Another million neighbors?

Clogged highways. Crowded schools. Long lines everywhere, from the DMV to the emergency room.

Welcome to life alongside 2 million people. Or, as future Clark County residents might call it, small town living.

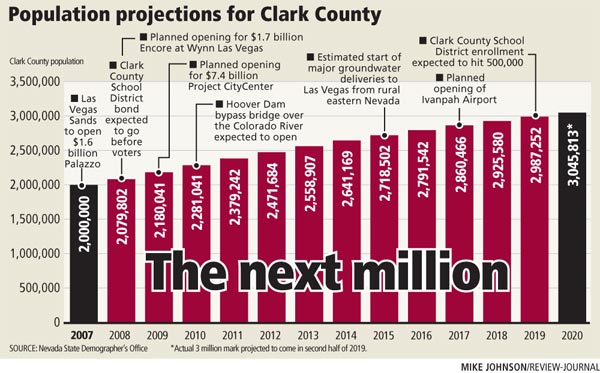

According to the latest projections from local demographers, the county is on pace to add about 85,000 people a year through 2019. That's when the population is expected to surge past 3 million, 12 short years after pushing past the 2 million mark.

So what will life be like in Clark County as the next million arrives?

By then, the county should have a new regional airport near Primm to take the strain off McCarran International Airport, and widened stretches of Interstate 15 and U.S. Highway 95 to carry a growing armada of commuters.

New pipelines will reach into Lake Mead and to groundwater basins across eastern Nevada in search of water for all those newcomers.

Visitors to the Strip will flock to several glittering new megaresorts, which will be the largest monuments to prosperity and pricey club drinks ever built here, at least until the next ones are built.

What will any of this mean for Clark County residents new and old?

Can the quality of life here survive the crush of a million more souls?

Urban planner and commentator Robert Fielden worries about that.

Fielden is an advocate for mass transit and an enemy of sprawl who regularly speaks his mind on local public radio station KNPR.

Already, he sees signs of trouble ahead, as the county's surging economy threatens to overwhelm public services, infrastructure and the desert itself.

"It's not sustainable. That's the crux of the problem," he said.

Fielden also thinks most growth projections are low.

He said the 2 millionth resident probably got here four or five months ago, and the 3 millionth resident will undoubtedly arrive well before 2019.

At that pace, Clark County's population could top 4 million as early as 2025, "if the water holds out and the air holds out."

Fielden said a lot of the problems will be environmental, the inevitable result of more cars, more trash, more sewage and more strain on a finite water supply.

"We have to deal with the ecology of this desert. If we destroy that, maybe that will be the tipping point," he said.

Right now, such warnings gain little traction, he said.

Like the adage about the weather, everyone seems to talk about growth, but no one ever does anything about it.

"No one has asked how many people this valley can hold and have a good life," Fielden said. "It's too profitable to not ask that."

ALL TALK, NO ACTION?

Outside the heavily regulated enclave of Boulder City, few elected officials have shown much appetite for curbing growth, and high-ranking administrators view the issue as something better left to voters and their representatives.

Asked if she would like to see something done to stem the tide of new residents, Clark County Manager Virginia Valentine said she tries not to involve herself in broad policy decisions such as that.

Pat Mulroy, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and Las Vegas Valley Water District, said continued growth is inevitable, and it's not her job to try to stop it.

Mulroy's only responsibility is to make sure there is enough water for everyone who is here.

"I'm not sure my preference matters. It's not my business to have a preference," Mulroy said.

Clark County School District Superintendent Walt Rulffes offered a similar answer.

"That's outside the province of my position," he said. "I do think there has to be really superlative planning to accommodate another million people. We feel the infrastructure is stretched thin now."

Already, it's taking school buses longer to get to their destinations, and teacher recruitment at schools in poor areas is getting harder as crime and poverty rise in those areas, Rulffes said.

Meanwhile, vacant land for new schools is growing increasingly expensive and scarce.

"We're out there trying to buy property, and it's not as easy as it used to be," Rulffes said.

The district could reach its own milestone in 2019. That's when enrollment is projected to top 500,000 for the first time.

"It's just going to be more of the same. There's going to be major challenges in all areas to keep up with it," Rulffes said.

Since 1994, the district has opened 135 new schools and replaced some or all of the buildings at 11 existing campuses.

District officials recently announced plans to float another 10-year bond issue in November 2008 that could generate $9 billion and build 73 new schools and remodel and expand some aging facilities.

At landlocked schools in older, developed parts of the community, the district could be forced to "go vertical," adding a second or third story to existing buildings, Rulffes said.

TRICKY BUSINESS

Clark County native and longtime Commissioner Bruce Woodbury said he doesn't like how fast the Las Vegas Valley is growing, but feels trying to control it is tricky business.

"Frankly, government has to be very careful with that. Tamper with the market ... and you're liable to screw it up."

Woodbury said he would support a carefully written controlled-growth ordinance, but such a thing would never pass without consensus support from city leaders and the rest of the County Commission.

"That isn't going to happen," he said. "Some of the cities are trying to grow as fast as they can."

The last serious attempt to control growth in the Las Vegas Valley came on Feb. 14, 1991, when the water district stopped promising water for new developments and Henderson followed suit.

Mulroy jokingly refers to the move as the "Valentine's Day massacre."

The freeze on so-called "will serve" letters lasted about 18 months and precipitated the formation of the water authority, which replaced what Mulroy called the "organized chaos" of local water providers fighting each other over the state's Colorado River allocation.

"I can't see us doing that again," Mulroy said. "There has never been a successful case of controlling growth with water."

A more likely approach is "hardening conservation" through higher water rates for high-volume users and larger fines for those caught wasting water, Mulroy said.

She also expects to see further restrictions on "what we allow to be built."

"We can't continue the way we have been going. I've always said it's not whether we grow, it's how we grow," she said. "I think conservation has grown as the need for conservation has required it. It's an evolutionary thing."

That communitywide attitude adjustment has been propelled by seven years of record drought on the Colorado River, which is the primary source of drinking water for the valley.

Earlier this summer, the river's largest reservoir, Lake Mead, shrank to less than half of its capacity for the first time since the 1960s, when water was being held back to fill Lake Powell.

"The growth to me is far more manageable than the consequences of this drought. Far more manageable," Mulroy said.

"If you have a real crisis, it will involve everyone west of the Rockies, and it will be driven by drought."

Ultimately, she said, that could force "a very difficult discussion about land use in the West," where farms and ranches -- not cities -- account for roughly 85 percent of all the water used.

As for talk of Southern Nevada running out of water one day, Mulroy doesn't foresee that happening.

"If the political will is there, the water will be there," she said.

LANDLOCKED BY THE FEDS

One key player in the ongoing development of the region is the federal government, which controls almost 90 percent of the land in Clark County and 86 percent of land statewide.

Since Congress passed the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act in 1998 and significantly amended the law in 2002, almost 40,000 acres have been sold or swapped for development.

An additional 12,568 acres were set aside for schools, parks, conservation areas and affordable-housing developments.

That leaves roughly 27,000 acres of public land available for auction within the federally designated disposal boundary, which extends to the Desert National Wildlife Refuge in the north, Sloan Canyon National Conservation Area in the south, Lake Las Vegas in the east and Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area in the west.

Those 27,000 acres could last for the next 25 years or they could run out much sooner, said Juan Palma, field manager for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management in Las Vegas.

"It all depends on the market. If the market was to pick up tomorrow, maybe all this land wouldn't last," he said.

The largest tracts left, the kind developers like to turn into master-planned communities, are at the northern edge of North Las Vegas and the southwestern edge of Henderson.

None of those prime properties were on the block during the BLM's most recent auction.

Instead, the sale held in November included about 167 acres of mostly small, scattered parcels, many of them south of Blue Diamond Road.

Of the 31 parcels offered, only one found a buyer.

The April 2008 auction is expected to include about 500 acres.

The bureau also figures to play a major part in the development of so-called bedroom communities within a 100-mile radius of the valley.

Palma said additional federal land has been identified for disposal, or could be eventually, in outlying areas of Clark County and neighboring Nye County.

"Clearly, we're going to see a larger Pahrump, a larger Mesquite, a larger Coyote Springs, and probably a larger Laughlin," he said.

There are even bedroom communities springing up in other states and other time zones.

Some residential development has begun along U.S. Highway 93 in northwestern Arizona.

Some predict construction there will accelerate once the new Hoover Dam bypass bridge opens over the Colorado River in 2010, shortening the commute time to Las Vegas.

Meanwhile, back in the valley, Valentine expects to see the limited supply of available land drive "a lot more vertical development."

"I think there will have to be more density," she said. "And I imagine there will be future adjustments to the disposal boundary."

'CHOICES HAVE TO BE MADE'

Even if county leaders decided to clamp down on growth tomorrow, several projects now under way all but guarantee significant population gains for years to come.

At least four new resorts and 45,000 hotel rooms are on track to open on or near Las Vegas Boulevard by 2012.

That could create 278,000 jobs and attract 562,000 new residents to Clark County, according to estimates supplied to the county by consulting firm Applied Analysis.

The largest of the new developments, MGM Mirage's $7.8 billion CityCenter, is expected to produce almost 56,000 jobs and bring in more than 113,000 new residents.

Of course, more people doesn't always translate to more problems.

Consider what happened to the county's air quality between 1994, when the population was 1 million, and today: It actually got better.

According to figures from the Clark County Department of Air Quality and Environmental Management, the county has not exceeded federal guidelines for carbon monoxide pollution since 1998.

Airborne dust levels also have improved. In 1993, federal regulators declared Clark County to be in "serious non-attainment" for particulate matter.

By paving miles of dirt road and working with construction sites to reduce blowing dust, the county reduced its levels of particulate matter to acceptable levels late last year.

Then there are things like flood control and traffic, which are by no means perfect but could be a whole lot worse if not for the efforts of Woodbury and others almost two decades ago.

Thanks to them, Valentine said, the county now has the Las Vegas Beltway and the Regional Flood Control District.

Woodbury said it was clear back then that something had to be done, but it still took a lot of "knocking heads together and getting consensus among people in community."

Similar cooperation and foresight will be needed to address the needs of the county as it races toward 3 million and beyond.

"Choices have to be made," Woodbury said. "Right now, a lot of the choices are being made by people who don't live here. They're being made by people who are moving here for the jobs and by resort developers, some of them local, some of them not."

For Fielden and other advocates of controlled growth, this poses a challenge: How do you engage residents who haven't lived here long and may not plan to stay? How do you start a communitywide movement to curb growth in a place with no strong sense of community?

Fielden insists it can be done, but it will require strong leadership from elected officials and strong support from everyday citizens.

"We're all in this together," he said. "We've got to find a way to start these conversations and find solutions to some of these problems."

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@ reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0350.

RELATED STORY: Residents count blessings, curses of county's growth