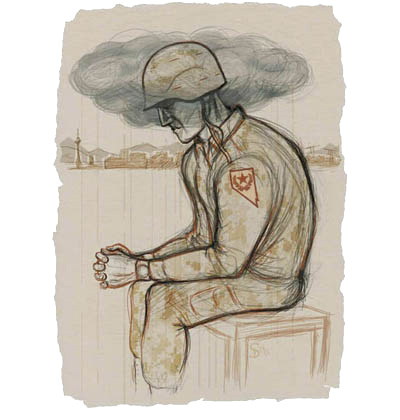

COMBAT’S ‘INVISIBLE WOUNDS’

This is the first in a four-part series.

TODAY: Veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan routinely overcome horrid wounds and loss of limb, but equally formidable foes are the mental effects of head injuries, constant or repeated exposure to danger and making decisions of awesome consequence.

NEXT SUNDAY: When an American dies in combat, the warrior's loss leaves a hole in American hearts.

More than 30 surgeries have helped fix what a roadside bomb in Iraq did to Senior Airman Brandon Byers' body, but nothing can erase the anger, paranoia and flashbacks that sometimes haunt his mind.

His physical recovery from the near-death experience in October 2006 has been difficult.

So has his fight to heal his mental wounds from the battlefield.

"There have been times since I've been back that I didn't want to walk down the street because I was afraid somebody was going to get me," said Byers, who lives with his wife and two children on Nellis Air Force Base. "But I'm not the only one having a hard time, a bad day, or every now and then, a mental breakdown."

Other Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans interviewed by the Review-Journal tell similar accounts of the realities of post-traumatic stress disorder, the psychological offshoot of a life-threatening or traumatic event.

A report earlier this year by the Rand Corp., a nonpartisan think tank, estimates that up to 300,000 recently returned veterans have PTSD or major depression. The report said that only about a quarter of veterans diagnosed with mental health conditions are getting minimally adequate care.

The symptoms of severe PTSD, including extreme anger, flashbacks to a traumatic event, hypervigilant behavior and sleeplessness, can be debilitating and deadly.

Joseph Perez, a Nevada National Guardsman injured during a prison riot in Iraq in 2003, said he became so distraught after his tour that he self-medicated with vodka and painkillers and twice attempted suicide.

"If it'll help somebody else, then I don't mind talking about it," said Perez, a husband and father of three daughters from Logandale, about 60 miles northeast of Las Vegas.

Nationally, nearly 84,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans have been diagnosed with PTSD, said Dr. Antonette Zeiss, deputy chief of mental health services for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

About 1,000 of those diagnoses have come in Southern Nevada, but only a fraction have led to intensive treatment through the VA, said Dr. Ramu Komanduri, chief of staff for the VA Southern Nevada Healthcare System.

Many veterans with mental health problems do not seek any help from the VA, Komanduri said.

"We know many, many veterans don't come to our attention," he said. "Sometimes veterans don't want to seek care. They call it the warrior mentality. ... There's also a lot of denial."

The stigma that keeps some veterans from coming through the doors of the VA could have catastrophic consequences, experts said.

Dr. Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, has warned that "suicides and psychiatric mortality of the current wars could eventually exceed the number of combat deaths," which now are nearly 4,800.

Locally, at least two Iraq and Afghanistan veterans have killed themselves, the Review-Journal found. A third killed himself in Iraq. In each case, the family of the deceased attributed the desperate act to untreated PTSD or depression.

The VA will get about $4 billion in the coming year for mental health and substance abuse services. Though funding is up significantly from previous years, it is roughly the same amount the government spends in two weeks on the Iraq war, according to a congressional analysis.

That concerns veterans' advocates.

"We need to start thinking of the VA as a cost of war," said Elliott Anderson, a Marine Corps veteran from Las Vegas who served in Afghanistan. "People don't think of it that way. They'll put money into the war, but not into the VA."

On top of the skyrocketing cases of PTSD, hundreds of thousands more veterans are coming home with traumatic brain injuries that cause some of the same symptoms as PTSD, according to the Rand study and the Brain Injury Association of America.

The Rand report said that, if untreated, the disorders increase the sufferers' likelihood of unemployment, domestic violence, substance abuse, homelessness and suicide.

Airman Byers, 25, said he feels he is winning his battles against PTSD through treatment and counseling for himself and his wife. He hopes he will be cleared for duty when an Air Force medical evaluation board examines him next year for physical and mental fitness.

"PTSD is real," he said. "It's a big deal, and it's not something that just goes away."

It took the military and medical community a long time to acknowledge that.

Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with PTSD are experiencing what many of their predecessors know all too well. The condition only now has an official name and more acceptance by the government and military.

Persian Gulf War veterans in the 1990s were the first group to return home to a clinical diagnosis of PTSD, paving the way for a generation of Vietnam War veterans to get belated recognition as having the disorder.

In Southern Nevada, the number of veterans of all eras getting specialized care for PTSD has nearly doubled in the past three years, mostly because of an influx of Vietnam veterans in treatment, the VA's Komanduri said.

The military has become more vocal about the "invisible wounds" of war.

Defense Secretary Robert Gates told the government-run Pentagon Channel in October: "People basically say, 'Suck it up and get on with the job' ... without realizing that people who have PTSD have suffered a wound, just like they've been shot, and need to be treated."

But public institutions are still wrestling with how to deal with PTSD.

Earlier this year, a VA supervisor in Texas discouraged psychologists and social workers from diagnosing veterans with PTSD out of concern over a proliferation of "compensation seeking veterans," according to an internal VA e-mail obtained by the nonprofit Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington.

But the VA's Zeiss said several characteristics of the current wars have increased the chances that veterans will be diagnosed with mental health disorders.

"The extended deployments and multiple deployments and the nature of the violence people are experiencing are creating stressful situations that lead to a range of problems," Zeiss said.

The postwar emotions of this batch of combat veterans are not unique, but they might be more extreme, agrees Larry Ashley, a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas who has advised the Army on PTSD and addiction issues.

Ashley, a Vietnam veteran, said unconventional warfare methods in parts of Iraq and Afghanistan create constant danger that makes for postwar mental health issues, as does deployment of so many National Guard and Reserve troops.

"When folks from the National Guard and reserves get back, how do we phase them back to the civilian environment?" he asked. "The military hasn't always done a good job of doing that."

Some veterans and active-duty soldiers wonder whether their chances for promotion will be hurt if they seek mental health treatment.

Ashley said problems on the job or at home can send veterans with mental health problems into a downward spiral, especially if they are not getting treatment or counseling.

Perez, the Nevada National Guard military policeman hurt in Iraq, said part of his problem readjusting to civilian life stemmed from the feeling he was being "thrown back into society."

The Guard is trying to address that complaint.

Perez's unit, the 72nd Military Police Company, which has deployed twice to Iraq, recently set up a reintegration team to help soldiers cope with returning home. The program was created out of necessity, 1st Sgt. Jacob Gonzales said.

"We have some horror stories," he said. "There wasn't a support network for them. ... We had a lot of divorces, alcohol problems and gambling problems."

Hal Woomer, Nevada National Guard state chaplain, said he helps veterans having trouble adapting to being back home.

"Not all the skills they used in the theater will help them thrive in civilian life," he said. "Some soldiers come back without any issues, but some have problems readjusting."

Overcoming the disconnect between military experience and civilian life is a big challenge, said Shalimar Cabrera, program director for the nonprofit U.S. Veterans Initiative in Las Vegas.

"When vets come back, they try to lead a normal life, even when they have changed," she said. "PTSD is talked about more, but a lot of young veterans don't want to believe they have it."

UNLV's Ashley said veterans should not hesitate to follow the lead of Carter Ham, a four-star Army general and former commander in Iraq, who recently spoke publicly about getting PTSD counseling from a chaplain.

"That's really significant," he said. "We have to do more to remove the stigma. ... We need more leaders who'll say, 'I've had some rough spots, but I'm moving forward.'"

Locally, help soon will be easier to find. A new $600 million VA hospital in North Las Vegas, with 90 inpatient beds, is expected to be completed by 2011. Currently, VA services are scattered throughout the area.

Dana Harbaugh, a Gulf War veteran, said he hopes this generation of war veterans does not make the same mistake he did.

Harbaugh said he did not seek PTSD treatment until he hit the skids in the late 1990s. By that time, he was on the streets and in and out of a VA hospital in San Diego with alcohol poisoning.

"When the VA diagnosed me with having combat PTSD, I still didn't want to believe it," Harbaugh said. "But when I finally got help for it, it was the best thing I ever did."

Contact reporter Alan Maimon at amaimon@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0404.

ON THE WEB Online interactive VETERANS SERVICES CONTACTS Nevada Office of Veterans Services (south office) 950 W. Owens Dr. Room 111 Las Vegas, NV 89106 (702) 636-3070 www.veterans.nv.gov Nevada Office of Veterans Services (north office) 5460 Reno Corporate Dr. Reno, NV 89511 (775) 688-1653 www.veterans.nv.gov VA Southern Nevada Healthcare System 901 Rancho Lane Las Vegas, Nevada 89106 (702) 636-3000 www.lasvegas.va.gov Wounded Warrior Project (877) 832-6997 www.woundedwarriorproject.org