Concrete sets path for valley water

Fed by a flotilla of barges loaded with mixing trucks, a crew of workers pumps concrete straight down into the cold, dark bed of Lake Mead.

Their target lies 350 feet beneath them, and from their floating work site two miles from shore, they expect to come within an inch of hitting it.

The massive underwater concrete pour now under way will secure the opening for a new intake pipe that will deliver drinking water to Las Vegas from the bottom of the lake.

The third intake is slated for completion in early 2014, but the so-called "marine" portion of the project is nearly finished. The continuous pour that began on Thursday represents the final piece of the job.

Casey Graham, superintendent for the underwater work, said the concrete will continue to flow day and night until the last cubic foot is placed sometime Friday morning.

"Wind hinders us pretty good, but nothing really stops us," he said.

The work starts on shore, where mixers loaded with a special blend of concrete are driven onto barges eight at a time and ferried across the water with their drums still turning.

When the barges reach the floating work platform, the concrete is dumped from the trucks onto a conveyor, carried to a pump and injected into a pipe boom that extends to the bottom of the lake.

As of Monday morning, the barges had made about 50 trips to the platform, and roughly 4,000 cubic yards of concrete had been poured. That is enough to make foundations for roughly 150 single-family homes.

It will take about 12,000 cubic yards to secure the intake structure -- basically a concrete-and-steel funnel about 100 feet tall and weighing 1,200 tons -- that was lowered to the bottom of the lake last month.

At about $800 million, the third intake is the most complicated and expensive construction job in the history of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. The agency's board approved a rate increase last week to help cover the last $360 million of the project.

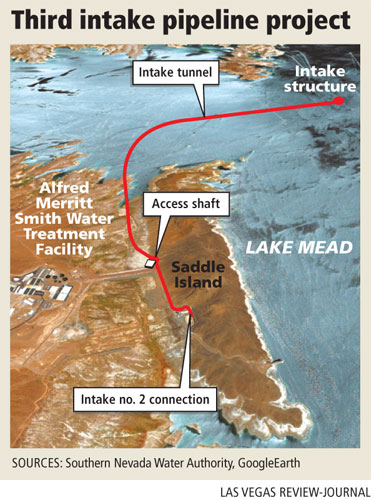

The third intake is designed to keep water flowing to Las Vegas even if Lake Mead shrinks enough to force the two existing straws to shut down.

The Las Vegas Valley depends on the lake for about 90 percent of its drinking water supply. Henderson and Boulder City draw all of their water from the Colorado River's largest reservoir.

Graham said there is one simple rule for pouring concrete to the bottom of a lake: "Keep it from coming into contact with the water."

The workers accomplish that by inserting the pipe boom into concrete that already has been poured and shooting the new stuff into the middle of the old.

Graham said it takes the mix about 30 hours to set, which gives them enough time to inch their way around the intake structure and add new layers before everything hardens.

There are no divers in the water guiding the work. The crew at the surface uses sonar, GPS sensors and a single remote-controlled submarine to "see" what's happening at the bottom of the lake.

In the pitch-black, 53-degree water, the submarine's lights illuminate the ghostly shape of the intake structure decorated with logos from the water authority, the general contractor, Vegas Tunnel Constructors, and its parent company, the Italy-based Impregilo group. Unless Lake Mead shrinks to apocalyptic levels, the decals will never again see the light of day.

Robin Rockey, who serves as the water authority's liaison to the project, said workers don't need to be able see the site because it has been studied so thoroughly.

"It's all surveyed to the minute detail so they know exactly where everything is," she said. "They have to know exactly where it all is so the TBM can hit its mark."

TBM is short for tunnel boring machine, a 24-foot-tall rock-chewing worm now digging its way beneath the bed of Lake Mead.

The $25 million excavator was specially designed and built in Germany for the third intake project.

After several early setbacks, the TBM was lowered into the ground late last year.

At last check, Rockey said, the machine had covered the first 340 feet of its roughly three-mile trip through solid rock. Two years from now, it is expected to end its journey by punching into the side of the intake structure at a precise spot plotted down to the inch.

The project has seen its share of setbacks.

A series of cave-ins 600 feet underground has left the massive tunneling job more than a year behind schedule and eaten up most of the contingency funds built into its budget.

The marine side of the project also fell behind schedule when demolition work at the bottom of the lake took longer than expected.

More than 25,000 cubic yards of material had to be blasted and removed from the lake bed to make way for the intake structure. That work was finally finished in December.

A frame was lowered into place in January, followed a few weeks later by the precast intake structure itself, which was floated out to the site and methodically sunk over the course of 56 hours, Graham said.

Then came the concrete.

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal .com or 702-383-0350.