DEATH IN DESERT AIR

On the morning of April 21, 1958, Faith Paris dropped her husband off in the parking lot of Los Angeles International Airport. She had their three young sons with her, so she couldn't go inside to see him off.

Air Force Capt. Steve Paris, 32, leaned into the back seat and told the boys, "Be good for your mom. I'll be home tomorrow night."

A little over an hour later, the United Air Lines flight he was on collided in midair with a fighter jet from Nellis Air Force Base, and both aircraft plunged 21,000 feet to the Las Vegas Valley below.

The two men in the jet and all 47 people on the airliner were killed.

Fifty years later, it remains the worst air disaster in Las Vegas history.

A metal cross lashed together with yellow twine marks the spot where the United DC-7 slammed into the ground and exploded.

Back then, the crash site was an empty patch of desert several miles from the nearest paved road. Now it is a trash-strewn lot between a Bank of America and a neighborhood bar on Cactus Avenue just west of Decatur Boulevard -- an area soon to be swallowed by Southern Highlands.

It would probably be a housing tract or a shopping center already, but the owners of the parcels never came together on a project.

Whatever becomes of the property someday, those touched by the crash would like to see a permanent marker placed there.

Shirley Suson, now 82 and living in Denver, lost her parents on United 736. She thinks Dave and Edith Lipson, who were in their late 50s when they died, deserve to be remembered along with everyone else killed that day.

"I think about them all the time," she said. "That mother of mine was adorable, and she loved children. She would have adored all of mine."

Local aviation historian Doug Scroggins has been pushing for some type of memorial at the site since the 40th anniversary of the disaster.

"There needs to be something erected out there. Something needs to be done," said Scroggins, who has studied the crash extensively.

Since pinpointing the mostly forgotten impact site in 1997, he has visited the area dozens of times in search of remnants. The brush and dirt have yielded several pairs of novelty pilot wings that flight crews would hand out to children and fragments of dishware stamped "UAL."

Denver resident Mark Paris, Steve's oldest son, also found aircraft debris when he went to the site in 1999 to put up the metal cross. He says the place deserves recognition as a historical site.

"This crash was pivotal in American military history," he said.

Mark Paris, 57, began researching a book about the tragedy in 2000.

Paris said he went into it hoping to learn the definitive story of that day and what happened to the victims' families in the years that followed.

Instead, he found intrigue.

Paris said 13 people on the airplane, his father included, were involved in the development of the country's intercontinental ballistic missile arsenal, "the most top secret project in the country at the time."

His father was one of four people on the flight with briefcases handcuffed to their wrists, he said.

Never before had so many people tied to the missile program flown together in the same aircraft, a fact that did not go unnoticed by some of the men in the group, Mark Paris said.

Before they boarded, seven of the defense workers, Steve Paris included, bought $100,000 life insurance policies that were sold at airports back then.

"He never did that," Mark Paris said of his father.

After the crash, FBI agents showed up to secure the wreckage of the airliner.

"They were not looking for survivors. They were looking for papers," Faith Paris said.

"This hurt America in a real nasty way that people didn't hear about," Mark Paris said. "This put the ICBM system on its ear for a while."

He is now convinced that the crash of United 736 was no accident, and he claims to have proof of a plot -- several plots, actually -- involving the KGB.

If you want to read more about that, though, you will have to wait for Mark Paris' book. No publication date has been set.

The official accident report by the Civil Aeronautics Board, precursor to today's Federal Aviation Administration, gives no hint of conspiracies.

It blames the crash on the high rate of speed at which the aircraft came together, too fast for the pilots to react in time.

Though the sky was clear and visibility excellent that morning, the pilots apparently did not see each other until it was too late. Investigators chalked that up to a failure of Air Force flight rules to account for "the human and cockpit limitations" of trying to see and avoid other aircraft while traveling at near-supersonic speeds.

United 736 was destined for New York with scheduled stops in Denver, Kansas City, Mo., and Washington, D.C.

Steve Paris was slated to get off in Denver and catch another flight to Strategic Air Command headquarters in Omaha, Neb.

Dave and Edith Lipson were headed home to Denver after visiting their son, Albert, in Southern California.

The flight was half full when it departed LAX at 7:37 a.m.

Eight minutes later, an F-100F Super Sabre took off from Nellis with a student pilot in one seat and an instructor in the other.

At 8:30 a.m., the paths of the two aircraft intersected nearly head-on nine miles southwest of where McCarran International Airport is now.

Investigators determined that the fighter jet veered at the last moment but couldn't avoid the collision. It struck the right wing of the prop-driven airliner, sheering off a 12-foot section near the tip.

Several Las Vegas residents who saw the impact reported a puff of smoke, a flash of fire, and a shower of metal pieces.

As the burning airliner spiraled toward the ground, its engines were sheered off by the force of the descent.

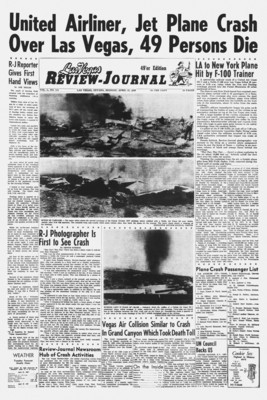

In a Review-Journal report the day after the crash, one eyewitness said the aircraft was "a spinning ball of fire which exploded intermittently as it snaked toward the earth."

Scroggins can't help but think of the pilots of the doomed flight.

"I can imagine what these guys went through. They fought this thing every way they knew how. It was impossible," he said.

The fuselage of the DC-7 slammed into the ground half a mile from where the engines landed. The Super Sabre crashed and exploded five miles south, where the Union Pacific railroad tracks loop past Sloan.

Faith Paris was just home from LAX, hanging clothes to dry, when the news bulletin came over the radio.

She "didn't hear another word from anyone" until several hours later, when a car pulled up outside the house and a military chaplain got out.

"I knew right then that was it," said the 79-year-old who lives in Denver, about 20 miles from Suson. "I was so mad at Steve and at God. And I was scared. I was scared to death.

"It took me a few years, but I got over it," she said.

Suson was working for United Air Lines at its office in Washington, D.C., when the news came in about a plane crash in Nevada. A short time later, her supervisor called her into his office to tell her that her parents were among the dead.

"They were flying (for free) on my pass," she said. "That was one of the perks" of the job.

"My mother was afraid to fly. I would say, 'Oh, mom, it's like sitting in your living room.' You don't think that plays over and over and over in my head?"

Within days of the crash, two pilots for other airlines reported near-miss encounters with F-100s that were "stunting" over Las Vegas.

Back then, Suson said, the crews on domestic flights frequently complained about military aircraft flying too close and treating them like targets.

In his book "From Takeoff at Mid-Century: Federal Aviation Policy in the Eisenhower Years, 1953-1961," Stuart I. Rochester notes that Nellis was one of the busiest jet-fighter training bases in the country, but it operated independently from commercial air traffic control despite its location beneath a major east-west airway and frequent near-miss reports in the area.

According to Rochester, Aviation Week declared the Nevada crash "a ghastly exclamation point in the sad story of how the speed and numbers of modern aircraft have badly outrun the mechanical and administrative machinery of air traffic control."

The disaster swiftly led to changes in the way airspace was allocated to commercial and military flights, and ushered in widespread improvements in air traffic control overall.

In August 1958, President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aviation Act, which specifically referenced the crash of United 736 in ordering the creation of the FAA.

"They (military aircraft) can't hotdog over here anymore," said Scroggins, who owns an aircraft parts and salvage business in Las Vegas. "All the airspace is really well-watched now."

The crash also prompted the military, defense industry and some large corporations to adopt rules to keep groups of technical people from the same critical project from traveling on the same aircraft.

"That's the last time sensitive information and that many personnel with (knowledge of) sensitive information ever flew on the same airplane," Mark Paris said.

Faith Paris has made four visits to the crash site since Scroggins first took her there in 1997.

"I never knew where he died," she said. "I needed to see that."

She has been talking to politicians and trying to get a memorial built for Flight 736 ever since.

With any luck, she said, news of Monday's 50th anniversary will finally make that happen.

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.