Muhammad Ali was a perfect fit for Las Vegas — as a fighter and showman — PHOTOS

When it came to entertaining boxing fans, Muhammad Ali had no peer.

That was especially true when he fought in Las Vegas. He might not have been a regular, but he was just as much the showman as any entertainer on the Strip.

The former world heavyweight champion died Friday in a Phoenix-area hospital at age 74 from respiratory issues after battling Parkinson’s disease for the better part of three decades.

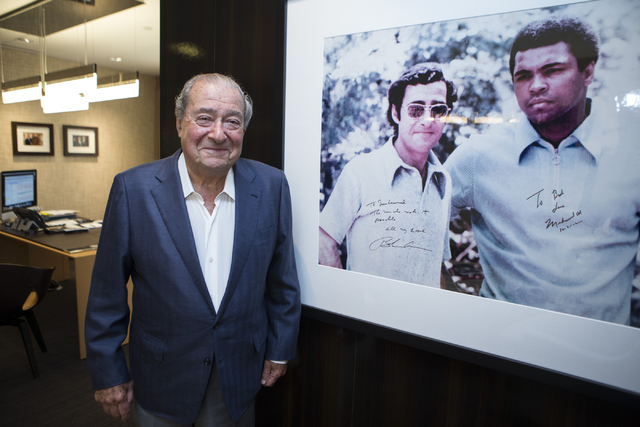

Top Rank chairman and Hall of Fame promoter Bob Arum, who got his start in the sport in 1966 because of Ali, said: “He was the most transforming figure of our time. What he did inside and outside the ring will be part of his everlasting legacy.”

Ali fought only seven times in Las Vegas. But his connection to the city transcended boxing. His daughter Rasheda Ali Walsh lives in the valley, as do two of his grandsons, Biaggio and Nico.

Biaggio, a senior running back at Bishop Gorman High School, played in front of his grandfather two years ago in Reno when Gorman won the state title. Ali sat in the stands, a blanket wrapped around him to shield him from the early December chill, as Biaggio scored two touchdowns, rushed for 137 yards and helped the Gaels defeat Reed 70-28.

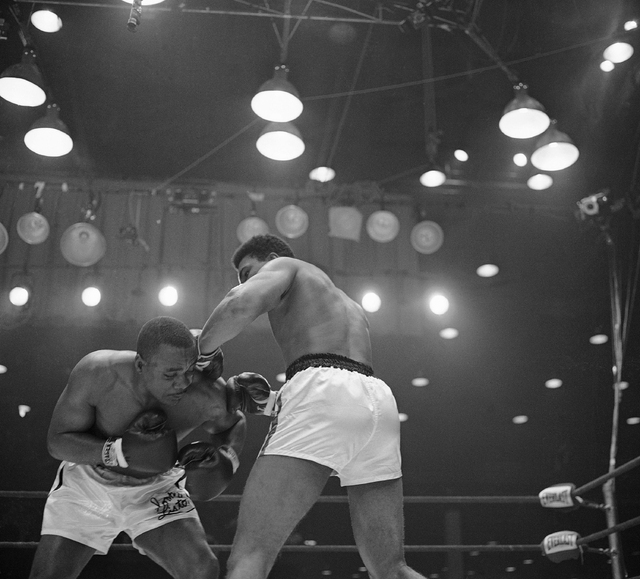

Ali went 5-2 in Las Vegas, with his first fight in 1961 when he was known as Cassius Clay. He beat Duke Sabedong at the old Las Vegas Convention Center.

“I was at that fight,” said Marc Ratner, the former executive director of the Nevada Athletic Commission. “And I became a huge Ali fan forever.”

Longtime former Review-Journal boxing writer Royce Feour was also at the Sabedong fight. He has fond memories of Ali.

“Ali won a 10-round decision,” Feour said. “At that time, I had no idea Ali would someday be the great legend he of course became.”

Ali returned to Las Vegas in 1965, and on Nov. 22, now known as Muhammad Ali after his conversion to Islam, he dominated Floyd Patterson at the Convention Center, scoring a 12th-round technical knockout to retain his title.

After returning to boxing in 1970 after he was barred from the sport for refusing induction into the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, Ali defeated Jerry Quarry in Atlanta. They had a rematch June 27, 1972, at the Convention Center, where Ali won by TKO.

Ali scored wins over Joe Bugner in 1973 and Ron Lyle in 1975, both at the Convention Center. But his luck in Las Vegas would ultimately run out.

On Feb. 15, 1978, Leon Spinks, who had just seven professional fights under his belt, won the World Boxing Council and World Boxing Association heavyweight titles from Ali when he scored a 15-round split decision at the Las Vegas Hilton. Ali won the rematch seven months later at the Louisiana Superdome to win back the WBA belt.

“When Ali lost his title to Leon Spinks, I told people at ringside that I thought Spinks won the fight but that the judges wouldn’t give him the decision because they wouldn’t vote against Ali,” Feour said. “I was wrong.”

On Oct. 2, 1980, in the outdoor arena at Caesars Palace, Ali was pounded by undefeated Larry Holmes, as Ali trainer Angelo Dundee had the fight stopped after the 10th round.

“A very sad night,” Feour said. “Ali was only a mere shadow of his former self, and the fight probably should have not been sanctioned.”

Ali was 56-5 with 37 knockouts during his Hall of Fame career, one that transcended boxing and a life that had more than its share of controversy. Arum remembers Ali as being a man of principle.

“He knew what he was doing,” Arum said in 2012 when Ali was honored at the Power of Love gala at the MGM Grand Garden. “Most people disliked him for his stances. He was a pariah to a lot of people. To some, he was a traitor. But he was willing to risk everything for what he believed.”

Las Vegas resident Gene Kilroy and Ali became friends in 1960, when Ali won a gold medal in the Rome Olympics. Kilroy was Ali’s business manager from 1968 to 1980.

“He loved people, and he judged people as people,” Kilroy said. “Ali didn’t see color. The casino owners loved him. They knew he was good for business, and there’s no doubt Ali helped desegregate Las Vegas.”

When Ali fought Patterson in 1965, segregation was still part of life in Las Vegas. But Ali stayed and trained at the Stardust instead of staying at a blacks-only establishment in west Las Vegas.

“He opened the door for others,” local talk radio host Patricia Cunningham said in 2012. “To integrate the Strip was a business decision. I’m sure by staying on the Strip, he helped immensely. It sent a signal to the other casino owners that the only color that really mattered was green.”

Feour remembers Ali training at the Stardust.

“Ali had a profound effect on the public,” he said. “I remember him training for one fight in the Stardust showroom, and the hundreds of fans there were absolutely enthralled. They leaned in on Ali’s every move and every word when he talked to the crowd.”

Arum said Ali was one of the most important figures of the 20th century.

“He’s ahead of everybody,” Arum said. “Ali’s main contribution as a person of color could have an impact on the unfolding of world events. He took a principled stand on society — race, Vietnam, religion — he stood up at a time and took a stand that wasn’t the most popular. But he changed the world.”

The Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame inducted Ali in 2015, changing its rules to allow him to be voted in.

“People asked me, ‘How can you have a Boxing Hall of Fame and not have Muhammad Ali in it?’” president and founder Rich Marotta said last year. “And you know what? They were right.

“He has meant so much to the sport. He’s such an iconic figure, both in and out of the ring. It was important that we have a place for him in the Hall of Fame. It definitely boosts our credibility.”

Kilroy said Ali and Las Vegas were two of a kind.

“He always loved Las Vegas, and Las Vegas always loved him,” Kilroy said. “They were the perfect match for each other. He loved to entertain, and Vegas is the entertainment capital of the world.”

But in the end, Ali’s ailments got the best of him. He was a frail figure the past few years, not even close to resembling the strong, indestructible figure who dominated the ring.

“Everyone loses their last fight,” Arum said.

Contact Steve Carp at scarp@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2913. Follow on Twitter: @stevecarprj

RELATED

Muhammad Ali, 'The Greatest,' dead at 74

Ali's most memorable moments in the ring