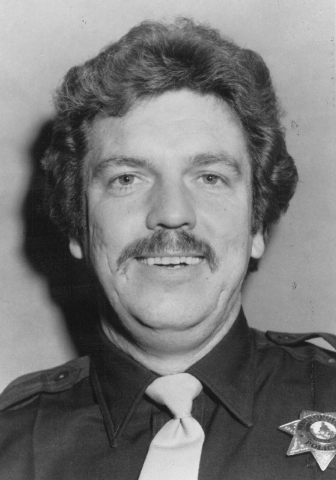

Ex-constable cheerfully tackles next challenge

Robert Gronauer was ready to celebrate.

Surrounded by dozens of supporters that hot June night three years ago, the man better known as Bobby G. settled in to watch the incoming primary election results in his race for Las Vegas constable.

They expected an easy win.

For a dozen years the popular incumbent efficiently had handled the obscure office’s unglamorous duties of serving legal papers and carrying out evictions. After years of turmoil surrounding the office, he had taken over, restored its reputation and made money, not headlines.

But as results rolled in that night, Gronauer’s characteristic optimism turned to disbelief, then disappointment. The popularity and effectiveness that had carried him to election victories before wouldn’t be enough this time.

Maybe he hadn’t campaigned hard enough. Maybe it was the mistake with his campaign mailers, which landed in far fewer mailboxes than intended. Maybe voters mistook the victor — John Bonaventura — for his well-known cousin, Las Vegas Justice of the Peace Joe Bonaventure.

In the end maybes didn’t matter. The voters had spoken, and it hurt.

“I got a claw in my stomach for three weeks,” he says.

Since then Gronauer has said little about that night and even less about his successor’s headline-grabbing controversies, including a profanity-laced foray into reality television, sexual harassment allegations and lawsuits from former staffers.

He says he isn’t bitter and doesn’t want to come off so.

“You’re only entrusted to that office for a certain number of years,” he says. “You take care of that baby, you nurture it. It wasn’t my office. It belonged to the people who elected me.”

And now it was in someone else’s hands.

Back at home after his election night defeat, Gronauer hugged Cathy, his wife of more than three decades.

“I’ll figure something out,” he told her.

He would start over, something he’d been doing his whole life.

FOG OF MEMORIES

Gronauer was born Robert Gandi in Wilkes-Barre, Pa. in 1947. This much he knows.

The rest of his childhood is a fog of memories and a history cobbled together through research and the faded recollections of relatives.

He was 3 months old when his father was shot and killed in the bar he owned. Police called the death a suicide, though Gronauer has his doubts. Another man was in the bar, “not a nice guy” who went on to marry Gronauer’s widowed mother.

Gronauer later became a ward of the state — family members told him it was sometime after his stepfather tried to drown him. He bounced between foster homes until he was 13, when a coal miner and his wife adopted him. They changed his name to Robert Gronauer, the name of the teenage son they had lost in a house fire. He believes he was their “replacement child.”

It was a fresh start for Gronauer, but the new family came with its own problems.

Gronauer’s adopted mother was an alcoholic, he says, who threw rocks at him and “told me to go back where I came from.” And his parents expected him to pay rent and buy his own clothes. He went to work before and after school in a bakery where he scraped floors by hand.

“They gave me a hell of a work ethic,” Gronauer says of his adoptive parents. Otherwise, “they didn’t make my life any better or worse.”

Decades later in a meeting with his biological mother, Gronauer expressed gratitude, not bitterness.

“She was a frail old lady sitting in a corner,” he says. “I knelt down by her and said, ‘Mom, I’m Bobby.’ She started crying really hard. I told her, ‘You have nothing to be ashamed of. Things worked out well for me.’ ”

The rocky start would shape him for the rest of his life. Because of it, “there’s nothing you can give me I can’t handle,” he says. “You give me a challenge, I’m going to get it done.”

BLOOD STRIPES

Gronauer was fresh out of high school and ready for life when he got his first piece of mail ever — a draft notice.

He stopped by the local Marine Corps recruiting office one day in 1966, hoping to join the branch of his choice.

“I never saw a Marine in my life,” he says. “God, he was the prettiest thing. It looked like such an honor to wear that uniform.”

Gronauer enlisted. Soon he shipped off to Vietnam as a Marine Corps private. He came back the next year a sergeant.

“It’s called blood stripes,” he says.

By his count he survived 16 firefights, and a bullet to the face. He saw a lot of people die. He received the Purple Heart and a Bronze Star for valor, something he still can’t comprehend.

“I have medals that say I’m a hero,” he says. “I lived and I’m the hero? I get to understand love. I get to understand life. I get to see children raised.”

After his tour, Gronauer returned to Pennsylvania, quickly married and started a family. At the urging of a family friend, he became a police officer in Baltimore.

He loved the job and the gritty Baltimore neighborhoods he patrolled. As a beat cop, Gronauer drew from his experience in Vietnam.

“It taught me how quick life can be taken away with no warning, no rhyme or reason,” he says. “So while you’re here, be involved, make the most positive impact you can.”

COMING HOME

Gronauer was a police union leader when officers went on strike five years later. He was forced to resign over it, he says.

At the same time, his marriage crumbled, he says. He lost his wife and two young children. Divorced and broke, he decided to make another fresh start.

With a test date lined up for a policing job in Phoenix, he hit the road in 1974.

But a good-looking blond hitchhiker in Tennessee sidetracked the freshly single Gronauer.

“We struck up some good conversation and a lot of good other stuff,” he says.

He drove her home to Hondo, Texas, where he stayed a little longer than he should have, he says.

Gronauer got to Phoenix too late for the test and out of luck. With $23 left to his name, he rented a cheap motel room, nodded off and awoke with an epiphany.

He would go to Las Vegas, where he figured “a boy can be a man in a hurry, and a man can be a boy in a hurry.”

He was flooded with hope as he steered over the mountain and saw Sin City before him.

“I love this place,” he thought. “I’m not going anywhere else.”

But he had no prospects. For weeks he lived out of his car, parked on Fremont Street in front of the El Cortez, getting hassled nighty by the cops.

Then the Metropolitan Police Department offered him a job as a corrections officer. Two years later he was a beat cop again.

The patrol car “felt like a well-fitted glove,” Gronauer says.

PROUD MOMENTS

Gronauer spent 24 years on the force, becoming known for his charm and for making a difference in troubled neighborhoods.

He was named one of the nation’s top cops for his work in Gerson Park, a gang-infested West Las Vegas housing project where he and six officers set up shop. They befriended neighbors, started a job-referral service for teens, even launched a Boy Scout troop.

“He was a great street cop,” says Clark County Sheriff Doug Gillespie, who trained under Gronauer in the early 1980s. “Bobby had a real knack for talking. Boy, he could get information out of people by talking that even today I marvel at.”

Gronauer considers his career with the department a collection of proud moments.

“When you find a lost child. When you get a lady to the hospital in time to have her child. When you save a person’s life. When you give somebody peace before they die.”

But he knew when it was time for a new challenge. He was getting older, he says, and it got harder to “chase these kids” on the street.

A self-described “fixer,” Gronauer searched for a new project. He chose the constable’s office in part because “it was always in trouble.”

The office’s checkered past included reports of a constable who worked half-time for a full-time salary, of meetings in topless bars and of the former constable selling deputy badges for campaign contributions. The office was a money-losing venture.

Gronauer set about cleaning things up when he took office in 1999. By 2002, the office was generating a $500,000 annual profit. At the end of Gronauer’s third term, it was roughly $7 million in the black.

“We grew it from nothing to something,” he says.

But then came that unexpected election-night loss, and with it the need to start over yet again.

THE NEXT NEW START

Today, the silver-haired Gronauer, 66, runs a thriving private investigation business specializing in disability and worker’s compensation fraud cases.

“There’s money in the bank and everybody’s getting paid,” he says.

But he admits he misses the constable’s office and hates to see it hemorrhaging money and courting controversy.

“It hurt to see the wheels come off,” he says.

His blue eyes sparkle when he considers the possibility of some day “fixing” the office again, despite the fact that county commissioners have voted to abolish it come 2015. They got rid of the office once before in 1993, but resurrected it two years later.

Commissioner Tom Collins says it’s possible the office could eventually return. “That’s the politics of it.”

Another possibility would be to make the constable an appointed position under the sheriff. Gronauer would be the perfect fit, Collins says.

“He ran that office professionally,” he says. “He’s the kind of guy who could be sheriff, governor, mayor or anything.”

Gillespie says if his office winds up assuming constable duties, he’ll consider “putting someone over there to oversee day-to-day operations. You bring together people with experience, like Bob Gronauer.”

For now, Gronauer is focused on building his new business. But he figures sooner or later he’ll be looking for his next new start.

“There’s something else out there for me to accomplish,” he says. “I’m still looking for whatever that is.”

Contact reporter Lynnette Curtis at lcurtis@review journal.com. Follow her on Twitter @lynnettecurtis.