Crime lab gives police boost

DNA evidence has helped crack murders, rapes and other heinous crimes in the Las Vegas Valley for years. Now it's helping police solve run-of-the-mill house break-ins and car thefts.

Thanks to a boost in manpower and upgraded equipment in the past 12 months, the Metropolitan Police Department crime lab has eliminated its DNA case backlog and turned its resources toward property crimes. Department leaders hope the move will put burglars and car thieves behind bars for crimes that are traditionally difficult to solve.

Lt. Robert DuVall, who oversees the agency's auto theft and burglary units, welcomed the scientific firepower. His detectives have gotten about a half dozen DNA hits on stolen car cases in the past month alone, and each one helps identify a suspect or make a case stronger, he said.

"I love any tool that helps catch thieves," he said.

Investigators have used DNA analysis to make cases for more than a decade, but limited staffing and time-consuming scientific testing meant property crimes took a back seat to murders and rapes. Advances in technology have shortened the time needed to process DNA samples, but many crime labs must still deal with a lack of scientists to conduct the tests.

"In general, property crimes just sit there in the backlog," said Bill Marbaker, past president of the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors.

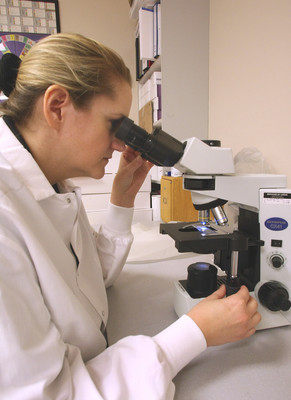

That had been the case at the Las Vegas police lab, which had just four DNA analysts in early 2006. Now it has nine, as well as four administrative employees who can conduct DNA tests if needed, lab director Linda Krueger said.

The lab also recently added a DNA testing machine that can process 16 samples in about 40 minutes, more than quadrupling the testing capacity of its old machines. A second 16-sample machine, which costs about $150,000, will soon be purchased with a federal grant.

Another federal grant paid to process about 4,600 backlogged DNA samples from Nevada felons and enter them into the national DNA database.

With the elimination of the backlog and the added manpower and processing capacity, the lab turned its resources to property crimes.

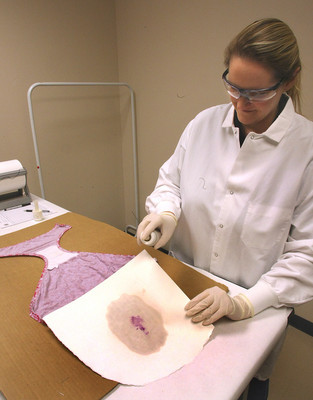

In April, the lab started a pilot program by testing about 60 DNA samples taken from burglary scenes, such as blood, saliva and other bodily fluids. The initial results were promising, with five of the first nine samples getting hits in the national database.

Since then, the lab has tested samples from burglaries going back to June 2006 and found 28 hits in the national database for convicted criminals and 11 hits for other crimes, Krueger said. The lab is now looking at samples going back to January 2005.

Crime scene investigators are also collecting DNA evidence at new crime scenes. They won't respond to every burglary, but they'll be sent to loctions where they have a good chance of finding fingerprints or DNA evidence, said Lt. Chris Jones, who heads the CSI unit.

With the help of a National Institute of Justice grant, Denver and several other cities undertook similar burglary DNA projects in 2005. DNA matches helped Denver police make several high-profile arrests of serial burglars, and the city's burglaries dropped 11 percent from 2005 to 2006. 2007's numbers are on pace to drop even further.

DNA testing for property crimes also helps fight more serious crimes because many criminals who break into homes or steal cars are also committing rapes and murders, according to a 2004 report by the National Institute of Justice.

A St. Louis rape case two years ago illustrated the point. One man confessed to the rape and baseball bat beating of a young woman, but DNA testing cleared him and pointed police toward another man who submitted his DNA for a conviction on forgery and auto tampering.

Las Vegas police hope to see similar results as more DNA samples are tested and entered into the database.

Police have also started a system that allows crime scene analysts to fast track property crime evidence to the lab. Under the old system evidence didn't go to the lab until a detective requested it, usually at least two or three days after the crime.

Now, crime scene analysts who recognize a burglary trend, for example, can request lab processing themselves and cut a few days of lag time.

The system is part of Sheriff Doug Gillespie's intelligence-led policing initiative, which looks to technology and new ideas to fight crime. Response to the new system has been positive, he said.

"You show any cop a scientific process that works and helps solve crimes, they're all for it," Gillespie said.

Contact reporter Brian Haynes at bhaynes@reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0281.