What’s the water worth?

In the parched Nevada desert, the value of water can rarely be reduced to a simple economic formula.

The cost of a water project divided by its yield will tell you only part of the story.

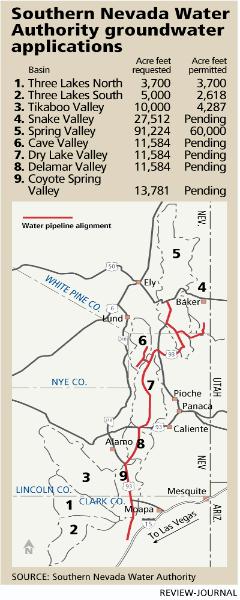

Consider the proposed pipeline to Las Vegas from six groundwater basins across Eastern Nevada.

Critics insist there isn't enough water available in rural Clark, Lincoln and White Pine counties to justify spending at least $2 billion on the project. Backers argue that Southern Nevada can't afford not to build the pipeline, regardless of the cost.

The debate gained momentum last month, after the state's chief water regulator cleared the Southern Nevada Water Authority to eventually export as much as 60,000 acre-feet of water a year from a White Pine County valley 250 miles north of Las Vegas. An acre-foot is about 326,000 gallons, which is almost enough water to supply two average Las Vegas homes for one year.

Pipeline opponent Bob Fulkerson said the ruling "throws the project into doubt" because the authority was guaranteed access to only 40,000 acre-feet, roughly half of the water it was after in Spring Valley.

"I'd be interested in knowing what they're smoking if they think 40,000 acre-feet is enough to justify a multi-billion-dollar pipeline," said Fulkerson, who is executive director of the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada. "It really calls into question their credibility."

Authority officials had the opposite reaction to the ruling, declaring the water they got more than enough to move forward.

"We have a project. It's viable," Deputy General Manager Dick Wimmer said. "I wonder if we can afford not to do it. That's the question. I don't believe we can afford not to."

Wimmer isn't alone.

Jeremy Aguero is principal analyst for the Las Vegas-based financial consulting firm Applied Analysis. In 2004, he helped author a study, commissioned by the water authority, that warned of economic catastrophe should Southern Nevada try to solve its water problems by restricting growth.

Aguero said the cost of the pipeline should be weighed against what could happen if it isn't built.

"The value of that water is more than just the ability to sell it. It's the ability to maintain jobs and a healthy economy," he said.

That becomes especially important when you consider how much Southern Nevada contributes to the state's economy. "As goes Clark County, so goes the state of Nevada in a lot of ways," he said.

Fulkerson dismisses that as typical pro-growth rhetoric.

"Their reckoning is that if one drop comes down that pipeline to enable us to build one more house, it's worth it to them. That's an exaggeration, but it's basically their thinking," he said.

The folks living at the northern end of the pipeline have their own way of measuring the value of water, Fulkerson said.

"You just have to go to Snake or Spring Valley to the see the seeps and springs are already drying up. That's a huge cost to the people living out there. For them, it's not just the cost of an alfalfa field. It's the cost of a heritage," he said. "There's a lot of things these damned economists can't ring up at the cash register."

Longtime Spring Valley resident Kathy Rountree couldn't agree more.

"The value of the water to us is it's our life. It's that simple," she said. "If this place dries up, we're dead."

Some believe Southern Nevada faces a similar plight.

Water authority General Manager Pat Mulroy said the ongoing drought on the Colorado River has dramatically increased the need for an alternate water source like the one the pipeline would provide.

"The decision of whether or not to build it is not exclusively an economic one," Mulroy said. "Yes, it's going to cost more money. The dynamic has changed. The cheap water, the water we could get for three nickels, is gone."

The valley gets about 90 percent of its water from the Colorado River. That supply is essentially free -- the only cost is the energy and infrastructure required to pump it from Lake Mead -- but it is also under threat by drought and mounting demand for water across the West.

Besides, Mulroy said, the water authority's new holdings in Spring Valley actually amount to a lot more than 40,000 acre-feet. When you include the other groundwater rights the authority owns there and stretch the full amount through reuse, Spring Valley could yield as much as 120,000 acre-feet, enough to supply almost a quarter of a million homes.

"That's what the real block is," Mulroy said.

And unlike the banks of water the authority has secured in Arizona and elsewhere in recent years, its new groundwater rights in Spring Valley never expire, Wimmer said. "These are long-lived, permanent assets."

That's exactly what Abby Johnson is afraid of.

The Carson City resident protested the authority's groundwater applications in Spring Valley back when they were filed in 1989. She has since bought a home in Snake Valley and serves on the board of the Great Basin Water Network, a group dedicated to fighting the pipeline.

Johnson said the project will serve to only encourage more unsustainable growth the Las Vegas Valley.

"Whether it costs $2 billion or $4 billion or $8 billion doesn't seem important to them," Johnson said of the authority. "It seems like money is no object and water is the object."

The preliminary cost estimates for the pipeline have not been revised since 2005, but authority officials concede that the final tab could rise well above $2 billion.

How high the cost might go is almost impossible to guess, Mulroy said, because the authority does not yet know how much water it will be granted or exactly where that water will be.

There is also no way to know for sure what construction materials will cost several years from now, when work begins on the pipeline.

"Until those questions are answered, we can't develop a refined estimate," Wimmer said. "Why keep throwing out numbers for people to get excited about?"

"It won't be real until we get ready to build it," Mulroy said.

Authority officials have yet to decide how to pay for the pipeline. But the authority has decided that the project is within the agency's means.

At present, the authority funds large capital projects through a mix of revenue streams. Approximately 57 percent of the money comes from connection charges paid as new homes and businesses hook up to the valley's water system.

Sales tax revenue accounts for another 28 percent of the pie. The remaining 15 percent comes from water rates and reliability surcharges paid by customers.

Mulroy acknowledged that customers could see their water rates go up as a result of the pipeline project, but she said it is way too soon to speculate on how large a hike might be required.

Whatever it is, she doesn't expect it to be anything the community can't handle.

"Of course we can afford it. It's not a matter of afford," Mulroy said. "At the end of the day, it really gets down to how the community protects itself. It's a value judgment the community has to make."