Middle class a state of mind

Think you are middle class?

If you are like most Americans, you do. But even if you are, you might not enjoy the comforts traditionally associated with this group: Owning a home in a decent neighborhood. Taking a yearly vacation. Putting the kids through college without mortgaging your future. Retiring before you need a walker.

Nowadays, the middle class has been largely redefined by debt, job insecurity and the struggle to maintain a lifestyle.

Against the national backdrop of a weak economy, a declining dollar and rising food and gasoline prices, more people are living paycheck to paycheck.

Many experts maintain the middle class is eroding, if not disappearing. More families are migrating to the bottom of the economic pyramid than to the top. Nevertheless, many people still cling to the idea of being middle class. And they are a varied lot.

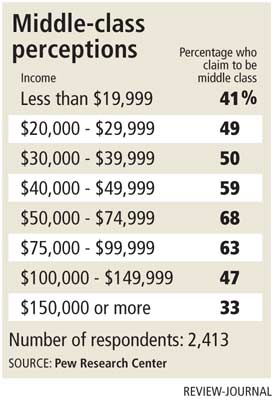

A study by the Pew Research Center shows more than half the Americans polled describe themselves as middle class, whether they earn less than $20,000 a year or more than $150,000.

Curtis Boutte, 35, counts himself among them. Before his transfer to Utah last week, he was sales manager for an Ashley Furniture Homestore in Las Vegas. His wife worked there, too. Together, they pulled in $62,000 last year. They have three children and one car, a 1994 Buick Le Sabre.

"If both parents have to work to survive, that's middle class," Boutte says. "That means the husband can't go and make it all on his own, that you need that extra income to feed your kids, make sure they have clothes on their backs."

Extras are few and far between. On the plus side, the couple has no credit card debt, and their car is paid off. Boutte says only upper-class families can afford a second car or a nanny.

But they have little savings to hedge against life's emergencies. They had to scramble to pay for a flight to Michigan after a relative died and for $100 co-payments after emergency room visits by their two sons, one of whom has asthma.

A college education, a manufacturing job and union membership all once were springboards to the middle class. They still are sometimes, but there are no guarantees.

Boutte sees evidence of this in the résumés that cross his desk.

"Before, you would not get anybody with a four-year degree even applying, and now, it's very common that you have people with college degrees applying for sales jobs and management jobs and just looking for opportunities," he says.

"Education just doesn't seem as important as it was. I think it's very important as a personal thing, but there are people out there with education that can't find work."

Politicians have acknowledged the financial squeeze on the middle class, most visibly on the campaign trail.

The Drum Major Institute for Public Policy, a progressive think tank, issues an annual scorecard showing how members of Congress vote on legislation that it says hurts or helps the middle class and those aspiring to reach it.

But for all the rhetoric, the government has no official definition of this group.

The Census Bureau breaks national income distribution into quintiles, or fifths; by the narrowest definition, the middle fifth represents the middle class.

According to a Congressional Research Service report last year, households in that quintile in 2005 had incomes spanning $36,000 to $57,660. A more generous definition of the middle class would include the middle three quintiles from $19,178 to $91,705.

"What constitutes the middle class is relative, subjective and not easily defined," the report says.

While the middle class typically refers to people within a particular income range, the label can also refer to a group that shares other traits, values or views.

In other words, being middle class can be largely a state of mind, and an American one at that.

It would appear so, judging from the recent Pew report, "Inside the Middle Class: Bad Times Hit the Good Life."

Nowhere are these differences more apparent than in the vast range of incomes reported by demographic groups, the report says. That suggests that identifying with the middle class isn't based solely on income, but on a complex mix of attitudes, behaviors and experiences.

The Pew report points out some questions that can't be answered by merely counting the digits on somebody's W-2 form: Is a $30,000-a-year resident in brain surgery lower class? Is a $100,000-a-year plumber upper-middle class?

The nonpartisan think tank admits it sidestepped such conundrums by letting people label themselves.

Fifty-three percent of the 2,413 adults Pew surveyed by phone early this year said they are middle class. Some economists say up to 80 percent of Americans claim middle-class status.

Among the rest surveyed by Pew, 19 percent each said they are either upper middle class or lower middle class. Two percent said they are upper class, and 6 percent said they are lower class.

Younger adults and older adults are more likely than middle-aged adults to describe themselves as middle class, even if they have lower incomes.

Not surprisingly, couples in which both people work are much more likely than those with only one wage-earner to say they are middle class, 61 percent versus 45 percent.

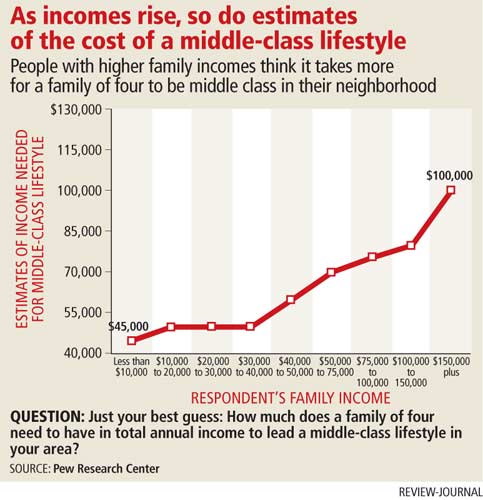

The sense of how much it takes to enter the middle class is relative to how much a person earns. Adults in families making less than $30,000 a year estimate it takes $50,000 to gain admission, whereas those earning between $100,000 and $150,000 say it's closer to $80,000.

And while many people equate the suburbs with the middle class, Pew says nearly as many city dwellers as suburban residents identified themselves with this group.

A slightly higher percentage of people in rural areas said they are in the middle class.

Half or slightly more Americans who are first-, second-, third- or even later generations said they are middle class.

Jose Beltran of Las Vegas came to this country from Mexico a little more than 20 years ago in search of the middle-class ideal: work hard and prosper.

The 45-year-old father supported his wife and three children on the approximately $63,000 he earned last year.

Beltran did it by working two full-time jobs. He's a line cook at Planet Hollywood Resort and chef at Wynn Las Vegas.

He also is studying at the Culinary Training Academy to become a certified wine server. He hopes to eventually advance to sommelier, if not master sommelier.

He's unsure how much a wine server makes, but he thinks he no longer will need a second job.

Beltran didn't finish high school. Without a diploma, he says, he would have "almost zero possibilities" for economic mobility if he didn't belong to a union. He is a member of the Culinary Local 226, Nevada's largest union with about 60,000 members.

Union membership nationwide has been declining for decades and taking some of the middle class with it. Manufacturing jobs, which have seen an accelerated drop since 2000, didn't command competitive wages and benefits until they became unionized.

Las Vegas offers what economists call "relative economic opportunity," which translates to plenty of low-paying jobs for workers with little education or few skills.

But getting and staying in the middle class can't be done on wages alone, especially low wages, says D. Taylor, the Culinary union's secretary-treasurer.

Besides decent pay, employees also need health care, a fair amount of job security, the chance to advance within the workplace and a retirement plan, he says. Culinary union members have all of those.

Taylor says he doesn't think the country will regain its lost manufacturing jobs.

"One of the things we do produce is a lot of service sector jobs that tend to be low-pay, little or no benefits, high turnover, and really, people aren't able to obtain the American dream, the middle class lifestyle," he says.

"So I think our real challenge in this country is we have to make the service sector good jobs. Because it's not like a steel plant is going to come back."

A study earlier this year by the Center for Economic and Policy Research says only one in four Americans in working families has a good job, defined as paying at least $17 an hour and offering employer-sponsored health insurance and a retirement plan or pension.

Almost one out of every five Americans in working families is "missing in the middle," the study says, meaning they live below the minimum middle-class living standard for the area in which they live.

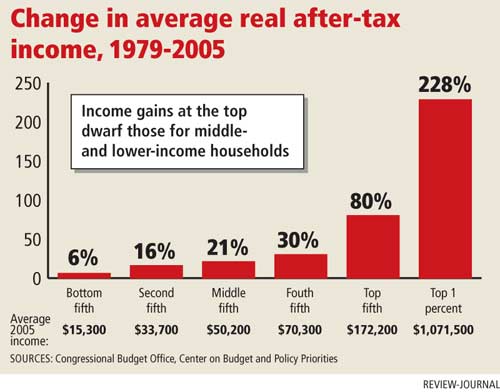

Meanwhile, the nation's growing income gap hasn't been this extreme since the start of the Great Depression.

That was the conclusion reached in December by the nonprofit Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Citing figures released that month by the Congressional Budget Office and prior research, the center noted that income among the top 1 percent of households in 2005 was more concentrated than at any time since 1929.

The Congressional Budget Office's data showed that household income inequality grew more quickly from 2003 to 2005 than during any other two-year period on record since 1979, when the CBO started gathering this information.

Real after-tax incomes jumped by an average of nearly $180,000 for the top 1 percent of households three years ago, but just $400 for middle-income households and $200 for lower-income households.

Additionally, the center said, the share of national after-tax income going to the top 1 percent of households more than doubled between 1979 and 2005. That $180,000 average income gain for the wealthiest households in 2005 was more than three times the total average income for middle-income households.

The economic divide has been under way for at least the past few decades.

As the Economic Policy Institute's Jared Bernstein told a U.S. House subcommittee in February: "Taken together, these facts (of) strong productivity growth, historically high levels of inequality and stagnant median income tell a consistent story: Working families are working harder and smarter, contributing to a growing pie, yet their slices are diminished."

The Pew report underscores that theme.

As of 2006, real median annual household income, a widely accepted measure of the middle-class standard of living, had not returned to its 1999 peak.

The majority of people Pew polled said they have either been treading water financially (25 percent) or falling behind (31 percent) in the last five years.

Over the past two decades, middle-income Americans have been spending and borrowing more, often tapping home equity that had been rising until recently. And it has become harder to sustain a middle-class lifestyle.

Naturally, how far your money goes depends on where you live.

Las Vegas, hard-hit by foreclosures, was the 36th most expensive market for home buyers among 201 cities in last year's Center for Housing Policy's study, "Paycheck to Paycheck: Wages and the Cost of Housing in America."

The Las Vegas rental market was the 53rd most expensive out of 210 cities.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Agriculture recently said the Consumer Price Index for all food is projected to increase up to 5.5 percent this year as retailers continue to pass on higher commodity and energy costs to consumers.

Beltran, the chef who is working two jobs, says economic uncertainty forced him to curb household spending for at least the past six months. His wife, Maria, also trained in a culinary academy program, and had hoped to get a job as a kitchen worker. But her prospective employer instituted a hiring freeze.

The family still attends concerts and movies and dines out, but far less frequently.

"We still go to movies, but it has to be a good movie," Beltran says. "Before, we used to go to, like, whatever movie, but now it needs to be a good movie that everybody agrees to, and then we decide to go."

Like many others, Beltran has adopted a wait-and-see attitude, hoping the economy will improve.

"The middle class, I think we are in limbo," he says.

Consumer spending is down nationwide. But is that same uncertainty causing some workers to postpone retirement?

At least one local certified financial planner says no, nor should it.

Greg Phelps, president of Red Rock Private Wealth Consulting LLC, says it would be more painful to retire in a bull market, when the values of a person's assets are inflated, and then have to adjust to a bear market.

"That's a lot more scary to me than retiring now, and knowing that I can make it in the worst of times, and knowing that over periods of time, things are going to get better."

Most of his clients, whom he describes as middle class, have investment portfolios worth $1 million to $3 million, including the value of their homes. If they really want to enjoy retirement, Phelps says, they should anticipate needing the same income they generated while working, if not more.

The focus is not on pinpointing a set rate of return, but on structuring cash flows to survive down markets.

A conservative withdrawal rate would be 4 percent or 5 percent, he says. A person living on about $50,000 a year thus would need a $1 million portfolio.

"That's comfortable, if you plan on hoping to see your portfolio grow over time, versus deplete," Phelps says.

By growth, he means in excess of inflation.

It's the prospect of inflation that concerns Irma Dutch, one of Phelps' clients.

The retired widow keenly recalls the financial struggles of an uncle and his wife during an earlier recession.

"He had all these plans for wonderful things, and inflation came and ruined them. Just ruined them."

Dutch says she feels rich. Her home in Henderson is paid for, and she can afford to do what she wants. She credits her husband, who died in 1992, for making wise investments that allow her to live on about $50,000 a year.

Her lifestyle isn't lavish, but she enjoys some perks.

A chef brings her many prepared dinners each month. She has a housekeeper and a personal assistant who organizes her bills and research on subjects of personal interest.

But she will have to let them all go if the cost of living rises too high, she says.

Boutte, the Ashley Furniture sales manager, recently transferred to the company's new store outside Salt Lake City. His income will stay in the same range, but he expects his spending power to increase because the area has a much lower cost of living than Las Vegas.

Who knows, he says. Maybe his wife, Brandy, won't have to work anymore.

"It's a dream," Boutte says.

The squeeze of the middle class has been well documented by academia and think tanks, almost mimicking a rush of anthropologists to record the social and behavioral characteristics of a group before it becomes extinct.

UNLV sociology professor Robert Parker has been studying social inequality for years.

He says life is more stressful nowadays, partly because more people recognize that employer loyalty, and thus job security, is a thing of the past.

"Part of being middle class today, qualitatively, is a harried lifestyle, the breakdown between work and leisure. I don't see anyone in the middle class who turns off their (electronic) stuff when they come home at night because there is still work to do," he says.

Parker sums up how the middle class has been redefined since the 1950s: "We've traded permanent pensions for permanent work."

Contact Margaret Ann Miille at mmiille @reviewjournal.comor 702-383-0401.