Law enforcement culture, training calls for coming on strong to end situations

In 2002, former Las Vegas police homicide Detective Dave Hatch published his first book, a how-to guide for investigating officer-involved shootings.

Hatch was uniquely qualified, having spent more than a decade investigating police shootings and teaching his methods to police nationwide.

Clark County Sheriff Jerry Keller, his former boss, gave it a ringing endorsement: "I can think of no one better qualified to write on the issue and their experiences with OIS/police-related deaths and the investigation of same."

In the book, Hatch warned against letting narcotics detectives serve forced-entry warrants in raids on the homes of drug dealers.

"Having narcotics officers make entry is at best a questionable practice," he wrote in recommending that raids be done only by specially trained officers.

His own department failed to take his advice, and it cost Trevon Cole his life.

In June 2010, Cole, a 21-year-old small-time marijuana dealer, was killed in a botched raid on his East Bonanza Road apartment by a narcotics detective, Bryan Yant.

Only after the shooting was ruled justified by a coroner's inquest — eight years after publication of Hatch's book — did Sheriff Doug Gillespie order that only SWAT officers could serve forced-entry warrants.

In a yearlong investigation, the Review-Journal analyzed Las Vegas police's 310 officer-involved shootings, which include 115 fatal incidents, since 1990. That analysis shows a department that does little to hold cops accountable for mistakes and often fails to correct deficiencies in training and procedure. With little pressure to change from an apathetic community, the Metropolitan Police Department remains insular and slow to weed out problem cops or adopt better ways.

AVOIDABLE SHOOTINGS

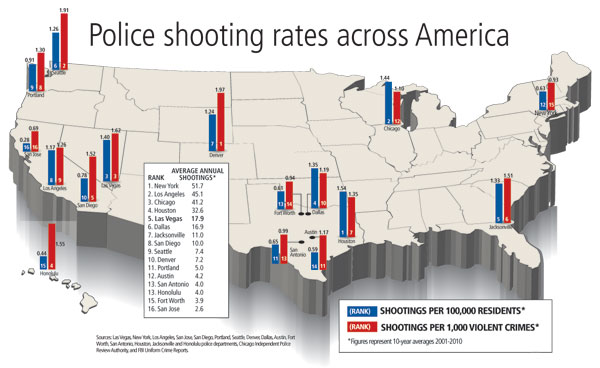

In a Review-Journal survey of 16 police departments, Las Vegas police rank high in two key measures: third in both the rate of shootings per capita and in shootings per reported violent crime. Last year the department had 25 shootings. For the first 11 months of 2011 it's had 16, though it has set a new record with 11 deaths.

The department's propensity to shoot hasn't gone unnoticed, and even law enforcement insiders express concern.

"I always thought there were too many shootings," said Bill Keeton, who investigated them as a Las Vegas homicide sergeant before he retired.

Asked whether he thought the Las Vegas Valley had too many shootings, former Sheriff Bill Young, now head of security for Station Casinos, said, "More than what I'd like, and more than almost all our citizens and more than most police officers obviously like."

So why do they happen?

Many are a necessary part of law enforcement.

But the history of the Las Vegas police is replete with examples of reckless behavior by officers leading to shootings that were legally justified yet entirely avoidable.

Take incidents where officers shoot a driver to avoid being injured or killed by a moving vehicle. Many police agencies have strict rules on how officers should act when on foot around cars. The Police Executive Research Forum, based in Washington, D.C., says it's best to prohibit officers from reaching into a vehicle to wrestle with a driver or passenger. Better to let them go and call in backup to stop them down the road.

Those policies help prevent the kind of incident that ended with the death of Douglas Oswalt.

In May 1999, officer Gregory Ziel and his partner tried to arrest a man suspected of selling stolen tools in the parking lot of the Palms Business Center on Industrial Road. The man ran from them, jumped into Oswalt's pickup and told him to drive. As Ziel wrestled with the theft suspect the truck took off, and Ziel clung to the passenger to avoid being dragged and possibly killed. Both cops shot at Oswalt. Ziel's bullet killed the 32-year-old, who paid the ultimate price for involvement in a minor crime.

That death was ruled justified by a coroner's inquest jury. A year later, following two nonfatal shootings under similar circumstances, the department warned officers to be more careful, but didn't tell them not to reach into cars.

Seven years later, Las Vegas bicycle officer Noel Lefebvre during a routine traffic stop on the Strip reached and fell into a car as it was pulling away. His partner, officer Ryan McBride, then shot and killed the driver, Tarance Deshon Hall, 31. The crime that set off the deadly events? Hall's stereo was too loud.

Las Vegas still has no policy on reaching into cars.

A similar failure to adopt modern tactics for dealing with suspects who are armed with knives or other "edged weapons" has contributed to several shootings.

The Police Assessment Resource Center, a Los Angeles-based think tank, recommends letting officers back away from suspects who aren't an immediate threat, giving themselves plenty of space and time to de-escalate the situation. Las Vegas' culture and training calls for the opposite: Control and contain the situation, come on strong and end it.

In 2004, for example, officers dealing with a suicidal woman armed with a knife first tried it the PARC way. They offered to trade a beer for her kitchen knife, and she agreed.

But the offer wasn't genuine. As the woman reached for the beer can, she was shot with a less-lethal beanbag shotgun round and a Taser. Far from incapacitated and still holding the knife, she ran toward her apartment, directly at Sgt. Kathy Kosmides, who was blocking her way. The sergeant, feeling boxed in, shot her in the leg.

HALF MEASURES

Even when the department does address problems, it often stops short of fixing them.

The Review-Journal found that nearly 25 percent of Las Vegas police shootings come after a foot chase.

The International Association of Chiefs of Police calls foot chases "inherently dangerous police actions" because suspects can turn and ambush a lone cop in pursuit. When that happens, either the cop or the runner can be hurt or killed. A Las Vegas police officer was shot and nearly killed last year in just that situation.

In 2003, the organization recommended that departments adopt policies that officers avoid or end a chase when they are alone, lost, lose contact with other officers, or if the suspect runs into a building unless there was an immediate threat.

Last year Las Vegas adopted that policy almost word for word, but with an important difference: Here it's just good advice, not mandatory.

Slowness to evolve isn't limited to shootings. In 1992, officer Donald Weese was killed in a crash while speeding to a call. Four civilians subsequently died in crashes attributed to reckless driving by officers, the most recent in 2007.

Yet the department waited until 2009 to address the problem — after officers James Manor and Milburn "Millie" Beitel died in separate crashes that year. Officers are now restricted to driving no more than 20 mph over the speed limit unless they're chasing someone.

Former Undersheriff Rod Jett, the department's second-in-command when he retired last December, agreed that Las Vegas police are slow to react to problems.

"From my perspective, too many events were allowed to occur prior to change being implemented," Jett said recently. "I thought the organization was too slow to implement change ... that really changed the behavior of the organization."

Gillespie argues that his department is adaptable and has worked to reduce shootings. He cited the department's adoption of Tasers, recent changes to training for shooting at vehicles and the relatively new driving policies as changes that have had an impact. He said the new foot pursuit policy, while not mandatory, has reduced the number of shootings during foot pursuits. Last year Las Vegas had seven. This year, two, including a fatality this month.

"I think when you take a look at a number of things that we've done over the years, not only have we reacted to situations that have occurred, we've been proactive in our response to it," he said.

LAX ENFORCEMENT

Setting policy is important, but so is enforcing it. Here, too, Las Vegas falls short.

The department has a Use of Force Review Board that is supposed to cast a critical eye on serious incidents and recommend corrective measures, including discipline or changes in training, policy or tactics.

Trouble is, the board seldom sees anything amiss: It has ruled in the officer's favor more than 97 percent of the time since 1991. Even longtime members call it ineffective, or worse.

But the board is often limited in what it can do. When policies are only advisory, as is the case for foot chases, Las Vegas police can't discipline officers for failing to take good advice.

Not that the board worries much about rules. Las Vegas police have had a strict policy against shooting at cars for at least 10 years, but the board routinely declares deviations from that rule to be justified. Officers have an out: if their life is in danger, they can break rules. Jett said that sensible exception is liberally applied.

"Once violations occurred where people clearly could not articulate a deadly force threat, they were allowed to provide excuses and they weren't held accountable," he said.

On the rare occasion the board finds poor judgment or violation of regulations, the offending cop has little to fear. After taking office in 2007, Gillespie dramatically reduced penalties short of dismissal to a maximum of 40 hours unpaid suspension. Officers can opt to forfeit a week's vacation, instead.

Last year's death of Trevon Cole, while ruled justified by both a coroner's inquest jury and by the Review Board, revealed Yant's sloppy police work, major errors in search warrant affidavits and other problems before and during the fatal raid. Yant's punishment: A 40-hour suspension — exactly the same as two Las Vegas officers who blew off work in January and drove their cruiser to Arizona on a lark.

Gillespie in an interview defended the reduction, saying it's important to get the officers back to work. Still, he said he is reviewing the policy to see if it's effective.

More than anything, Gillespie said, citizens hold their fate in their own hands.

"I think it could have been prevented if Trevon Cole would have done what was asked of him, No. 1," he said. "We can speculate all day long, what would happen if we didn't serve the warrant. The reality is, we did serve the warrant. And then, based on that search warrant service, we've modified some of our department policies. Would that have prevented it? That would be speculation on my part."

Gillespie said much the same thing about 2010's other highly controversial killing, that of medical device salesman Erik Scott, 38, at a Summerlin Costco store.

The department performed a tactical review of the Scott shooting that included an officer's decision to tell the Costco manager to evacuate the crowded store, causing hundreds of people to funnel out one exit. As Scott and his girlfriend went out the door, three other officers pointed their guns at him, ordered him to the ground and then shot him when he pulled out a holstered handgun he legally carried. All seven shots hit Scott and no one else was injured, but critics questioned whether the evacuation order and shooting in a crowded area endangered the public more than Scott's prescription drug-induced odd behavior, which had unnerved a store employee.

"That's one of those conclusions where there's not necessarily a right or a wrong," Gillespie said of the decision to evacuate the store. "(If) Erik Scott would have listened to what the officers said, it would have ended considerably different than it did, but he chose not to."

Last year Gillespie created two new teams to handle police shootings, a departure from the department's longtime practice of having only homicide detectives investigate. The Force Investigation Team, a group of homicide detectives, will continue to probe the facts of the case while a Critical Incident Review Team examines tactical decisions of the officers, whether policy was violated and whether any policy or training should be changed. Typically, FIT investigates before CIRT steps in.

The sheriff calls the teams the foundation of efforts to reduce officer-involved shootings, developed after months of study.

But there are doubts about the effectiveness of the two groups. Other departments also have two review teams, but they're usually more integrated, with members of both participating equally in interviews and doing parallel investigations. Most law enforcement experts say this approach strengthens both.

"I'm surprised they don't do that," said Geoff Alpert, a University of South Carolina professor who studies police use of force. "I don't understand how they can not have that approach."

Larry Hanna retired this year after eight years as a Las Vegas homicide detective. For the last eight months of his career he was assigned to FIT. The team was supposed to get special training to do better investigations and produce more consistent reports, he said.

Hanna saw none of that.

"There was no additional training. I didn't receive any," Hanna said. "There was nothing that made the reports consistent. And for all I can see at that point was a political move. Gillespie can say, 'Here's what I'm doing. I made a special group that will only do these (police shootings). They're special.'"

Jett said he had doubts about FIT from the start because the team lacks independent oversight. He said Gillespie was initially receptive to adding a deputy district attorney to the team for outside oversight, but decided against it until he could find money to fund the position.

"Right then I knew that that was a mistake," Jett said. "It's too easy to say, 'We don't have the resources, the DA didn't have the budget,' and once the controversial issue has gone away, status quo is in place and there's no real motivation to bring on the second component that really makes the team viable and effective."

Gillespie said both groups are still a work in progress, and that he is not yet sold on the idea of involving prosecutors.

NO PUSH TO CHANGE

Formed in 1973 by merging the Clark County Sheriff's Office and the Las Vegas Police Department, the Metropolitan Police Department is a relatively young agency that grew rapidly as Las Vegas boomed. From about 1,000 officers at its start, it now has more than 2,600, plus 1,300 civilian workers.

The department is unusual among American urban police agencies in that it operates largely on its own. A joint city-county committee sets the budget, and a Citizen Review Board with little authority reviews some citizen complaints, but no outside entity monitors policy or day-to-day management by the elected sheriff. That's especially true for hot-button issues such as use of deadly force.

"It's the million-ton gorilla in the room, and nobody wants to talk about it," said University of Nevada, Las Vegas political science professor David Damore, who called it a "no-win" for politicians.

Clark County commissioners come closest to the no-win zone because coroner's inquests are governed by county ordinance, but commissioners are limited in what they can do.

While the sheriff faces voters every four years, those elections seldom get much attention in a city where few residents have deep roots. Always landslides for a well-established candidate, the elections don't bring in fresh blood and new ideas. All six sheriffs since the merger graduated to the top job after long careers in the department.

The department in recent years has also been remarkably insulated from outside political pressure. Twenty years ago it instituted some reforms in response to rare protests and demands for more transparency and oversight from organizations, churches and elected officials with roots in predominantly black West Las Vegas. The cause at hand was the death of Charles Bush, a black man who was choked to death in his home by three white officers.

Those people and institutions have dissipated with the city's expansion and lowering of racial barriers. The fact that blacks make up less than 10 percent of the Clark County population but account for 32 percent of Las Vegas police shooting subjects — including Trevon Cole — hasn't spurred community outrage.

"Las Vegas has long suffered from a lack of introspection," local historian and College of Southern Nevada professor Michael Green said. "We don't think enough about what we're doing now and what we intend to do later."

INTERNAL INERTIA

Jett, the former undersheriff, said administrators are reluctant to push for strong policies because they fear exposure of problems that could be used against the department in lawsuits. That caution is misplaced, he said, "because we're already paying. ... We're losing taxpayer dollars, and at the same time we're eroding the public's confidence in the organization."

Resistance from police unions, and fear of taking on that politically powerful force in pro-labor Las Vegas, also factors into a departmental culture that favors the status quo.

Shortly after he took office, for example, Gillespie wanted to require all officers to wear body armor — a common rule elsewhere. But the union resisted, saying protective vests are a condition of employment subject to contract talks, not something the sheriff could mandate.

Gillespie had to compromise: Only officers hired after 2008 must wear vests.

The sheriff ran into the same resistance last year when he backed changes aimed at making the coroner's inquest less favorable to officers. The Police Protective Association told members to stop testifying at inquests, then backed cops who filed a lawsuit that shelved the entire process.

"The police union has fought any effort to change anything. ... I don't think they're serving the public well," said former Clark County Commissioner Rory Reid, who left office in January.

Leaders can limit deadly force

In 2002, the U.S. Department of Justice identified the attitude of a department's leader as a "key factor" in limiting use of deadly force and in maintaining public confidence when it is used.

"If the chief stresses conduct that respects the sanctity of human life, and follows up through close administrative review, line officers will respond accordingly," the agency said in a report.

After police in Portland, Ore., had their fifth shooting in 40 days earlier this year, Chief Mike Reese called in outside experts for a policy review. After a similar review in 2003, Portland saw a 50 percent reduction in police shootings.

"We're going to do everything we can to prevent officers from having to use their firearms," he told the city's newspaper, The Oregonian.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca in 2001 called for and helped create an independent agency to monitor his department's internal investigations, including police shootings. When reports of abuses at the county jails emerged this year, that office issued a scathing report uncovering serious problems.

Gillespie hasn't been as proactive in public, but he has hired a group led by a University of California, Los Angeles professor for a long-term study of training and racial sensitivity. He also said he has sought advice from community leaders about ways to make the Use of Force Review Board more effective and ideas for better reporting on nonfatal shootings, which often are made public only through terse news releases. No plan has been formulated, however.

He also said he would consider allowing civilians to observe shooting investigations but would oppose creating a formal independent monitor or auditor with authority to look at policies and procedures.

Review-Journal reporter Brian Haynes contributed to this report.