LOOKING BACK AT CUBA

Cubans in the United States seemed to collectively shrug at the news that 81-year-old Fidel Castro had resigned as president of Cuba. It probably won't change much on the communist island nation, they said. Indeed, the dictator's brother, 76-year-old Raul Castro, was swiftly named his successor, effectively stifling at least temporarily the hopes of many Cuban exiles who have been waiting years, even decades, for substantial change in Cuba.

The Review-Journal spoke to three local Cuban exiles about their memories and thoughts about the future of their long-lost homeland.

• • •

A dream deferred

Otto Merida is haunted by a recurring dream.

He lands at the airport in his native Havana, and despite a nearly 50-year absence, remembers exactly how to get to his childhood home.

It's the place he remembers last seeing his father -- who is now gone -- truly happy.

"On Sundays and holidays, we'd all get together, all the family and friends," the 62-year-old Merida said over a recent lunch at the Florida Cafe Cuban Restaurant.

But when Fidel Castro took power in Cuba in 1959, Merida's father, previously a successful businessman, lost everything and the family was divided.

"My father lost that contentment, that sense of love," Merida said. "Since I left Cuba, I've never had that kind of feeling of family again."

Merida left Cuba when he was 16 years old as part of Operation Peter Pan, in which 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban children resettled as political refugees in the United States.

"Parents were afraid for their kids, so they did a desperate act," Merida said. "They sent their kids alone to a foreign country."

Merida finished high school with other Cuban exiles in Delaware, studied political science in college, bumped around the country for a couple of years and, in 1974, decided to settle in Las Vegas.

A few years later, he helped found the local Latin Chamber of Commerce to give Hispanics a stronger political and economic voice. He has served as its executive director since 1978.

Merida has never returned to Cuba, though he's always dreamed of doing so.

"My dream is to knock on the door of my old house, go inside and see where my old room was."

But he won't visit, he said, until Fidel Castro is dead and relations between the United States and Cuba have improved.

He doesn't expect either to happen anytime soon.

"Hopefully, there will be a transition to a more democratic government, one with more respect for human rights, more free enterprise," he said. "But whatever changes, it will be very gradually."

After 46 years in the United States, Merida feels much more American than he does Cuban, and he became a U.S. citizen almost 40 years ago. He has no family left in Cuba.

"Whoever remained passed away long ago," he said. "I've lived here most of my life. I love this country. I am so grateful to this country."

But as he has grown older, he thinks more and more about what was lost in Cuba.

"The revolution took everything away," he said. "My father worked hard all his life. He was the backbone of the family. He was very proud, but was never able to provide for his family in the same way or see the family together in the same way again."

Visiting the past

Liliam Lujan Hickey last year returned to Cuba for the first time in 47 years.

In some ways, she wishes she hadn't.

"The country is so destroyed," the 75-year-old Lujan Hickey said in a quavering voice while thumbing through photographs of her recent trip. "The people are so poor. There's not enough food, no toys for the kids. It was very sad, very emotional for me."

Lujan Hickey, a former member of the Nevada State Board of Education who has a Las Vegas elementary school named for her, fled Cuba in 1960 with her first husband, Enrique Lujan, and their children, after the government raided the casinos Lujan ran there.

After briefly living in Miami; York, Pa.; and San Diego, the family came to Las Vegas in 1964. Enrique Lujan died in 1972, and Liliam married Tom Hickey in 1981.

Hickey is a former state senator.

Lujan Hickey decided to return to Cuba last year at the urging of her husband, because her 80-year-old brother, who still lives there, was ill. He has since recovered.

"I was very nervous, afraid to go, because I have become more American than apple pie and Chevrolet," said Lujan Hickey, a U.S. citizen. "I didn't know what to expect."

She was caught off guard by how much things had changed.

Her childhood home had been leveled. The country looked run-down and faded, she said.

She asked her husband, who had traveled to Cuba with her, how he would describe it.

"It was like a beautifully dressed but tattered lady," Tom Hickey said. "You know there was elegance at one time, but nobody had kept it up."

Lujan Hickey said Fidel Castro's resignation won't change anything in Cuba.

When asked how she felt about the United States' decades-old embargo against Cuba, Lujan Hickey said she believes democracy should be established in the communist country before the embargo is lifted.

"They should have a democratic election first," Lujan Hickey said.

"My wife has her own opinions," Tom Hickey interjected. "If we can trade with communist China and communist Vietnam, we should be able to trade with Cuba."

Whatever happens, Lujan Hickey said, the trip home helped cement certain long-held truths for her.

"Going to Cuba was going to the past," she said. "I'm an American."

What freedom means

When asked whether he will ever return to Cuba, Waldo De Castroverde responded by reciting from memory lines of verse from his favorite poet, José Martí:

"Yo quiero, cuando me muera

Sin patria, pero sin amo

Tener en mi losa un ramo

de flores y una bandera"

I want, when I die

Without a country, but without a master

To have on my gravestone a bouquet

Of flowers and a flag

It's De Castroverde's way of explaining why he doubts he'll see his homeland again. Like many Cuban exiles, he doesn't foresee substantial change for the nation anytime in the near future.

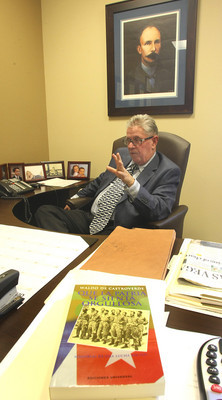

"Without a country, but without a master," the 67-year-old De Castroverde repeated, gesturing toward the portrait of Martí that hangs in his Maryland Parkway law office.

"I would love to visit, to walk the street where I grew up."

But that probably won't happen until the Castro brothers are dead, he said, and may not happen at all.

"I cannot go back, but maybe in the future. I take my (blood pressure) pills every day. If I die before he (Fidel Castro) does, I'll be very upset with St. Peter upstairs."

De Castroverde hasn't seen Cuba in nearly five decades.

At 19, after having spent most of his youth in Havana as the son of a middle-class lawyer, he volunteered to fight in the failed CIA-backed Bay of Pigs invasion, he said. He was captured and spent 20 months in a Cuban prison before being released to the United States on Christmas Eve 1962.

He landed in Miami, where he taught high school history for a while and kept up his anti-Castro activities until one day his wife, Vivian, offered him an ultimatum: either Cuba or your family.

"I decided Castro was an exercise in futility," De Castroverde said.

He ended up in Nevada, went to law school and now practices immigration and criminal law in Las Vegas.

De Castroverde has harsh words for those who see Fidel Castro as a kind of hero, a communist idol.

"In the same way that the security of roof, food and clothing that the slave masters provided to the slaves will never justify slavery, the so-called achievements of the Castro regime will never justify the suppression of individual rights," he said.

He has written a book about his life, "Que la Patria se Sienta Orgullosa," or "Let the Fatherland be Proud," and hopes that some of his four children or grandchildren will one day be able to visit a free Cuba.

The only immediate hope for that, he said, is if Raul Castro's government relaxes control enough to inspire people to want, and eventually seize, even more freedoms.

De Castroverde doesn't have much faith that the younger Cuban generation is interested enough in that kind of revolution.

"I believe Cuban youth don't care about freedom," he said. "They have never lived under freedom. They don't know what freedom is."

Contact reporter Lynnette Curtis at lcurtis @reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0285.