Panic or pandemic, angst is natural

Now that things seem to be dying down, so to speak, it is time to ask the question we'd all like to pretend doesn't need asking: What the hell happened to us?

Did we really empty the shelves of medical masks?

Did we really fill the pantry with Clorox wipes and Purell and beg our doctors for Tamiflu and skip the breakfast sausage and take a just-in-case detour around the pig farm because of this?

Yes. Yes we did.

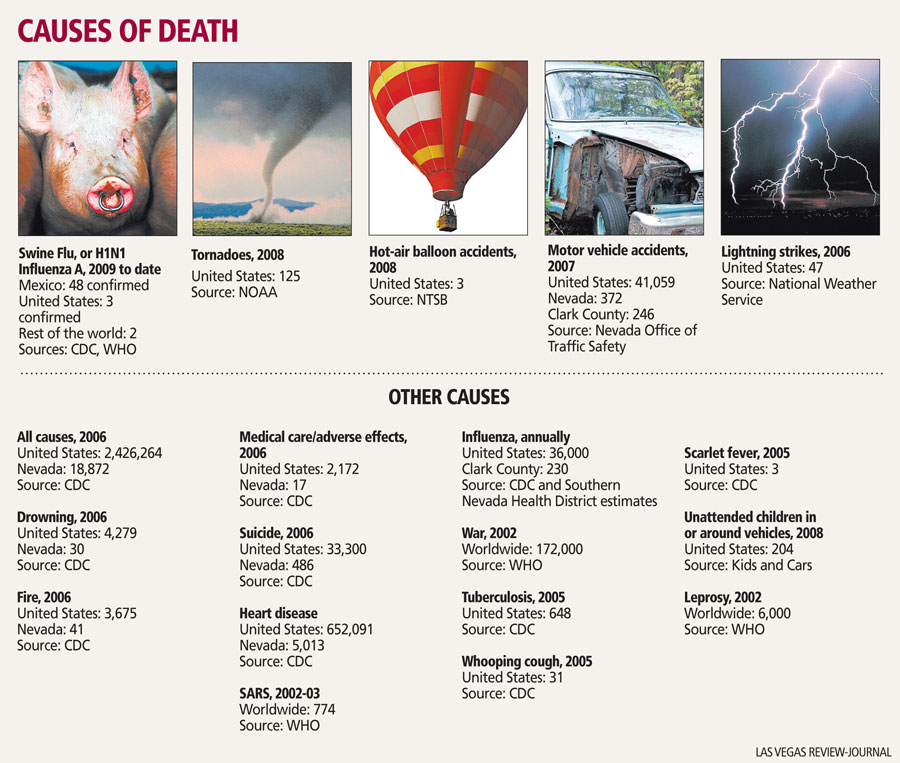

An average of 100 people die every day in the United States from the flu -- the regular old flu.

The one that slams into you like a truck every few years and makes you feel older than you really are.

This flu?

This flu with the funny name that has crowded other stories off the front page and that has forced the Cable-bots to forget their true mission, taking advantage of the unfounded child abduction fears of the parents of pretty children?

Three.

It's been a factor in three deaths in the United States.

A little boy, who came here from Mexico, a Texas woman, and a Washington state man.

All three had underlying medical conditions.

As many people died nationally in hot-air balloon accidents last year.

"Hiding and going into mass hysteria is going to make things worse," said Dr. Daliah Wachs, a local family practitioner who hosts a call-in radio show. "It's ridiculous."

That's not to say it isn't also serious. That it might have been a whole lot worse. That it couldn't get worse. That some day we might look back at The Great Swine Flu Spike of Spring '09 with nostalgia as a simpler, less scary time.

Epidemiologists, after all, don't hold news conferences just because they can.

"It looked like, initially, we had a possibility of a really bad virus," said Dr. John Middaugh, community health director for the Southern Nevada Health District. "Exactly the nightmare the whole world has been trying to protect itself against."

Turns out, this H1N1, this swine flu, doesn't seem so bad. But we didn't know that then.

What we did know was this: The flu mutates all the time. It makes copies of itself. It messes up some of those copies.

Most of the copies are blurry and harmless. A few are bad. A very rare portion are pandemic material. The kind that can sweep the world.

A mutated strain of the H1N1 flu did that in 1918. That flu infected the entire planet. It killed 50 million people, which is nearly as many as World War II took.

It could happen again. Some say it probably will.

Five years ago, a strain of the bird flu mutated. It struck Asia. It killed several dozen people, but was incredibly potent.

As many as two-thirds of the people who got it died. It could happen again.

So, what to do about it?

We monitor. When a new flu strain comes up, the health authorities watch what it does. If it seems deadly, they react.

Which is what happened here.

The reports coming out of Mexico, at first, made it seem like this flu had a fatality rate of 10 percent or more. Many dozens of deaths were attributed to it. Hundreds or thousands were predicted.

So there was an abundance of caution. Recommendations for school closures. Talk of border closings. These are the things that will happen if a truly deadly pandemic ever does strike.

And then the public reacted. Some people went crazy.

"We just had an onslaught of companies calling us," said Steve Skelton, area manager for Zee Medical, which sells basic medical supplies to cubicle farms all over the valley.

He said the big sellers were masks and hand sanitizers.

"Pretty much everything we had in antibacterials," he said. "Just gone. Everything. Within, like, three days."

Wachs, the family doctor, said she heard stories of Tamiflu hoarding. Patients wanted it, even if they didn't need it. Emergency rooms bustled with potential patients, coughing and sniffling. Diagnostic labs were in disarray.

The Internet also went crazy. Google "aporkalypse," for example, or "hamageddon," "hamdemic," "epigdemic," "snoutbreak" or any variety of clever puns.

Lots of people, apparently, think the swine flu is hilarious.

Dan Ariely, a professor of behavioral economics at Duke University, studies why people do the things they do. He's the author of "Predictably Irrational," a book that explores the seemingly senseless decisions we make.

He said there are a couple of reasons nobody's scared of car wrecks -- they killed an average of one person every day last year in Nevada -- but lots of people are scared of the swine flu.

First, fear of the flu is not completely without reason.

Second, people fear the unknown; in this, the swine flu is a lot like terrorism, Ariely said. You never know when or where it's going to hit. Joking about it can make it seem even less real.

"But a car accident? You feel that you have control," Ariely said. You don't, of course, but you feel like you do.

And third, people like stories. The swine flu is, indeed, a compelling story.

Or it was, anyway.

The deaths in Mexico aren't rapidly approaching the hundreds, as they were said to be in the beginning. They're at 48 so far.

This flu strain doesn't appear to be worse than the regular flu. While that's bad, it's probably not a worldwide threat.

So the recommendation to close schools was lifted. The headlines are smaller now, and the authorities are looking ahead. They're trying to decide whether this flu will come back in the winter. They're trying to decide whether to incorporate it into the next season's vaccine. In short, they're trying to decide if it will be more dangerous if it has a second incarnation.

"We expect this thing to disappear or smolder throughout the summer," said Middaugh, the local epidemiologist. "Next fall, it could re-emerge."

Which will bring the fear, again, and the jokes, again, and the criticism of those jokes and that fear -- again.

Middaugh, however, noted that the overreactors, the jokesters and the critics probably do not represent most people.

Most people will wash their hands a little more often now, he said. They'll cover their mouths when they cough. They'll stay at home when they're sick, just like the health authorities recommend.

He pointed out what's always been true. We -- the public, the media -- tend to notice extremes, the crazies on both ends. We don't see the middle, the huddling mass of people who are just like us, who are going about their lives with a small bit of worry, but no panic.

We keep an eye on things, we hug our kids tight, we change our behavior when it's necessary, we hope for the best.

And then we move on.

Contact reporter Richard Lake at rlake @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0307.