Police sergeant examines veiled cop killer: suicide

After 23 years as a Las Vegas police officer, Sgt. Clarke Paris knows the perils of law enforcement transcend traditional on-the-job risks: Some cops also pose a danger to themselves.

They're in a high-stress job, after all, where they deal with a lot of tragedy.

Some officers wind up using alcohol. Before they know it, they're drinking too much, too often. Officers have high divorce rates. Some have money problems and gambling addictions.

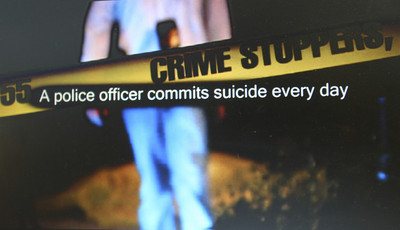

When it starts to feel like too much, some cops consider suicide as a way out, and they almost always have a gun within reach.

To try to raise public awareness about that worst-case scenario and the issues police face that lead up to it, Paris started work about six months ago on a documentary about police suicides.

He's on a shoestring $75,000 budget but has high hopes for the documentary, "The Pain Behind the Badge."

The documentary is to feature interviews with officers from departments across the country as well as experts, psychologists and spouses of officers. Paris has joined with a local production company, but he remains the creative force, conducting all the interviews himself.

His main goal is to tell officers and others that it's OK to talk about despair and suicide.

"I just want police to see it and think, 'I thought I was the only one messed up, but there are thousands who feel like this,'" he said.

Paris himself is no stranger to despair.

In 2000, he was struck by a drunken driver while on patrol on a motorcycle. He was laid up for almost six months, and doctors had to remove part of his hip to use in the reconstruction of his back. Paris was left with two steel rods, eight screws and a metal plate in his back.

While he was struggling with his injuries, he also was going through a rough divorce, his father was diagnosed with Alzheimer's and his 48-year-old brother died of cancer.

Despite that, Paris said, he never felt suicidal.

"I've never felt so down it (suicide) was my only out," he said.

Experts say one of the biggest hurdles in dealing with police suicides is getting officers to admit that they think about killing themselves.

No one likes to talk about suicide, but it's even harder for police, who must project an image of toughness and authority and don't want that tarnished by admitting that they are hurting inside, said Robert Douglas, executive director of the National Police Suicide Foundation and a retired officer who served for 25 years with the Baltimore City Police Department in Maryland.

"Officers are usually the ones who are in control, not the ones seeking advice or help," he said.

As a result, "Our biggest enemy is not the crooks on the street. Our biggest enemy is ourselves."

Police officers are eight times more likely to kill themselves than they are to be slain by someone else, according to the Metropolitan Police Department's Police Employment Assistance Program, or PEAP.

Police across the country commit suicide at a rate of about 18 per 100,000, said Audrey Honig, the chief psychologist for the Los Angeles County sheriff's office. The general population commits suicides at a rate of about 11 per 100,000.

The statistics are problematic, however, because reporting suicides varies from department to department, Honig said. Some police agencies count all staff suicides, including dispatchers and corrections officers. Others look at patrol officers only. Some count retired police officers.

Police suicides were most recently in the national media spotlight in 2005. Two New Orleans police officers fatally shot themselves in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana. Patrol officer Lawrence Celestine, and a police spokesman, Sgt. Paul Accardo, used their own guns to kill themselves.

A few years earlier, a series of police suicides in Norwood, a small city 14 miles southwest of Boston, drew some national attention. Six police officers killed themselves in Norwood over a span beginning in 1977 and ending in 2001. The only similarities in the suicides is that they all involved police officers from the same area.

Las Vegas police do not keep statistics on officer suicides, said Sgt. Tom Harmon, head of the department's Police Employment Assistance Program, which offers counseling and assistance to officers who are going through a crisis or just need to talk to someone.

Started in September 1984 by detective Ed Jensen and then-Lt. Jerry Keller (who was later elected to lead the Metropolitan Police Department as sheriff), the program is made up of six "peer counselors," a mix of officers and civilians who are trained in grief counseling, crisis intervention and basic counseling skills, said Harmon, who has been with the program for 13 years.

The program's counselors are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any officer to call and talk with. They also respond to all officer-involved shootings. The counselors can refer officers to psychologists, chaplains or other professionals.

As for how often the program is used, little public information was available. To try to ensure confidentiality, the office doesn't keep records of referral requests, Harmon said.

Paris hopes his documentary will inform the public at least in a broad sense about the issues. He expects to finish the project by the spring, then shop it around to the Discovery and Arts and Entertainment cable channels and film festivals such as CineVegas.

It might be a long shot, but Paris has had a few long shots come through in the past. In 1995, Paris founded Cops Racing Against Violence through Education (C.R.A.V.E), a nonprofit that awards scholarships to high school students who work in the community and educates students about the dangers of gang-related violence and substance abuse.

Paris also is an avid motorcyclist who competed in professional stock motorcycle racing and was ranked 12th in the nation in 1998. He was later featured in a story on the sports network ESPN2.

And in 2002 he self-published "How to Get Out of a Traffic Ticket: Best Excuses," a collection of his favorite reasons people gave for speeding.

He knows that making the documentary a commercial success will be an uphill battle. But the message it conveys is important enough for him to keep on trying.

"Cops are made of flesh and blood just like everyone else," Paris said.

Contact reporter David Kihara at dkihara@ reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-4638.