Lombardo vs. Cannizzaro: What their dueling education bills propose

Dueling education bills on the table in the Legislature propose sweeping education changes aimed to improve accountability and retention.

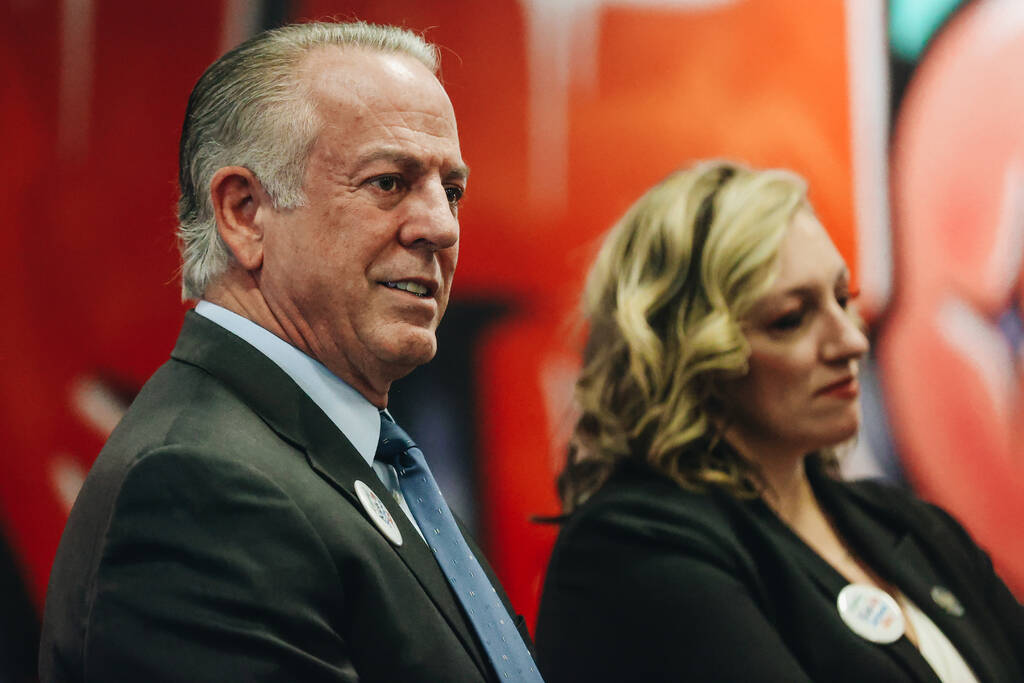

Democratic Sen. Majority Leader Nicole Cannizzaro proposed the Accountability, Transparency, and Efficiency (EDUCATE) Act, and Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo put forward the Nevada Accountability in Education Act as one of his five priority pieces of legislation.

With Democrats in the majority in the Legislature and with Lombardo’s veto power, policymakers will have to find compromise to push an education package across the finish line.

Cannizzaro’s Senate Bill 460 includes expanded Pre-K, increased accountability for public schools and publicly funded charter schools, teacher pay raises to the extent money is available and a prescribed ratio of teachers to administrators.

Lombardo’s Assembly Bill 584 includes bonuses for high-performing teachers, transportation to public charter schools, reading proficiency improvements and a statewide accountability system that puts chronically under-performing schools under the microscope.

Their proposals are part of longstanding efforts to improve the Silver State’s education system, which has ranked near the bottom for years. Lombardo campaigned to be the state’s next “education governor,” and Cannizzaro has fought for education reform since elected in 2016.

Though their bills could change as the legislative process continues, here’s a rundown of the two proposals, where they’re similar and where they differ, what they’re expected to cost and what people are saying about them.

On accountability

The biggest common interest of Lombardo and Cannizzaro is in improving accountability of school districts.

Cannizzaro’s SB 460 requires each public elementary school to prepare a plan to improve academic achievement. The plan must include a three-year strategic plan to improve achievement, with goals set for each school year. It must also include professional development requirements and remedial study for English language arts, math and science.

If a school does not meet the goals outlined in its plan, the principals at the schools are evaluated and may be removed from their position by the superintendent.

The Department of Education also has the power to remove the superintendent of a school district if it is determined that at least 30 percent of its schools are not demonstrating academic growth or proficiency.

SB 460 would also create a School District Oversight Board that would be impaneled if a complaint is filed alleging a school district is failing to comply with state requirements. If a corrective plan doesn’t address the failure, other steps will be taken, including the district being declared in a state of emergency by the governor, allowing the state to take action to fix the non-compliance.

Lombardo’s AB 584 would focus on school districts, looking at performance and governance, which includes leadership instability, financial hardship or systemic inequity. Each district would receive an annual ranking, and some could be ranked as “low performing.”

The state superintendent of public instruction will be required to place underperforming school districts on probation, and the school district would have to submit a performance improvement plan and a school board improvement plan.

If school districts fail to improve after two years, actions will be taken, including replacing the paid leadership of the school district — including the school’s superintendent — reallocating school district resources to prioritize support for low-performing schools and assuming state control over certain functions of the school district.

A “low-performing” school would be any public school in which students’ English language arts and math proficiency is at the bottom 20th percentile of statewide performance metrics, a high school where the average graduation rate is less than 60 percent for the last three school years, or elementary schools where more than 50 percent of students don’t achieve adequate proficiency in reading by grade 3.

About 53 percent of schools in Nevada currently would be designated as low-performing under those guidelines, according to Steve Canavero, Nevada’s interim superintendent of Public Instruction.

The Department of Education would provide additional support to those persistently underperforming schools, such as leadership coaching for principals and professional development for teachers.

If a school district is designated as low performing for three consecutive years, it must provide expanded achievement options for students, such as helping them attend another public school, a public charter school or a private school.

Once a school improves, oversight would be phased out.

Teachers or administrators could also be placed on probation by the district superintendent if their performance is designated as ineffective for two consecutive years, and a performance improvement plan would be required. If the teacher doesn’t meet the improvement goals, they could be dismissed or not re-hired.

Lombardo’s bill also creates the Board of the Education Service Center, a volunteer seven-member board that would provide guidance to low-performing public schools and districts.

On compensation and retention

Cannizzaro’s bill will require trustees of each large school district to reserve funds for salary increases of licensed teachers, licensed administrators and principals, to the extent money is available.

It requires the Clark County School District to establish a differential pay-scale for educator positions in Title I schools with vacancy rates of 7 percent or more for at least two years.

The bill also requires each large school district to negotiate with an employee organization, such as a teacher’s union, to develop a salary incentive program for professional growth for teachers and principals.

Her bill also creates a 17-member Commission on Recruitment and Retention in Nevada’s Department of Education.

Lombardo’s bill proposes establishing a dedicated account called the Excellence in Education Account within the State Education Fund to reward continuously high-performing teachers with bonuses, according to a summary provided by the governor’s office.

The account would be funded by surplus dollars from the Education Stabilization Account, which has approximately $845.7 million. It’ll not exceed $30 million and will pay out financial incentives of up to 10 percent of a teacher’s salary.

On charter schools

Perhaps the most polarizing difference between the two bills is how they deal with Nevada’s public charter schools — the biggest topic brought up during the bills’ public comment periods.

Cannizzaro’s bill aims to increase oversight and accountability of publicly funded charter schools.

“I want to stress that I believe that charter schools are an important part of our educational system,” Cannizzaro said during her bill’s hearing. “I do believe that when we talk about accountability, we can actually talk about accountability for all schools that are public schools or publicly funded.”

SB 460 allows school trustees in some districts to object to proposals to establish a public charter school in their district. The State Public Charter School Authority would review the objection, issue a finding and decide whether to approve the proposed charter school. A school board could appeal the ruling to the State Board of Education, which would have 10 days to respond with a decision.

If a proposed charter school is in a county of 400,000 or more, the State Public Charter School Authority must hold a public hearing to approve the proposed school.

The bill also requires two members of the nine-member State Public Charter School authority to be a parent or guardian of a student enrolled in a charter school, appointed by the governor.

And finally, Cannizzaro’s bill requires every teacher at a charter school — with some exceptions — to hold a license to teach in Nevada, increasing the current requirement that 80 percent of teachers at a charter school have a license.

Lombardo’s bill calls to ensure funding parity for charter schools and provide them with more support.

“This bill delivers on a core commitment and belief of mine: Every Nevada student deserves access to a high quality education regardless of their ZIP code or their family’s income,” Lombardo said during his bill’s hearing.

It would require school districts to provide transportation funding for students who live by low-performing schools to attend a high-ranked school, including public charter schools or state-approved private schools.

His bill also allows a city or county to sponsor a new charter school if the city or county is in a school district designated as low performing.

The cost

The estimated financial impact for both bills remains in flux as the bills change. Legislators are working with less money than anticipated, forcing them to remove provisions that could cost the state money it doesn’t have.

Cannizzaro’s bill would cost approximately $24.6 million to administer the functions of the legislation, though her office expects that number to fall with amendments. Her bill also includes about $356 million in appropriations, however $250 million of that is already included in the K-12 budget.

The cost of the governor’s bill is even less certain. Approximately $8 million would be required for administering the provisions of the bill. That number also includes the cost of contracts and professional development, according to the governor’s office. Additional costs are unknown. Because some of the provisions would not go into effect until the 2028-2029 biennium, estimated costs weren’t considered.

Contact Jessica Hill at jehill@reviewjournal.com. Follow @jess_hillyeah on X.

What are people saying?

The Clark County Education Association, Nevada Association of School Boards, the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, ACLU of Nevada and teachers testified in support of Sen. Nichole Cannizzaro's bill.

"The accountability provisions in SB 460 are necessary to ensure all stakeholders from district leadership to educators are held responsible for student outcomes," said Marie Neisess, president of CCEA, during the bill hearing.

Those opposed, however, include students and representatives from public charter schools, who testified in opposition saying it hurts charter schools.

"It will hurt charter schools and hurt students on the Opportunity Scholarships," said Colton Brown, a student at the Academy of Arts, Careers, and Technology in Reno. "Education isn't one size-fits all. For some of us the traditional education system doesn't work. That's why this bill and school choice matters so much for students."

Gov. Joe Lombardo's bill was met with wide support from public charter schools, students who attend non-traditional public schools and school choice advocates.

"Thanks to Governor Lombardo, Nevada is on its way to becoming a true school choice state giving the children the tools to thrive," said Juliette Leong, a 9-year-old homeschooled student.

Opponents of the governor's proposal included the Washoe County School District, the Nevada Association of School Superintendents and teachers with the Nevada State Education Association members, who called the bill "anti-teacher."

"Expecting schools to do more with less feels like watching someone struggle to swim and being told to shout directions at them from the shore," said Rachel Croft, a teacher in Carson City. "Assembly Bill 584 demands better outcomes without giving us the per pupil student funding that we need to achieve them."