JIM ROGERS AND HIS MONEY TALK

Jim Rogers' vow last month to cut off gifts to Nevada's university system has cemented his reputation as the nation's most unconventional chancellor.

Rogers is the first to admit he owes his position to the vast amounts of money he has made, and given away, over the years.

But money, whether spent on education or politics, hasn't always bought acceptance.

It's been a rocky year for the state higher education system's chief executive and largest benefactor, who of late has become a bigger player in financing political campaigns.

First came a brief resignation in January prompted by anger over criticism from a university regent. Other spats with regents followed, the most recent leading to Rogers' decision to take future donations elsewhere.

The announcement was another audacious move from a man who speaks loudly with both voice and pocketbook.

"There really hasn't been anybody like him in any university system," said Rich Novak, executive director of the Center for Public Trusteeship and Governance at the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges.

"His considerable wealth makes him unique. ... What's happening there is so unusual. Only in Nevada."

Rogers, who turned 69 on Saturday, estimates he's contributed or pledged $275 million to universities, including about $60 million to institutions in Nevada.

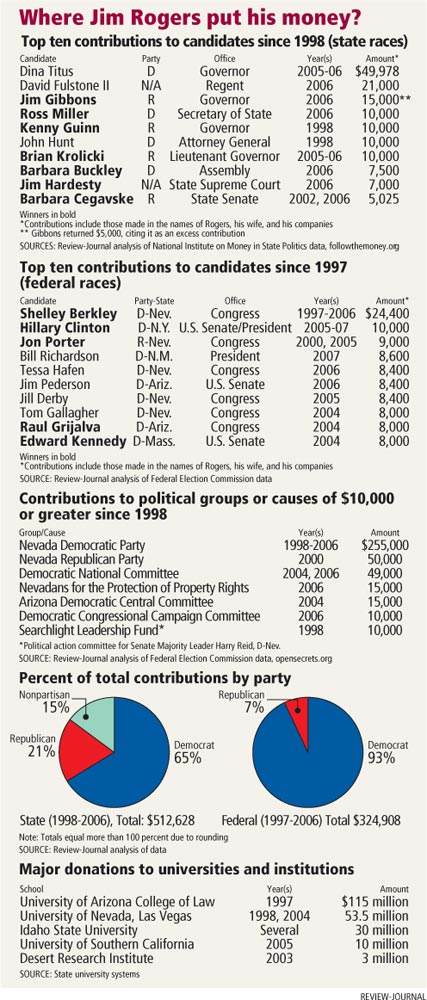

And since he became chancellor, he has ramped up financial support of candidates in state, local and federal races. Rogers and his wife, Beverly, have contributed about $1 million to campaigns over the past decade, according to a Review-Journal analysis of election finance records.

Rogers' propensity for writing checks has caused suspicion among those who say he tries to unduly influence elected regents and the university system. His charitable contributions have also won him high praise.

For his part, Rogers says he is fed up with all the talk about his wealth.

"I'm tired of getting beat up because we're rich," Rogers said in a lengthy interview earlier this month. "It's really very deflating."

But love him or loathe him, Rogers and his money are inextricably connected.

ROGERS GIVES

During a 1989 trip to Tucson, Rogers paid a visit to old haunts at the University of Arizona.

The furniture in the law school's lounge looked familiar. It turned out to be the same stuff that was there when he was a pre-law student at the university 30 years earlier.

Rogers, who in the late 1980s was a practicing lawyer and owner of several television stations in the Western United States, forked over $8,000 for new chairs and sofas.

One gift to the law school led to another. Eventually a philosophy developed.

Rogers, with encouragement from his late friend and law partner Louis Wiener, decided over a period of years to give away his entire fortune to universities, because he credited his successes in life to education.

In 1997, Rogers made a splash by pledging $115 million to the University of Arizona law school that today bears his name.

People took notice.

"Once we made that donation to the University of Arizona, people were lining up at the door," he said.

Rogers followed up that gift the next year with a $28.5 million pledge to the William S. Boyd School of Law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Today, Rogers donates his $23,660 salary, the minimum required by state law for a chancellor, back to the university system.

Former University Regent Jill Derby, who got money from Rogers for her failed congressional bid last year, said Rogers has been a boon for higher education:

"He doesn't need the chancellor job. He doesn't need to give the money he gives. He's a generous man with a big heart. ... He's always invested in good leadership."

Rogers, who says he's worth about $300 million, expresses a certain naivete about some of the other places his money has gone, including radio stations, journalism conferences and teaching programs.

"Some of the people I've given to I've never even heard of," he said.

That sentiment, real or not, extends to money he's given politicians.

"I'm not a schmoozer, not a very political animal, not a political junkie," he said. "I've never asked a politician to do anything for me. ... Everyone knows I'm a soft touch."

He's quick to mention that he gives to both candidates in some races, citing his nearly equal contributions last year to U.S. Rep. Jon Porter, R-Nev., and Porter's Democratic challenger, Tessa Hafen.

After Hafen lost the race, Rogers pegged her to lobby on behalf of the university health science system. That hiring irked some regents.

A longtime Republican, Rogers switched his registration to independent in 2005 after catching flak from both parties for where he directed his money.

"I said to hell with this; I'll give it where I want," Rogers said. "I was tired of the bitching, so I became an independent."

But campaign finance records show Rogers overwhelmingly has supported Democrats.

Rogers said his wife, whom he calls "a flaming liberal," has taken the lead in some of those decisions.

Altogether, Rogers, his wife, Sunbelt Communications and his other companies, have given $255,000 to the Nevada Democratic Party since 1998. The state Republican Party has gotten $50,000 from him, but not a dime since 2000.

Republican political consultant Sig Rogich applauds Rogers' philanthropy and support of political candidates but wishes Rogers gave more to the GOP.

"I'd like to see us get our fair share," Rogich said. "That incentivizes me to give him a call."

In all, Rogers has contributed more than $500,000 to state races and groups in the past 10 years, according to an analysis of data from followthemoney.org, a Web site of the nonpartisan National Institute on Money in State Politics.

Rogers has given to the campaigns of 43 candidates for state office since 1998: 20 Democrats, 12 Republicans, and 11 seeking nonpartisan offices such as judge and university regent.

About two-thirds of his spending on state races has gone to Democrats and affiliated groups.

Kirsten Searer, deputy executive director of the Nevada Democratic Party, said Rogers has been a key player in the party's rebuilding process.

"He has helped us at key times when we needed a bump, whether we needed to hire additional staff, get a message out, or reach out to voters," Searer said.

Another $324,000 of Rogers' money has gone in the past decade to federal candidates and organizations, according to Federal Election Commission data. More than three-quarters of that amount, or $246,700, has been doled out since Rogers became chancellor. A whopping 93 percent has gone to Democrats and Democratic causes.

U.S. Rep. Shelley Berkley, D-Nev., has been the largest individual recipient of his largesse, having received $24,400 since 1997.

In the 2005-06 election cycle, Rogers' Sunbelt Communications was the 10th largest contributor in Nevada to federal campaigns, giving a total of $136,100, according to opensecrets.org, a Web site run by the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics.

Rogers is the state co-chairman of Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign and has given $10,700 to Clinton. Before endorsing Clinton, he contributed $8,600 to New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson's campaign for the Democratic nomination.

Among current elected officials, Rogers has since 2000 given to four of seven Clark County commissioners, three of seven Clark County School Board members, and three of six members of the Las Vegas City Council, according to county campaign finance data. All of the recipients are Democrats or nonpartisan.

Rogers downplays the ideological significance of his campaign contributions.

"I only give to those who I think are honest," he said. "I'm not knowledgeable enough to know the specifics of what they're doing."

He said he's only turned down a handful of politicians who have asked him for money. That list, he said, includes former Clark County Commissioner Dario Herrera, who sought a contribution while running for Congress five years ago.

"I didn't feel comfortable with him," Rogers said of Herrera, who was convicted last year of taking bribes while on the County Commission.

Rogers' most recent federal contribution went to another politician whose integrity has been questioned.

In late June, Rogers gave $1,000 to U.S. Sen. Larry Craig, an Idaho Republican whose political career is in jeopardy after he was accused of soliciting sex in a Minneapolis airport restroom. Craig is one of only three Republican senators to have received $1,000 or more from Rogers. Twenty-three Democrats seeking Senate seats have gotten at least that much from him.

Rogers, who owns a television station in Twin Falls, Idaho, said he couldn't find any record of making a contribution to Craig but won't consider asking for his money back.

Rogers said he and Craig, who supports the storage of nuclear waste at Yucca Mountain, have met and talked about that issue.

"I told him we were trying to get it dumped somewhere else," Rogers said.

A SLIPPERY SLOPE

Nobody disputes that Jim Rogers is opinionated.

In the run-up to last year's gubernatorial election, Rogers accused Republican candidate Jim Gibbons of being "narrow-minded," "simplistic" and not "very bright."

Rogers, who had flirted with the idea of running for governor himself, eventually opted to keep his focus on higher education.

Despite the slight, Gibbons got $10,000 from Sunbelt Communications. He returned another $5,000, citing "excess contributions."

Rogers meanwhile pumped nearly $50,000 into the coffers of Democratic challenger Dina Titus by contributing under his and his wife's names and the names of his companies.

Today, Rogers is diplomatic when describing his relationship with the governor.

"We get along very well. He's been very supportive and responsive," said Rogers, who also gave $2,000 to the unsuccessful congressional campaign of Gibbons' wife, Dawn, last year.

The Gibbons camp denies any hard feelings.

"A lot of things are said during campaigns," said Melissa Subbotin, Gibbons' spokeswoman. "You don't take them to heart or take them personally."

But Ada Meloy, general counsel of the American Council on Education, said Rogers showed questionable judgment by publicly bashing Gibbons, who now plays a major role in higher education funding in the state.

"Some chancellors are undoubtedly willing to engage in public discussions, but distinctions have to be made when one's speaking in an individual capacity or as part of the university system," Meloy said. "It all sounds like the Wild West to me."

Rogers has drawn criticism for other views, including his endorsement of a state income tax.

But perhaps his biggest source of trouble involves money, namely that which Rogers has given to the campaigns of some university regents, at whose pleasure he serves.

Nevada is one of only four states in the country with elected boards of regents.

Rogers' second largest contribution to a state candidate since 1998 went to David Fulstone II, a friend and former head of the foundation board at Desert Research Institute, a nonprofit research campus of the university system.

Rogers' contributions of $21,000 accounted for 38 percent of what Fulstone raised for the campaign.

Rogers wasn't breaking any laws, but his outpouring of financial support didn't sit well with Fulstone's opponent, Ron Knecht, a former Republican assemblyman who ended up winning the race.

Since taking office, Knecht and Rogers have clashed.

In an evaluation of the chancellor earlier this year, Knecht blasted Rogers as a "self-absorbed, self-indulgent bully and tyrant."

Knecht has questioned, among other things, Rogers' power to fire university presidents and has called for stricter requirements for university system executives who give money to candidates for the Board of Regents.

Rogers has responded by calling Knecht a "vicious and malicious person" with a personal vendetta against him and his family.

Novak of the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges said Rogers went out of his way to create a problem for himself by backing Knecht's opponent.

"The unsolicited advice I'd give the chancellor going forward is don't contribute to regents' campaigns," Novak said. "It's not worth the aggravation and hassle."

Besides helping to finance Fulstone's campaign, Rogers has given a total of $12,500 to three other candidates for regent seats since 2004.

Rogers said he would continue to make such contributions, saying, "I've never tried to buy a regent. I've never asked any regent to vote on any issue in any way."

ROGERS TAKES AWAY

The Knecht-Rogers feud escalated to the point where Rogers backed away from future donations to Nevada's colleges and universities, starting with $3 million he had planned to give the University of Nevada, Reno for a classroom building.

For Rogers, Nevada's loss is someone else's gain.

"Are schools going to end up benefiting from it? Yes, it'll just benefit other schools," he said. "Even if it's unreasonable, it's our money."

For national higher education experts, it's a potential hit on the credibility of the state university system.

"If it were a regular donor who was pulling away a gift from an institution for whatever reason, it's always an embarrassment," Novak said.

Rogers insists his decision won't have negative consequences for fundraising.

"If I go out to see Joe Doe and say this is a great system that he should give to, he'll understand my sourness over this is a result of the mean and vicious attacks on me," Rogers said.

Rogers says he can be effective as chancellor in the last two years of his contract.

He said his ideas and focus on results can help a struggling university system, even if his money won't anymore.

"One of the reasons I got this job is money," Rogers said. "That's not the same as saying I'm not competent to be chancellor. ... The status quo way of handling things (in the system) has to change. I'm someone who I think can make it change."