate in book world

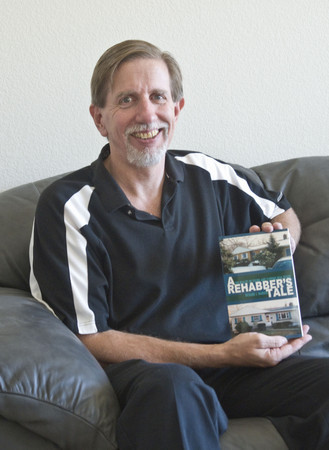

When Richard Warren would give presentations about buying, rehabbing and then reselling homes, audience members often would ask him if he had a book they could buy.

Until recently, the answer was no. But the repeated requests got Warren thinking. And, now, interested audience members can take home copies of "A Rehabber's Tale: The Reality of Fixing and Flipping Real Estate," the guide Warren published at a cost of just under $1,000.

Michael Philip Pernatozzi also took a self-publishing tack for his Las Vegas-based crime fiction thriller, "Collusion on the Felt." Pernatozzi figures that, so far, he has invested between $5,000 and $6,000 in his book.

For Warren, paying to publish was a worthwhile way to speak to a narrowly defined target audience. In contrast, Pernatozzi has struggled to get his self-published novel into readers' hands.

Such are the ways of self-publishing, which turns the traditional book publishing model on its ear by asking authors to pay the costs of getting their books into print.

Las Vegas-based author Jay MacLarty, who has published four political thrillers with Simon & Schuster, is a leader of the Las Vegas Writers Group where, he says, self-publishing is a much discussed, and often little understood, issue.

MacLarty recalls one session at which a woman in the audience asked a Las Vegas author -- a best-selling author who has a multibook deal with a traditional publisher -- how much she paid to have her books published.

"It's like (self-publishing) is all these people are hearing," MacLarty says.

By the way, the answer is: nothing at all. Neither MacLarty nor his fellow established author pay a penny to have their books published. Further, when publishers buy their manuscripts, the authors receive advances, and then royalties after the books are published, and they pay none of the costs associated with printing, editing, marketing or distributing their books.

In contrast, self-published authors pay a fee to a publisher to have their manuscripts published, and they also may pay additional fees for such things as editing, cover designs and press releases to reviewers and media outlets. And, while the published books will be listed for sale on Amazon.com, BarnesandNoble.com and other online retailers, distribution or marketing beyond that typically is left pretty much to the author.

But, regardless of the business model or the self-publishing agreement signed, that remains the litmus test of a self-published book: The author has paid to get it into print.

There's nothing wrong with that, necessarily. But, MacLarty says, that's only as long as the author understands that self-published books present challenges traditionally published books don't.

First, MacLarty says, "you don't get reviewed when you self-publish. None of the traditional, legitimate newspapers or media will review a self-published book, and (authors are) never told that when they go to these vanity press things. They may be able to go down and talk to somebody in their local area to cover their book, but no one else will."

Kevin A. Gray, public relations manger for Author Solutions, parent company of popular self-publishing brands AuthorHouse, iUniverse, and Xlibris, says that's not unique to self-published books.

"I get dozens of alerts every week of our books being reviewed in newspapers across the country," he says, from local publications to USA Today to -- for the handful of self-published authors whose books are later picked up by traditional publishers -- talk shows.

Gray advises self-published authors to "start local and work their way up." Recently, according to Gray, one self-published author landed on the "Today" show after a producer saw a local newspaper story about her book.

Distribution is another challenge for self-published authors, according to MacLarty. For example, while a self-published author will see his or her book listed on Amazon.com, "people don't realize Amazon has 6 million pages," he says. "What are the chances of someone finding your book out of 6 million pages?"

Meanwhile, MacLarty continues, "you can't get into Barnes & Noble and Borders (stores), which are pretty much the only bookstores left. It's got to go through (corporate headquarters in) New York, and they don't even look at self-published (books)."

So, MacLarty says, "there's no reviews and no distribution. And the name of the game in selling books is review and distribution."

For fiction in particular, self-publishing is "a terrible option," MacLarty adds, although, for authors who intend to serve a narrowly defined target audience, it can be at least one option to consider.

Take Warren's rehabbing guide. "For me, self-publishing was absolutely the way to go, simply because I had a particular audience that was basically a niche market," Warren says. "It was not a mainstream type of book."

And, while he hadn't envisioned making money on it, Warren says he has now "covered my costs and then some."

Pernatozzi initially tried the traditional publishing route with his Las Vegas-based crime fiction novel, and even had an agent back East who, he says, "had it for four or five years but never did anything with it."

Then, about a year ago, Pernatozzi published the book through iUniverse. He estimates he so far has invested between $5,000 and $6,000 on "Collusion on the Felt."

The book is available on Amazon.com and BarnesandNoble.com, and Pernatozzi has sold some books at signings. But, he says, "when I approach people like bookstores and Costco, they would look at you like you're nuts. So you are an unknown out there."

So it has been an uphill battle? He laughs. "I'd probably say it's more like vertical."

Pernatozzi estimates he has sold "probably under 50" books so far, and says he knew he "wasn't going to get rich, but I wanted to get published."

Also, Pernatozzi says, "one thing I don't like about iUniverse is they keep coming back afterward, offering you opportunities to have your book in front of librarians or a mass mailing. So it's a lot of money, and you pay for it. It never gets any response. Nothing ever happens."

Gray says Author Solutions' imprints do "offer marketing opportunities. Obviously, they're optional."

But, he adds, "we encourage our authors, beyond that, to be very, very active in promoting (their) books.

"I've read some very good books that may not have sold a lot just because they have not been promoted by the author very well, and I've seen authors of pretty good books promote like crazy that have sold a lot of copies."

Las Vegas attorney Charles Titus found self-publishing with iUniverse a good way to give his crime thriller, "Vegas Diary: A Dish Served Cold," a test run in the literary marketplace.

"It's my first novel. That's why I chose self-publishing," he explains. "I wanted to see if it is going to be something I could do that will actually be accepted by the public."

Titus estimates he has invested about $1,100 in the effort, which included an editorial evaluation and, he says, "a great job with the artwork."

Titus says his research revealed that the average self-published book sells about 70 copies. After eight months, his novel has sold about 600 copies. Still, he says, "you're not going to get rich off of that."

The only real negative, Titus adds, "would be that you have to self-promote, and you have to kind of sell, and I'm still fairly busy practicing law, so I don't have a lot of time to do that."

Brian Rouff, on the other hand, is managing partner of Imagine Marketing, a Henderson marketing and public relations firm. That may help to explain why his self-published novels, "Dice Angel" (2002) and "Money Shot" (2004) so far have sold, he estimates, a combined 35,000 copies.

"That's not really typical, but I'm a marketing guy," Rouff says. "I don't recommend it to people who think it's going to be easy. It's actually the toughest thing I've ever done."

Before deciding to self-publish, Rouff spent about 18 months pursuing the traditional publishing route. "I had a couple of different agents," he says. "I came real close to a couple of deals with, not a huge publisher, but legitimate midsized publishers. But at the end of 18 months I didn't have anything to show for it, nothing other than experience. I learned what not to do."

So, he embarked on a very literal definition of self-publishing: He founded his own publishing company, Hardway Press -- "Because I was doing it the hard way" -- hired an editor to work on his manuscript, hired an artist to design a cover and hired a small-run book printer in the Midwest to print books for him.

Rouff said he had checked out self-publishing companies, but felt that, back then at least, "the quality of the product that came out of the iUniverse model, print on demand or whatever, was not up to what I was looking for."

"In order to make any kind of impact on the market, your book has to be as good as or better than anything coming out of the big publishing houses," he explains.

Rouff says he still hasn't made money off of his books, mostly because "I kept plowing it back into printing more books and book promotion."

It is, he adds, "literally a labor of love."

MacLarty says aspiring authors who are considering self-publishing should educate themselves and, then, have reasonable expectations about what it offers.

"If somebody wants to self publish, we're not going to say, 'We don't support you' '' he says. "But we want them to know what they're getting into."

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.