Writer brings characters to life in comics, novels

Women, as a gender, don’t always fare particularly well in comics.

There are women comics characters who exist only as helpless females, and women comics characters who exist only as clumsy cardboard figures, and women comics characters who exist merely as cheesecake.

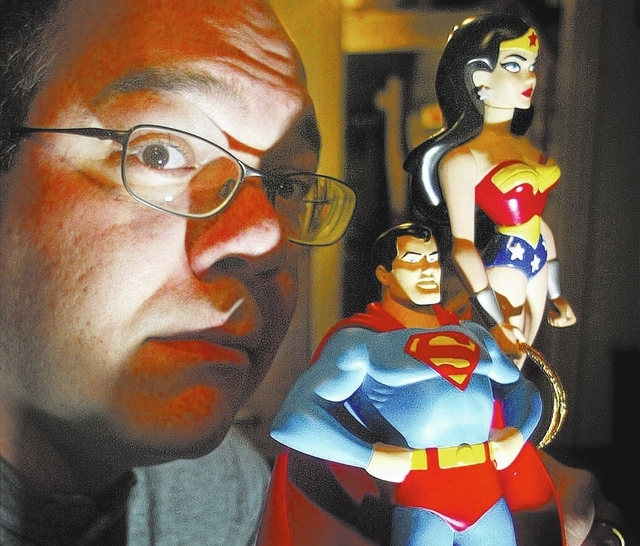

And then there are Greg Rucka’s women comics characters. In his comic books and novels, women characters invariably come with fully formed, complex personalities and rich back stories, be they British spies (Tara Chace from Rucka’s “Queen &Country” comic/novel series), deputy U.S. marshals investigating murder in Antarctica (Carrie Stetko in Rucka’s graphic novel “Whiteout) or even a certain iconic Amazon (Rucka’s acclaimed run writing “Wonder Woman”).

Rucka will be in Las Vegas Saturday to participate in “The Enemy of Inertia: Spotlight on Greg Rucka,” a program that is part of the Vegas Valley Book Festival and Vegas Valley Comic Book Festival.

The session, moderated by journalist F. Andrew Taylor, begins at 1 p.m. in the main hall of the Clark County Library, 1401 E. Flamingo Road.

During a recent phone interview, Rucka, the recipient of several Eisner awards — the comic world’s Oscar/Emmy/Grammy/Tony — recalls that he discovered comic books “the way most kids do.”

“I was very small and I remember bugging my mom for a black-and-white reprinted, digest-sized collection of (Jack) Kirby and (Stan) Lee Incredible Hulk stories in the supermarket,” he says.

But, Rucka continues, “in all honesty, I really didn’t get into comics until high school when I fell in with a group of friends who were devoted Marvel zombies. That became sort of a shared experience, a shared interaction.”

Rucka is unusual in that he works in both comic and prose literary forms, even within the same series. For example, his “Queen &Country” series began as a series of comics, then continued in paperback novels.

“One of the nice things about being able to at least feel that I could competently write a novel — as I feel that I can competently write a comic — is that it does offer the luxury of which medium best suits the story,” Rucka says.

“ ‘Whiteout,’ I’m not sure I could have written that as a novel. It’s much better as a comic. ‘Queen &Country’ works very well for both, I think.”

Rucka says working in both forms also allows him to flesh out scenes, character bios and bits of back story that would be lost in a comic.

“The nice thing about Queen &Country is that, for lack of a better phrase, my oversight is absolute, so there were elements I had always known about when I wrote the comics that were just never going to be visible in the comics,” he says. “So I had always known that once the opportunity for prose arose, I was going to be able to share those.”

Writing prose is “a very different type of writing for me,” adds Rucka (who also has written a popular series of novels featuring a bodyguard named Atticus Kodiak).

In a novel, the prose is “meant to be ingested directly by the reader,” Rucka explains, while the words used in writing a comic also are written for an artist and others — letterers and colorists, for instance — who collaborate to make the writer’s vision realized.

“I tend to view comic writing more as an epistolary form, frankly,” Rucka says, and collaboration is “the beauty of comics, in a way.”

Yet, comics remains a storytelling form that many avid readers still eschew. Is acceptance of comics and graphic novels as a valid literary form any more widespread today than it once was?

“It’s a little better,” Rucka answers. “It’s not substantially better.”

There are excellent stories being told in comics today, he says, but comics also suffer from “a legacy of 80 years of incredibly bad stories.”

Also, Rucka says, the language of comics “is quite literally a visual language, and many people actually were never taught to read it. So they don’t know how to read a comic, but they can see the imagery, and the imagery itself in many cases is rightly pretty offensive.”

Many mainstream comics “are sexist (and) they are over-the-top with their violence,” Rucka says, “and they’re not getting better at that.”

The sexism that does exist in many comics probably helps to explain why Rucka’s more fully realized female characters are considered by so many readers to be so noteworthy. Rucka says depicting female characters in a more real, more complex way stems from his enjoyment of research and his belief that good writing requires “servicing details.”

“I like women. That’s what it comes down to,” he says. “First and foremost, I like women. I enjoy their company. I’ve never been afraid of them. This is how I was raised.

“I was raised in a house where ‘feminism’ was not a dirty word. It was considered as fundamentally patriotic a concept as anything you could throw allegiance to. The idea that there would be gender equality that would be justified was something that would never hold.”

But, Rucka says, “it is fiction and, at the end of the day, all fiction is picking the right detail. A character’s gender is a detail of the character, but not the only detail of the character, and being able to work with that and understand that and understand its limits I think helps.”

There are comics in which “there is in no way an acknowledgement of gender, and that’s not truthful writing,” he says. “Good writing, whether it’s sci-fi, fantasy or what-not, the writing, if it is going to be good, has got to have truth to it.”

Rucka’s resume includes writing for both Marvel and DC for a cast of characters that includes Batman and Superman. For several years, he also wrote a highly regarded run of Wonder Woman before DC let him go.

“One of my biggest regrets in my comic career was losing that job,” Rucka says.

He laughs. “It’s been 10 years, so I really have to get over it. But to this day it bugs me. I feel like when you get a character like that, like Wonder Woman, it’s a privilege. For all of the silliness — and there’s a lot of silly stuff — it’s a privilege to be able to write for an icon of that scope and power, and you want to honor that.”

How does a writer approach a character — a Wonder Woman, a Batman, a Superman — that has achieved iconic status? First, says Rucka, “I tend to focus very strongly on character. I’ve always considered myself a character writer.”

Then: Honor the character, but don’t be intimidated by whatever it is an audience may expect.

Rucka has found that “you cannot focus so much on the audience, because if you stop and think, ‘Wow, this character has a 75-year-old history and a lot of people are very invested in it,’ there’s a good chance you’re never going to do anything.

“I try to approach it with the clear understanding, at least from my part, that what I’m being offered is an opportunity to work on something much bigger than myself, and try to serve that character the best I can in the time you’ve been allotted.”

Rucka’s current projects include a steampunk-themed webcomic, “Lady Sabre &the Pirates of the Ineffable Aether” (www.ineffableaether.com). His “Queen &Country” spy series reportedly is heading for the big screen (Ellen Page reportedly is interested in starring). And Rucka says a new comic series, “Lazarus,” is “a science fiction kind of thing” that “we’ve had lovely response to.”

Rucka also is expanding his own literary repertoire via a horror series for Dark Horse Comics.

Actually, he says, “it’s being billed as horror, and I’ve never even considered writing horror in my life. That whole genre is one where you can end up deep in the weeds.”

But, Rucka says, “it really is: What is the story? Genre labels are always dicey.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.