Decade of drought leaves two lakes, Powell and Mead, in same boat

When the lake shrank to a historic low, it sent marina owners scrambling to keep their operations afloat and prompted jealous grumbling about how much water there was in the reservoir next door.

Things have gotten much better at Lake Powell since 2005.

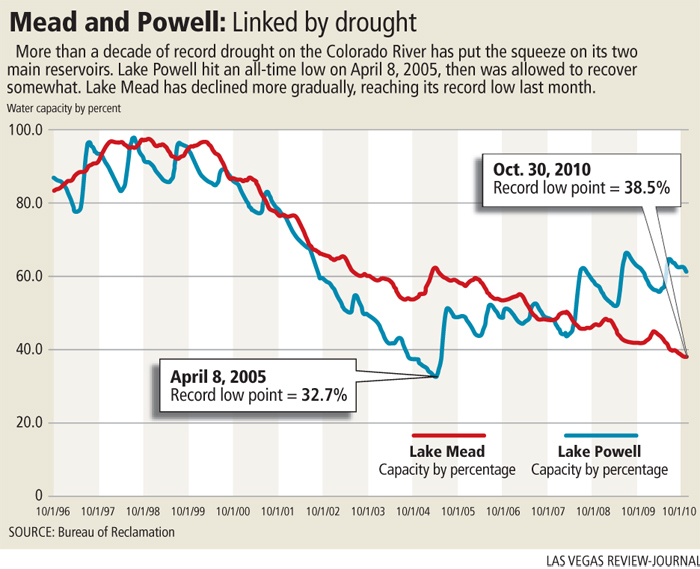

Today, it's Lake Mead that hovers at about 38 percent of capacity -- an all-time low -- while Powell is better than 60 percent full.

The reversal of fortune for the twin reservoirs has prompted some of the same grumbling -- and even a conspiracy theory or two -- this time from farther down the Colorado River.

Soon, though, Lake Mead may get a little help from its upstream neighbor, thanks to a joint operating regime that was developed for the two reservoirs after Powell's record drop five years ago.

Federal forecasters now say it is likely that Lake Mead will receive a larger than usual release of water from Lake Powell in the coming year, as conditions in the two reservoirs approach a trigger point for so-called "equalization."

The extra water for Lake Mead -- 9 million acre-feet instead of the standard 8.23 million acre-feet -- could raise the level of the reservoir by 7 feet or more and delay an unprecedented shortage declaration that would require Nevada and Arizona to cut their river use.

The complicated framework that now decides the coordinated rise and fall of the nation's two largest man-made reservoirs was implemented in late 2007. The rules are designed to protect minimum water levels in lakes Mead and Powell through the year 2026.

"The idea was to better share the gain when the flows are good and share the pain when the flows are not so good," said Terry Fulp, deputy regional director for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's Lower Colorado River office in Boulder City.

They also wanted to provide as much predictability as possible to all the people who depend on the famously fickle Colorado River.

Fulp headed the team that wrote the operating regime. It was a painstaking process that required them to draw up hundreds of different scenarios and feed them through intricate computer models to see how each might work, he said.

The team also had to weigh the often divergent interests of water managers, power customers, marina operators, river runners and conservationists looking to protect sensitive species in the Grand Canyon.

And while the end result doesn't always seem fair to people standing on the shrinking shore of one lake or the other, water officials insist it is working as designed.

Southern Nevada Water Authority chief Pat Mulroy said river users are "just buying time," trying to outlast what already ranks as the worst drought of the last century.

The coordinated operation of Mead and Powell is just another stall tactic, she said.

"We are living on our savings account," Mulroy said, and that account has been significantly drained over the past decade.

In 1999, lakes Mead and Powell were close to full.

Today, the combined storage in the two reservoirs stands at about 55 percent of capacity.

"Think about it cumulatively. Without Powell, there would be no Mead right now," Mulroy said. "You've lost a reservoir."

Roughly 90 percent of the Colorado River's flow begins as snow that collects in the mountains of Colorado, Utah and Wyoming from November to late May, when it begins to melt and flow downstream.

Powell swells with that water in early summer, rising sometimes by a foot or more a day.

Lake Mead follows the opposite pattern, filling through late fall and winter with releases from upstream and dropping during the late spring and summer when water demand peaks at farms and cities fed by water released through Hoover Dam.

"It's really a demand driven operation at Lake Mead, whereas Powell is really a supply driven operation," Fulp said.

Of the seven states that draw from the river, Nevada receives the smallest share but depends on it more for municipal use than anyone else.

Nearly all of the 300,000 acre-feet Nevada gets annually goes to the Las Vegas Valley, where it accounts for roughly 90 percent of the drinking water supply.

One acre-foot of water can supply two average valley homes for a year.

Since the drought took hold in 1999, the surface of Lake Mead has plunged 130 feet to a level not seen since it was being filled for the first time in 1937.

Right now, Mulroy's agency is racing to complete work on a new intake pipe at Lake Mead that will allow water to continue to flow to Las Vegas should the water level fall another 30 feet.

But as bad as things are at Lake Mead, it still hasn't reached the depths to which Lake Powell sank in 2005.

On April 8 of that year, with Lake Mead still comfortably above the 60 percent mark, the reservoir straddling the Utah-Arizona border dropped to 32.7 percent of capacity. That was its lowest level since it was filled behind Glen Canyon Dam for the first time in the 1960s.

"I can remember it was really tough on the concessionaires because they had to keep moving their marina facilities," said Max King, chief of interpretation for Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. "They were working from dawn to dusk chasing the water and trying to keep things afloat out there."

During that time, Lake Powell shrank by about 40 miles, from a "full pool" length of 186 miles to less than 150 miles long.

The water dropped so much that Hite, the reservoir's northernmost marina in Utah, was forced to move because the lake there reverted to a river.

The marina operators have not returned to Hite, and King doubts they ever will.

He said there was one complaint he heard a lot back then: "Why do we have to keep sending all that water down there? Why can't we keep it here?"

Fulp is getting similar questions these days about Lake Mead.

People wonder why the two reservoirs can't be kept at the same level or why Powell doesn't simply send down some extra water now to bump Mead up a foot or two.

The surface of Lake Mead now sits about 1,082 feet above sea level, just 7 feet away from the trigger point for a 13,000 acre-foot reduction to Nevada's share of the Colorado River and far deeper cuts for Arizona.

A drop to elevation 1,075 at Lake Mead also would trigger a vote by the Southern Nevada Water Authority board on whether to build a pipeline to tap groundwater across eastern Nevada.

That's where the conspiracy theories come in. Some have suggested that Mulroy is using her influence to keep Lake Mead artificially low and force the decision on the pipeline project.

Fulp called that "nonsensical."

Mulroy called it "the dumbest thing I've ever heard."

"We're going out of our way to keep extra water in Lake Mead," she said. "The last thing we want is a shortage. Our single biggest goal is to keep as much water in Mead as possible to avoid that shortage declaration."

So why is Mead so much lower than Powell?

The drought, for one thing. And all those complicated and heavily negotiated rules and triggers hashed out by Fulp's team in consultation with stakeholders up and down the Colorado.

But here's a far simpler answer, albeit one unlikely to bring much comfort to frustrated boaters and marina operators facing more expensive low-water work:

"It's our turn right now," Fulp said.

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.