Pay for government workers in Nevada are straining budgets

At a legislative hearing last month, the leader of a government-employee union declared that the Democrats' crushing victory in November was a mandate for organized labor.

Since the election, however, the stock market has plummeted, Nevada's foreclosure and unemployment rates have skyrocketed to some of the highest in the country and state lawmakers -- who scoffed at Republican Gov. Jim Gibbons' budget cuts in January as severe, short-sighted and unnecessary -- are faced with a deficit that grew to about $900 million based on figures released May 1.

So, six months after the Election Night celebration, the tangible fruits of victories past -- salaries, pensions and health coverage that are considered some of the most generous in the nation -- are at risk of reduction.

Government-employee unions helped Democrats lock up all seven seats on the Clark County Commission, increase their majority in the Assembly and take control of the state Senate. Yet the Legislature is looking at the first reductions in 18 years to salaries for state workers and teachers, and cuts to the health insurance and pension benefits enjoyed by employees of Clark County, the Clark County School District, Southern Nevada cities and other public agencies up and down the state.

"We are going to see reform, because it is going to be very difficult for the legislators to sell tax increases without first showing that they are trying to get a handle on the expenses," said Carole Vilardo, president of the Nevada Taxpayers Association. "It is going to be very difficult -- given this economy -- to ask for tax increases if, in fact, you haven't tried to rein in some of the expenses that, in effect, take money away from the programs you need."

Nevada has one of the lowest ratios in the nation of state and local government employees to residents they serve. On the other hand, Nevada pays some of the highest local government salaries in the nation; and local governments in Nevada contribute the nation's highest percentage by far toward employee pension plans while the employees' own contributions are among the lowest.

Personal income in Southern Nevada has not kept pace with the growth in total revenue per capita collected by government agencies, nor with the growth in government salaries.

"There is a growing gap between the salaries and benefits of governmental workers and the private sector," said Steve Hill, chairman of the board of directors at the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, which is lobbying state lawmakers to reduce government salaries and benefits. "We have to bring some balance back between what state and local government workers are paid and what the private sector gets paid. ... The gap is growing, and the people paying for these (government) jobs don't think that is fair."

State Senate Majority Leader Steven Horsford, D-North Las Vegas, and Assembly Assistant Floor Leader Marcus Conklin, D-Las Vegas, the lower house Democrats' expert on government employee salaries and benefits, did not return repeated phone calls.

Also, Dennis Mallory, chief of staff for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Local 4041, in Carson City, which represents many state workers, did not return repeated calls.

Al Martinez, president of the Service Employees International Union, Nevada, which represents Clark County employees, could not be reached for comment.

Lynn Warne, president of the Nevada State Educators Association, which represents nearly 28,000 teachers and other employees, said Gibbons' proposal to cut the salaries of state workers and teachers is unfair, and that he should be looking at sharing the burden among "other employee groups." She declined to name such groups.

The state is last in the nation in per pupil spending, and already has difficulty attracting and retaining enough qualified teachers to fill classrooms at the start of each school year, Warne said, adding that cutting teacher salaries and benefits will make it even more difficult.

Gibbons "is trying to balance the budget on the backs of teachers and state employees," Warne said.

State officials don't control the wages and benefits of local and county workers, but Gibbons has proposed taking $64 million in property tax revenue from Clark County and $12 million in property taxes from Washoe County to help address the state's deficit.

Democratic lawmakers, who three months ago criticized the tax-shift proposal, have warmed to the idea in the face of the escalating deficit. The Democrat-controlled Assembly Ways and Means Committee is scheduled Monday to hold a hearing on the tax shift.

Government jobs represent about 13.5 percent of all employment in Nevada, but they represent only 1.5 percent of the jobs lost from March 2008 to March 2009, said Jeremy Aguero, a principal with Las Vegas-based Applied Analysis. His firm was hired by the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce to study personnel costs.

While tens of thousands of Nevadans have been laid off, unions for workers with Clark County, the city of Las Vegas, the Las Vegas police and other local government agencies in the past couple of months have agreed to shave cost-of-living raises this year that, over the past 10 years or so, have averaged nearly 7 percent a year when coupled with regular "merit" raises.

"That means you have (tens of thousands of) former, private sector workers that are contributing less to the tax base. Meanwhile, the number of government workers that benefit from that tax base is essentially unchanged," Aguero said.

GOVERNMENT EFFICIENCY

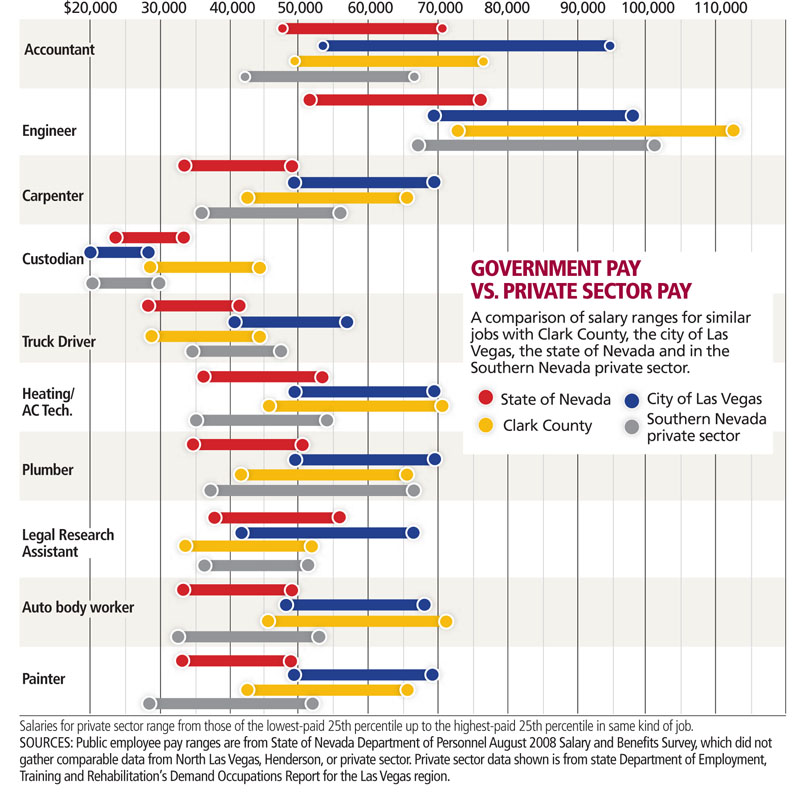

Bruce James, chairman of Gibbons' budget advisory committee, the Spending And Government Efficiency Committee, or SAGE, said the bipartisan group's research found that state workers do not receive much more in salaries than workers in comparable private sector positions, but that county and city workers make far more than their counterparts in state or private sector jobs.

State and local government workers also enjoy better health insurance, pension and other benefits than private sector workers, he said.

Aguero said his research shows that Clark County and city workers in Southern Nevada make an average of 28 percent more than their counterparts on the state payroll.

Unlike state workers, who are not entitled to collective bargaining for higher wages and benefits, unions for government employees in Southern Nevada have successfully negotiated generous contracts during the past decade. For instance, the four-year contract approved in 2006 with Las Vegas police officers assured most officers a pay raise of nearly 10 percent a year.

Republicans this legislative session do not have a proposal to change the laws affecting collective bargaining, and attempts to alter it have been derailed by Assembly Democrats.

However, Assembly Minority Whip Pete Goicoechea, R-Eureka, a member of the lower house's powerful Ways and Means Committee, said he is supporting an amended version of a Democratic proposal aimed at extending collective bargaining to state workers. The amended version, which passed the Assembly May 1, allows state workers to bargain, but on matters other than salaries, he said.

"I support collective bargaining for state workers but, with the budget constraints, we can't extend it to salaries this year," said Goicoechea, who characterized the proposal as "the first step" toward establishing collective bargaining for state workers.

Although Nevada's government salaries and benefits are higher overall than in most states, ratings differ dramatically position by position. For instance, teachers in Nevada earn less than teachers in other states, but firefighters here are some of the best paid in the nation, Aguero noted.

Salaries for teachers, police officers and others are not the same in Clark County as they are in other parts of the state. For instance, Goicoechea said, a qualified teacher can make $100,000 a year in Eureka because the schools must pay more to attract them to the rural setting. However, police officers in Eureka make far less than police officers in Southern Nevada, he said.

Nevada tax revenue spent on government personnel grows every year, but the percentage of the budget pie devoted to personnel costs is in "about the middle" year after year when compared with other states, Aguero said.

The high salaries are offset by the fact that Nevada's ratio of government workers to residents is one of the lowest in the country, meaning there are few highly paid workers for the number of residents they serve.

"We have fewer employees than other states, but they are among the highest paid," Goicoechea said. "It begs the question: Are we getting more efficient or less efficient in our provision of resources?"

According to the Pew Center on the States, in conjunction with Governing Magazine, Nevada's state government scored below average among the 50 states in a study aimed at assessing management of state government. Nine states scored the same C+ grade that Nevada received, and nine states received a lower grade, according to the Pew Center's report, "Grading the States 2008."

We don't always know what we get for our money.

"The central personnel office lacks performance appraisal data," states the report on just Nevada's state government. "New employees are supposed to receive reviews at four, seven and 11 months and annually thereafter, but many managers fail to complete the necessary reviews."

RETIREMENT AND BENEFITS

Republicans say the state's Public Employee Retirement System and the Public Employee Benefits Program pose enormous liabilities that will balloon at an ever faster rate and consume an ever greater share of taxpayer revenue that otherwise could go to schools, hospitals, parks, jails, social services and road construction.

And, they insist that lowering those costs is necessary for the long-term fiscal health of the state, while some union leaders say the Chamber of Commerce and others are exploiting the sour economy to advance their longtime political agenda.

However, Democratic leaders in the Legislature, who have been shy to reveal details of any budget they may propose as an alternative to Gibbons' "no tax hike" approach, also haven't said much about the governor's proposals to reduce the fiscal burden of benefits.

The Senate Finance Committee hasn't held a public hearing on the pension reform proposal since its first meeting on the subject April 3.

If the proposal to reduce the cost of the Public Employees Benefits Program is enacted as written, it could save the cash-starved state $160 million in the next two years, said Josh Hicks, Gibbons' chief of staff.

"From the administration's perspective, PERS and PEBP reform are critical," Hicks said. "If there ever was time for fiscal reform, the time is now. If the Legislature decides to put off PEBP reform, that will create a $160 million hole in the budget that the Legislature will have to decide how to fill."

The benefit program involves primarily health coverage. Since its inception 46 years ago, eligibility for the program has expanded from just active and retired state workers to include all government employees and retirees in the state.

From 2004 to 2008, the number of state government retirees in the program jumped 27 percent, from 5,804 to 7,361, while the number of nonstate retirees jumped 246 percent, from 2,258 to 7,819.

Senate Bill 367 is sponsored by Gibbons and reflects recommendations from the governor's SAGE Commission to the state-run pension plan for state, county and local government workers.

SAGE unanimously recommended that the retirement age for most government workers be raised to 60, and 35 years of service be required to qualify for early retirement with a lower pension; that pensions be calculated from base pay only; that the calculation formula itself be changed to reduce costs; and that the new provisions apply only to employees hired after January 2010.

The proposal comes 24 years after the Legislature last took steps to reduce retirement benefits for government employees, and 22 years after the federal government dropped for new employees its traditional pension program for one more like private sector retirement plans.

Retired police officers and firefighters from Nevada in 2007 received an average of $3,549 a month from PERS, or 60 percent more than the average $2,216 received by other government employees, according to PERS data.

The average monthly pension for police and firefighters climbed 59 percent from 1998 to 2007, and the average pension for other government workers grew 51 percent in that time, according to PERS.

The average retirement age for a government worker in Nevada is 60 years with 18.5 years of service. For police and firefighters, the average retirement age is 55 after 22 years on the job, according to PERS.

"Reforming PERS and PEBP are hills to die for. We have to make changes. We can't put it off any longer," Assembly Minority Leader Heidi Gansert, R-Reno, said. "We have to take this opportunity to reform these areas now. These are very high priorities. I think there will be changes (this session). The question is how significant the reforms will be. ... They have to have a fiscal impact. We can't do a small change that gets us nowhere."

Contact reporter Frank Geary at fgeary @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0277.