Lake Mead eagles soaring

They stood like fire hydrants atop rocks and cliffs along Lake Mead's shoreline with their snowy white heads and brownish-black bodies silhouetted against a partially cloudy sky.

Some glided overhead with their necks craned downward and their yellow eyes focused on the lake's clear water hoping to spot a rainbow trout, a carp or even a striped bass cruising near the surface. A coot paddling through the shallows would make a fine meal as well.

When wildlife biologists look back on it, 2008 will be a banner year for the bald eagle that until last year was an endangered bird.

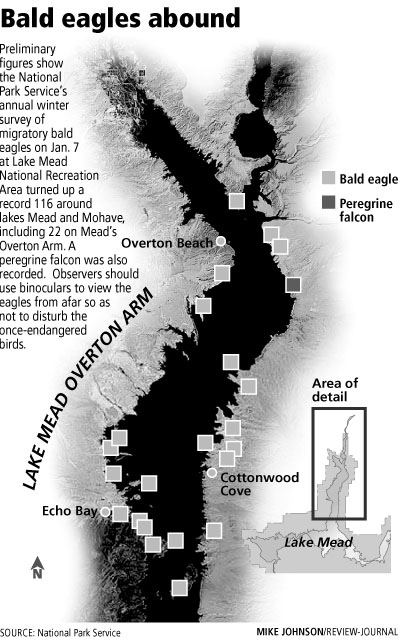

Migratory bald eagle sightings at Lake Mead National Recreation Area soared to a record high of 116 during the National Park Service's winter survey on Jan. 7, shattering the previous high of 87 from last year and giving hope that the national icon can stay off the endangered species list.

The bald eagle remains protected under other laws aimed at ensuring its survival.

The preliminary results of the survey show that the 116 total for bald eagles consisted of 94 at Lake Mead and 22 on Lake Mohave in the recreation area that straddles Southern Nevada and Arizona.

One golden eagle was recorded for Lake Mead and two for Lake Mohave. Another six "unknown" eagles were reported for Lake Mead in the preliminary analysis.

Biologists for the National Park Service are still crunching numbers as they compare them with data from past surveys going back to 1981.

At a glance, though, it appears bald eagles that migrate to hunt on the open waters of lakes Mead and Mohave when their resident lakes and rivers freeze over in the Pacific Northwest and Canada are rebounding.

There were more immature bald eagles counted this year than adults.

"We can't say anything for certain," said Dawn Fletcher, research assistant for UNLV's Public Lands Institute who participated in the survey.

"It appears that Lake Mead's population has increased over the years," Fletcher said. "However, this could be attributed to this year's climate directing their migration, influx from other wintering grounds, possible recruitment, or it could be that favorable weather conditions on the day of the survey made it easier to spot eagles."

Fletcher noted that published research on bald eagles suggests that immature bald eagles migrate farther south than adults.

On the survey route for Lake Mead's Overton Arm -- one of eight routes on the lakes combed by teams of biologists -- the dawn-to-dusk tally was 22 bald eagles and one peregrine falcon.

National Park Service Ranger David Stolts skippered the boat carrying Fletcher, wildlife biologists Ross Haley and Corey Kallstrom and volunteer Jim Reilly, who served as navigator for the survey team out of Echo Bay.

The first eagle of the day appeared in Fletcher's binoculars near the bay's entrance.

"He's taking off again. He's going to the next cove," Haley said.

Soon after the sighting, two more eagles were entered in Kallstrom's log book, including an adult perched on a boulder overlooking a cove on the west shore.

As Stolts steered the boat to get a closer look, the magnificent bird with its snowy head leaped into flight with its powerful, dark wings and white tail contrasted against the rust-colored ridge behind it.

When observing eagles on the lake's shoreline, park officials emphasize practicing what they call "appropriate viewing behavior." That means the eagles should be enjoyed from a distance with binoculars so as not to disturb them.

On this day, following two previous days of winds gusting to 45 mph, most of the eagles were perched on ridges or standing on the shoreline, ready to leap into flight should a fish or a duck come within their striking range.

And there were plenty of ducks, coots and mergansers to be had, including mallards, redheads, buffleheads, teal and pintails.

There also were Canada geese, Western grebes, Clark grebes and a loon seen in an area from Rogers Bay to Salt Cove.

One bald eagle stood tall atop an anvil-shaped rock above Ann-Margret Beach.

"Awesome," Stolts said as the bird glided off, cupping its wings before it disappeared behind the ridge.

A couple hours later on the eastern shore, Haley focused his binoculars on a peregrine falcon.

Like the bald eagle, the peregine falcon was heading toward extinction because of pesticides that poisoned them and thinned their egg shells and from environmental degradation caused by human encroachment on their habitat.

The 17th bald eagle of the day, a juvenile, was perched on a ledge beneath the top of a sandstone cliff. It seemed to be hunkered down to avoid harassment from ravens winging nearby.

Two ravens were chasing another immature bald eagle that landed atop Whale Rock, a bit annoyed but not yielding to the ravens.

The scene was reminiscent of the "Heckle and Jeckle" cartoon featuring a pair of magpies who tried to outwit their foes, at times to no avail.

With the count still shy of the 30 that were seen on the route in last year's survey, eagle No. 19 suddenly appeared, an adult flying in the late afternoon shadows of Preacher's Cove.

"And we're praying for more birds," Kallstrom said with a laugh.

At 3:55 p.m., his prayers were answered as eagle No. 20 was seen winging westward toward a distant ridge being scaled by a dozen desert bighorn sheep.

Although the Overton Arm count at 22 was eight fewer than last year's for the route, Haley, the park's wildlife biologist, said, "It's hard to say what year-to-year variations mean.

"Our intent is to have a long-term data base that can detect long-term trends rather than get excited about variations from year to year," Haley said.

"A lot of times, we think large numbers come when we have extended periods of cold to the north and not much open water that's not frozen," he said.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers @reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0308.

Click here to view slide show