Detective monitors missing persons cold cases for Las Vegas police

The grainy footage opens on an abandoned parking lot that borders the desert at the southwestern edge of Las Vegas.

For several seconds, nothing but some frail-looking trees swaying in a light breeze.

Then a taxi appears and stops at the side of the parking lot. Out steps a man, his features fuzzy in the security video.

He stands at the side of the lot for a while, maybe waiting for the taxi to drive away, then slowly walks toward the desert. He zigzags across the camera's field of vision several times, growing more distant with each turn, finally disappearing into the horizon.

The whole scene takes about three minutes on a spring afternoon in 2007.

The man hasn't been seen since.

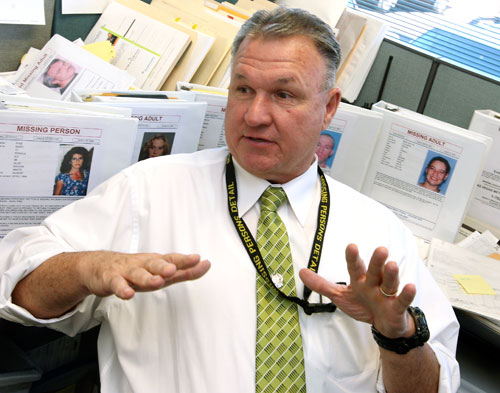

His is one of scores of cases that have landed lately on the desk of Detective Dan Holley, who in June took charge of the Metropolitan Police Department's new missing persons cold case unit. The one-man unit's mission is to solve, or at least update, roughly 600 cold cases at least 60 days old.

The 27-year department veteran, who has worked in the missing persons division several years, believes his new assignment might be unique.

"There are tons of cold case homicide units," he says. "But I think we may have the only missing persons cold case detective in the country."

Holley, 54, now spends his days leafing through old case files, following up on abandoned leads, reinterviewing family members and friends of adults who have gone missing in Las Vegas.

(Missing children's cases, he explains, don't go cold. Detectives never stop actively working them.)

At the very least, he inputs information about the missing into the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, NamUs, a clearinghouse for missing persons and unidentified decedent records.

It's safe to say Holley might never completely catch up.

Turns out Vegas is a very popular place to disappear. About 1,000 people go missing here each month. The cases are divided among 12 detectives in the missing persons' bureau.

For every case Holley reviews, many others grow cold.

But the majority of new cases are quickly solved when the person in question resurfaces. They might have fought with a spouse, for example, and didn't feel like coming home for a day or two. They might have gone on a binge and holed up in a cheap downtown motel. Plenty of people come to Las Vegas for adventure and fail to check in at home.

"Maybe they don't have colored light bulbs in Kentucky or Ohio," Holley says. "Maybe they never stay up past 6 p.m. They come here, stay up all night, play poker and don't call their mom. It's great to come visit, but folks need to call their flippin' mom."

Plenty of missing persons cases also involve people who, turns out, don't particularly want to be found. Detectives wind up getting stuck in the middle of family squabbles.

"I'm constantly getting yelled at by parents who want to be in control of their adult children," Holley says. "The kid will say, 'My mom wants to control my life!' The mom will say, 'You tell him to call his mother!' "

Trouble is, if adults want to stay missing, that's their right. And Holley can't tell their family exactly where to find them. He can't tell the family anything at all beyond, "Your kid is alive and well."

"You have the right to fall off the face of the Earth if you choose to," he says.

Holley and his co-detectives have located "missing" family members "every way you could imagine," he says. At a bar in Rachel, for example. At a boyfriend's house. In Germany.

"They even get deported," he says. "Or pretend they got deported because they don't want their boyfriend or girlfriend to know they were really off with someone else. Or they don't want their boss to know the real reason they didn't show up for work."

Those are the easy cases, and detectives quickly move on. Much tougher are those in which someone is legitimately missing and might be in danger. In such cases, "we don't sleep until we find the person," Holley says.

But sometimes they don't, until it is too late. Such was the case of Jodi Brewer, a 19-year-old who disappeared from Las Vegas in August 2003. Her torso was found later that month in the desert near an Interstate 15 offramp south of the Nevada-California border.

Such cases haunt detectives whose mission is the preservation of life, Holley says. A grim part of his job involves determining whether any of Las Vegas' cold cases match unidentified remains found elsewhere in the country. More than 4,000 such remains are found each year, and there are 40,000 sets of remains that are still unidentified, he says.

On a more positive note, Holley's new job affords him the luxury of pursuing whichever cold cases he finds most intriguing each day.

On this morning, those cases include that of Trevor Morse, the 30-year-old man whose disappearance into the desert was captured by a security video camera behind a furniture store, and that of Opal Parsons, an 81-year-old woman who went missing from her home near Charleston and Nellis boulevards in August 2007.

Holley once fielded a call from a psychic about the Parsons case, he says. She was convinced Parsons is stuck in the trunk of a white Chevy Corsica parked by a gravel pit in Kentucky and is "mad as hell" that she hasn't been found.

"I told her, 'Tell Opal to hop out the car and give me a license plate number,' " Holley says cheerfully. " 'Tell Opal to hook me up.' Psychics are full of beans."

A couple months ago, Holley's interest was piqued by a collection of missing persons cases of a different sort: five adults under county guardianship who don't know who they are. He read about the cases in the Review-Journal. The five, who all suffered from mental illnesses or injuries that left their memories impaired, weren't physically missing; their identities were.

Holley went to work immediately and has so far managed to identify three of the five wards, in the process reuniting one woman with the family who had searched for her for seven years.

The two remaining wards are a man known as Earle Trauma, thought to be between 40 and 50 years old, who was hit by a car and suffered serious brain injuries in February 2008; and a 50- to 60-year-old woman who believes her name is Diana English. English suffers from schizophrenia and has been in the custody of Clark County almost a decade. Officials have been unable to verify her name by linking it to any records.

Holley continues working both cases when he has time, and he might be close to identifying English. Earle Trauma remains a complete mystery. At one point Holley thought Earle Trauma could be a man on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted list for killing his wife and two young children in Arizona in April 2001. But the fingerprints didn't match.

"It just kind of eats away at you," Holley says. "Who the heck are these people?"

Holley daily asks himself a similar question about his other cases: "Where the heck are these people?" And he plans to keep searching until he has the answer.

The most valuable lesson Holley has learned through the twists and turns of hundreds of cases, the majority of which turned out to involve people who weren't truly missing, is, "We don't know people."

"That's the one thing we do know," he says. "People are odd."

Contact reporter Lynnette Curtis at lcurtis@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0285.