Burns Paiute Tribal Council calls on armed protesters to leave Oregon standoff site — PHOTOS

BURNS, Ore. — Ammon Bundy says he's ventured into Harney County to help the region get lands back from the federal government and thrive. So do the members of his band of anti-government protesters and armed self-styled militiamen, who are occupying a national wildlife refuge in southeastern Oregon.

But as the occupation enters its fifth day, calls are growing for Bundy and his group to peacefully leave the headquarters of Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, which is about 32 miles south of Burns, a small city of about 2,800 people. The Burns Paiute Tribal Council on Wednesday called on the group to leave the refuge, saying its presence desecrates the tribe's ancestral land and endangers the community.

Harney County Sheriff David Ward has already asked the group to leave the region. Ward had a community meeting Wednesday to address safety concerns that drew more than 500 people and packed a fairgrounds building. His comments, and those of many others, made it clear that the locals view the protesters as outsiders.

"You don't get to come here from elsewhere to tell us how we're going to live our lives," Ward said, drawing thunderous applause from meeting attendees.

Bundy's group is staying within a complex of about a dozen buildings, insisting that federally owned land, in Harney County and across the West, must be turned over to counties and the states to manage for the benefit of ranchers, farmers and sportsmen.

Bundy, speaking to reporters on Wednesday, said: "There is a time to go home. We recognize that. We don't feel it's quite time yet."

Ward wants the group to leave the refuge and avoid violence.

"At this point, nobody's been hurt," Ward said.

The nearly two-hour meeting included a range of public comments from the locals. Some volunteered to go with Ward to tell the group that it needs to leave. Others who have been out to the refuge and visited with the protesters said the protesters are approachable and are keeping the property clean.

Georgia Marshall, a fifth-generation rancher in Harney County, said relationships with the Bureau of Land Management have improved and it's important to not let the standoff define the county.

"It's our moment right now," she said. "We don't know our future, but I'll tell you what, it's better than what we had, so let's try to keep going."

She added, "My boots are shaking, but I'm proud of who I am. I'm proud to be a rancher and I'm not going to let some other people be my face."

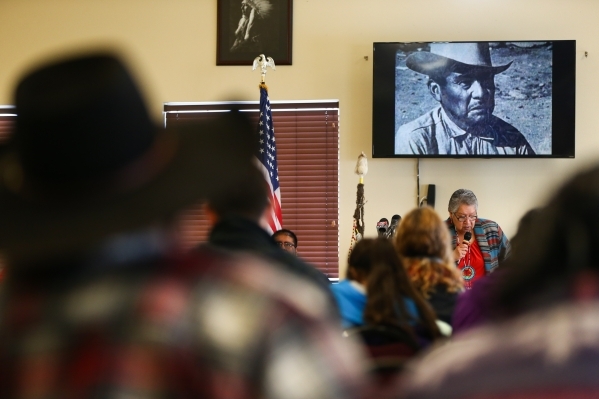

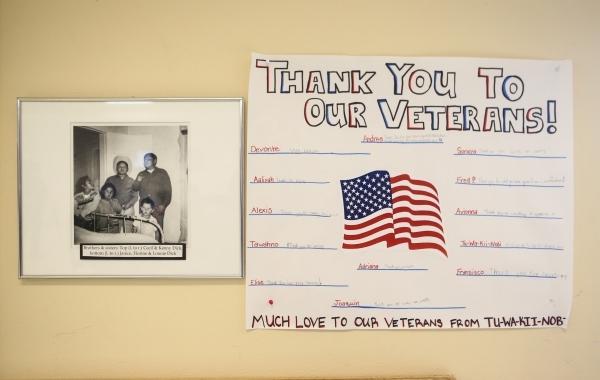

TRIBE CAME BEFORE RANCHERS

The tribal leaders, whose ancestors once wintered on the refuge's lands well before the first pioneer crossed Oregon, don't want the group there.

"Armed protesters don't belong here," Charlotte Rodrique, the Burns Paiute Tribe's chairwoman, told reporters Wednesday. "By their actions they are desecrating one of our sacred traditional cultural properties. They are endangering our children, and the safety of our community, and they need to leave. Armed confrontation is not the answer."

The tribe's ancestral territories include the refuge and encompass southeastern Oregon and into parts of Idaho and California and northwestern Nevada, extending south of Carson City. The tribe never officially ceded its rights to the ancestral territory.

The tribe, which has 420 members, has a reservation on almost 1,000 acres north of Burns where about half its members live.

Rodrique drew laughter when she joked about the protesters' claim that they're giving land back to its rightful owners.

"I'm sitting here trying to write an acceptance letter when they return all this land to us," she said.

When Ammon Bundy, in a Wednesday press conference, was asked about the tribe's comments, said he wasn't familiar with the tribal territory issue.

"I really don't much about that so that is interesting and they have rights as well," he said. "I would like to see them be freed from the federal government as well. They're controlled and regulated by the government very tightly, and I think they have a right to be free like everybody else," Bundy said.

Rodrique said she doesn't feel oppressed.

"I think oppression is in their minds," she said. "It's not in our minds."

STANDOFF ORIGINS

The occupation started Saturday after a peaceful march in Burns in support of Oregon ranchers Dwight Hammond Jr. and his son Steven Hammond.

A jury convicted the Hammonds in 2012 of starting fires on public lands, burning about 140 acres. Federal prosecutors said the fires were set to cover up poaching. The Hammonds, who turned themselves in Monday to start five-year federal prison sentences, said the fires were set to protect their property from invasive plants and wildfires. The Hammonds' attorney has said the protesters don't speak for his clients.

Bundy has said the group is gathering evidence in an effort to exonerate the Hammonds, saying witnesses saw federal agents ignite fires. Bundy didn't identify the witnesses.

Bundy's father, Bunkerville rancher Cliven Bundy, was involved in an armed standoff in Southern Nevada between his supporters and federal agents in April 2014. The agents had rounded up Bundy's cattle after he didn't pay grazing fees for using public lands. The agents released the cattle and no shots were fired.

Contact Ben Botkin at bbotkin@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2904. Find him on Twitter: @BenBotkin1