MIXED BLESSING

The streets in historic West Las Vegas are usually mostly empty, except for one day of the week: Sunday.

That's when thousands of people from across the valley flock to what once was the bustling center of Las Vegas' black community to attend church, and they have plenty of options.

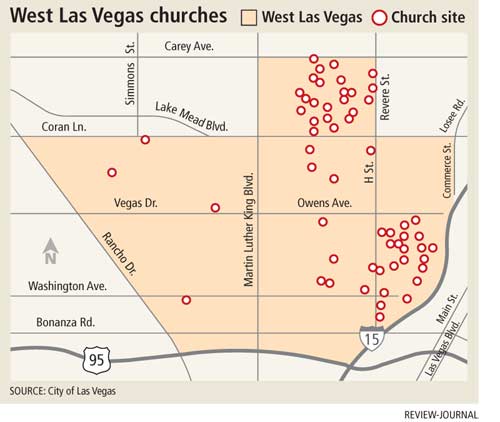

A city survey recorded 46 religious facilities in the area bounded by Rancho Drive, Lake Mead Boulevard, Interstate 15 and U.S. Highway 95, most of them packed into the area east of Martin Luther King Drive. Religious uses take up 2.9 percent of the land area in the district, compared to 0.6 percent citywide.

And while the churches (and a mosque) have been stable anchors in an area known for old buildings, vacant storefronts and empty lots, the concentration in this area could severely limit what kinds of businesses could come into an area in desperate need of residents and investment.

"It hinders the opportunity for development," said Las Vegas Councilman Ricki Barlow, "whether it be residential or, most notably, commercial and retail. We must come up with a plan to marry the two and see how we can work with the existing ones, but also be smart about where future churches come online."

Certain kinds of businesses aren't supposed to be close to churches and associated uses, such as a church-run day care. In West Las Vegas, those limits effectively bar businesses selling alcohol from large swaths of the area.

That's particularly true on Jackson Avenue, which once was known as the "Black Strip" because of the casinos and nightclubs that had sprung up starting in the 1940s, when blacks couldn't frequent the casinos on Las Vegas Boulevard.

"If a 7-Eleven wanted to set up on Jackson Street, they would not be able to apply for a liquor license, or a beer and wine license," Barlow said. "They would not be able to meet the distance separation because of the religious facilities.

"Throughout the city, you have all types of uses, not one particular use. It needs to be a mixture."

Pastor Robert Fowler at the Victory Missionary Baptist Church understands that, but he'd rather not see some uses, including alcohol sales.

"I would object to that for theological reasons and sociological reasons," Fowler said. "I think there's enough liquor in this city. But I understand people have to do business."

His church lists 14,000 members, about half of whom visit the church in any given week.

The church owns about three acres around the 500 blocks of Monroe and Jackson avenues. While a lot of that is reserved for parking, there are big plans for some of the property, including a health clinic, a Christian theater, a school for boys and job training programs.

Some of that might not mesh with redevelopment ideas, which include bringing in various kinds of housing, multi-use buildings with street-level retail and even re-establishing Jackson Avenue as an entertainment district.

"I do envision some conflict, but I also envision some opportunity," Fowler said. "This presents a tremendous opportunity for us to show how communities can come together."

Next door, at the Second Baptist Church, which owns about three acres around Madison Avenue and E Street, the Rev. Namon Johnson said he's not as concerned about what kind of businesses come in, just that they come.

"There's space for all of us. It's a benefit for the community, no matter what it is."

Redevelopment will only benefit the community, though, if it creates housing and job opportunities for the people who are already there.

"Right now if you drive through here, there's nothing to employ anybody," Johnson said.

Barlow said he has planned a town hall meeting and a meeting with area pastors. He acknowledged that some of the economic development plans might run smack into religious objections.

"I don't have the answer to that," he said. "There are a lot of 'what ifs' we're going to run across."

Contact reporter Alan Choate at achoate @reviewjournal.com or 702-229-6435.