LAS VEGAS AND NEVADA RANK LAST IN COUNTRY

When the Las Vegas Elks, headed by the late "Big Jim" Cashman, decided the city needed a minor league baseball team, hundreds of volunteers turned out to build a stadium.

That was nearly 60 years ago. Tim Cashman heard the story of the original Cashman Field many times from his father, James Cashman Jr., who died in 2005.

"My grandfather sort of led the effort and rallied the troops in the community," says Cashman, who is 48. "There was pride in being able to get things done, no questions asked."

Where has that volunteer spirit gone? According to a national report released earlier this year, Las Vegans volunteer the least among residents in 50 major cities.

Many, including Cashman, partly fault the area's rapid growth. The approximately 6,000 people who move here each month probably feel stronger ties to the towns they have left, they say, than the one in which they have just arrived.

The city's transient population alone doesn't explain its dismal rate. But there is a connection between how deeply people feel attached to a community and their willingness to volunteer.

The Corporation for National & Community Service (CNCS), a federal agency that issued the report in July, says it's hard to build civic ties when there is a large influx of new residents. Likewise, dense populations create a sense of anonymity that makes it difficult to know one's neighbors.

When community attachment is combined with other social and demographic factors -- such as commute times, education levels and the prevalence of nonprofits -- they provide a virtual blueprint for predicting how likely a city's residents are to give of their time.

High commute times mean less time to volunteer. Low education levels decrease civic involvement. And fewer nonprofits provide fewer volunteer opportunities.

Las Vegas is headed the wrong way in each of these categories.

The city also happens to be in the state with the lowest volunteer rate, for two years running, among the 50 states and Washington, D.C.

Since most Nevadans live in the Las Vegas Valley, did they drag down the state's ranking as well?

Is Las Vegas just a mean or apathetic town?

The question is worth pondering because much is at stake.

Volunteerism is a key indicator of "social capital," which the CNCS defines as "our social connectedness or social networks and the related norms of trust and reciprocity." Social capital, the agency says, is tied to quality of life, as measured by parents' involvement in schools, economic strength, crime levels and even incidences of illness.

"It isn't just something that is nice for the community. It is necessary for a community to work well," says Robert Grimm, director of CNCS' research and policy development office and lead author of the cities report.

It was no coincidence, he says, that residents of Minneapolis-St. Paul, the metro area with the highest volunteerism rate, pitched in after an interstate bridge there collapsed on Aug. 1, killing 13 people and injuring about 100.

"You didn't hear stories about how people didn't respond appropriately," Grimm says.

"They tried to rescue individuals and improve the situation as quickly as possible. People showed up and made a dramatic impact because of the social capital there."

While there are no absolutes, Grimm says, the depth of roots people have in a place influences their willingness to volunteer.

"It is one factor that makes it more likely that you might engage in your community because you are thinking of being there for the long term," he says.

"It's a different perspective if you think you will be here a year or two and then be gone. People's engagement rate may differ by how long they will be in the community, and home ownership is one way to get at that."

The report pegs Las Vegas' home ownership rate at 54.1 percent.

But that figure might actually overstate just how deeply rooted some Las Vegans feel.

Close to half of the approximately 30,000 homes listed for sale in Clark County in October were vacant. Some of those empty homes were bought by investors and never occupied.

Thus, their ties to the area could be purely financial.

Figures from the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas show that 5,196 adults moved to the area in October, down 15.4 percent from 6,142 a month earlier.

Population growth has slowed to an estimated 50,000 new residents per year. At the same time, about a third of that many people leave.

It may seem higher, but residents who have lived in the area for less than a year account for only 5.2 percent of the local population, according to the 2007 Las Vegas Perspective, a statistical research publication.

The figure jumps dramatically to 23.6 percent for residents who have stayed for one to five years.

Fewer than 29 percent have lived in the area more than 20 years.

You don't have to be a newcomer to feel the turnstile effect.

Robert Parker, a sociology professor at UNLV, says a 10-year resident he knows summed up a common sentiment: "I would be volunteering if this was my home. ... I have no sense of 'this is home.' Even my last home is more home than this, and even my future home has more of a feeling of home than what I have now."

That detachment comes at a personal cost. The only real relationships his friend says he has are with his wife and his work.

Parker has pondered the issue of volunteerism as part of urban sociology and community studies for at least 20 years. While he has no scientific proof of why Las Vegans volunteer the least, he says, he has developed some theories.

The economic emphasis on tourism comes at the expense of residents, he says, adding to a sense of disconnect they may already feel with their rapidly-changing city.

"We certainly do everything we can to make it an accommodating, clean, safe experience for these 40 million people who come here for a few days a year, but what do we do for those people who pay most of the taxes, who do most of the work and most of the consuming?" Parker asks.

"There are 2 million people here, and nobody ever talks about the residents."

Parker cuts some of them slack for not volunteering. Many have low-paying service jobs with little money or spare time, he says, sharing homes with other wage-earners to make ends meet.

At the same time, many people don't see value in pursuits other than acquiring more money and possessions.

Rapid growth is part of the volunteer equation, Parker says. Maintaining a sense of connection can be challenging even as a consumer -- imagine the longtime patron who finds his favorite haunt permanently closed, with no warning.

But Las Vegas has always been a boom town. And swelling populations didn't seem to conclusively hamper volunteerism in Phoenix; Austin, Texas; and Atlanta, which were recently identified by Forbes.com as the nation's fastest-growing cities, respectively, after Las Vegas.

Phoenix fared the worst of the three, coming in at 41st place among the 50 cities. Austin came in third; Atlanta, 38th.

These cities, all of which are older than Las Vegas, scored better on various indicators that CNCS says influence volunteerism.

What they also have in common are more varied diversions for their residents, Parker says.

"Here, the choices are casinos or not," he says. "I don't know where all of the 'nots' go."

The volunteerism rates among cities are based on three-year averages from 2004 to 2006, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In each of those years, the Census Bureau asked about 60,000 households, or 100,000 people, about the frequency, intensity and type of volunteering they did.

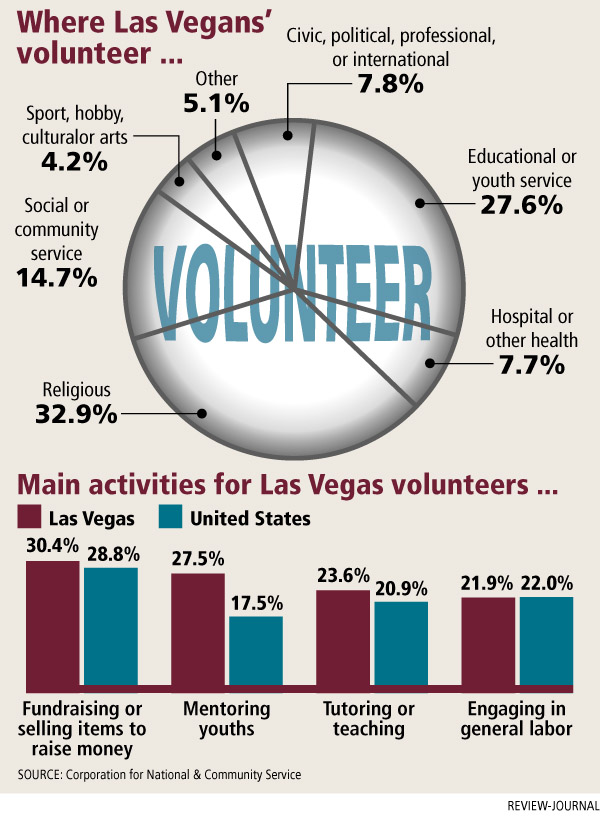

A total of 3,036 Las Vegans participated in that survey. Based upon that sample, 14.4 percent of the population actively volunteered. Applying that percentage to population figures from the two government bureaus, CNCS calculated that Las Vegas had some 188,000 volunteers who donated 26.8 million hours annually.

The average volunteer rate among the 50 cities was 28.1 percent of a population. Minneapolis-St. Paul topped the charts at 40.5 percent.

Las Vegas had the lowest volunteer rate at 14.4 percent. It also had the lowest median volunteer time, 20.5 hours per year. That means half the volunteers gave more than that amount of time and half gave less.

Not everyone agrees that Las Vegas deserves its low scores.

Cashman, "Big Jim" Cashman's grandson, says he sees no shortage of the volunteer spirit, judging from the many nonprofits with which he is involved.

But Deni Conrad, former president of the Junior League of Las Vegas, an organization of women promoting volunteerism, says she wasn't surprised.

"It pretty much is true," Conrad says.

That doesn't mean local residents are mean or don't care about their neighbors.

Conrad says they turned out in droves to help those put out of work after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. About 20,000 Las Vegans lost their jobs in just the next few months.

They also pitched in impressively after the 1980 fire at the MGM Grand, in which more than 80 people died.

But newcomers don't yet know where to go if they want to help, she says. And the 24/7 nature of Las Vegas means many shift workers simply aren't always available when they are needed.

Conrad says it was easier to find volunteers 25 years ago when she joined the nonprofit. Most members didn't hold jobs outside the home in those days.

The community, which had about 500,000 residents at the time, also was closer-knit.

"There was a core of volunteers,'' she says.

"People knew each other, people knew the issues in the community. People had a sense of community."

Nowadays, the Junior League scrambles for volunteers to staff its projects, despite the fact that its strong name recognition brings in many new members who belonged to affiliate leagues in other cities.

The organization meets that challenge by limiting the number of hands-on projects that require members to staff events at specific times. It focuses more on fundraising.

Grimm, the report's main author, says one factor affecting volunteerism sometimes minimizes the impact of another.

Take Washington, D.C. Its volunteer rate of 31.9 percent might have been lower, but its high commute time was offset by relatively high education levels and a multitude of nonprofits.

Las Vegas' home ownership rate ranked 45th among the 50 cities. Other factors dragging down its volunteer rate were its dismal graduation rates -- 43rd for high school and 49th for college -- and its paucity of nonprofits per capita, which ranked 50th. The latter figure means there are simply fewer varieties of service to attract would-be volunteers than in the other cities, Grimm says.

The agency also found "a leaky bucket," of volunteers, he says. The city's retention rate is 61.7 percent, meaning about one in three people who volunteered one year didn't do so the next.

The good news is that low volunteerism is reversible. The report noted that improvements in factors cited -- commute times to work, poverty rates, education levels, percentage of multi-unit housing, population density and the number of local nonprofit associations and groups -- could boost volunteer rates.

For example, if the average rate of high school graduates among cities rose from its current 83 percent to 87 percent, the volunteer rate could gain 4.1 percentage points.

If the share of residents with at least a four-year college degree increased by 5 percentage points to 33 percent, volunteer rates could rise by 2 percentage points.

Conversely, if the average rate of multi-unit housing jumped by 6 percentage points to 40 percent, volunteer rates could drop by about 2 percentage points. And if the average commuting time rose by only three minutes to 29 minutes, volunteer rates could decline by 2.3 percentage points.

Since the report was issued, the Volunteer Center of Southern Nevada has boosted efforts to organize projects and mobilize volunteers. About 600 people joined in six community events held across the Las Vegas Valley in late October on national Make a Difference Day.

Fran Smith, the nonprofit's executive director, says she was disappointed but not surprised by the city's rock-bottom rating.

She had an inkling, she says, when the earlier state report ranked Nevada last. The Silver State also had a poor showing in United Way's "Share of Caring" index for the decade ending in 2002.

"I still hold to the belief that it's largely the newness and just wild record-breaking growth," Smith says.

"I mean, nothing can keep up. Services can't keep up, the roads can't keep up, even the sewers and the water can't keep up. Physical infrastructure can't keep up. Why would we believe that human infrastructure can keep up?"

Contact reporter Margaret Ann Miille atmmiille@reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0401.

VOLUNTEER RATE

TOP 5 CITIES

Minneapolis 40.5%

Salt Lake City 38.4%

Austin, Texas 38.1%

Omaha, Neb. 37.8%

Seattle 36.3%

BOTTOM 5 CITIES

Riverside, Calif. 20.6%

Virginia Beach, Va. 19.3%

New York 18.7%

Miami 16.1%

Las Vegas 14.4%

SOURCE: Corporation for National & Community Service