With bodies in storage, Robert Dunn sought more victims

By the time federal agents were on his trail, Robert Dixon Dunn appeared to have hunted down another potential victim.

Prosecutors say he got away with a double murder for a decade, storing the bodies of Joaquin and Eleanor Sierra at a Las Vegas storage facility while he collected their Social Security benefits.

Just months before the government cut off those funds, Dunn moved in with Mark Joseph Taylor and Mary Pendergast, an older and frail couple in Pico Rivera, Calif.

Taylor, who suffered from severe alcoholism, died within days of meeting Dunn, the last to see him alive. On that day in August 2013, Dunn used Taylor’s credit card to buy tickets to an Elton John concert in Las Vegas.

Nobody expected Taylor to live long, and the circumstances of his death were never investigated, but his widow now wonders if Dunn sped Taylor’s demise. She last saw her husband on his bed with a bottle of Jose Cuervo by his side, while Dunn dabbled on the computer nearby.

The next morning, Taylor was on his stomach, dead on the floor with an empty glass in his hand. He was 61.

“If (Dunn) facilitated it, he only facilitated it by a couple of days,” said Pendergast, now 65. Expediting death by even a minute, however, is murder.

That left Pendergast, who suffered polio as a child and cannot walk, alone with Dunn.

“I was another one of his 55-gallon drum cat sand projects,” she said in a telephone interview. “He would have had a pretty good income with mine and the two Sierras.”

Lynda Jones, who had introduced Pendergast to Dunn, prepared a 100-page report documenting everything from the concert tickets to boots Dunn bought with either Pendergast’s or Taylor’s credit card. Dunn kept driver’s licenses in his name from California, New York, Pennsylvania and Nevada. He adopted various aliases, such as Robert William Bligh and Britt Charles Smith, using a dead boy’s Social Security number to avoid detection.

After Taylor died, Dunn started to move with Pendergast from California to Las Vegas, where he could keep watch over the storage unit, just 1½ miles from the apartment he chose for them. Later she would learn Dunn used Taylor’s credit card to pay for the storage unit where prosecutors said he kept the Sierras. Prosecutors said Dunn also paid with checks drawn against the Sierras’ own account.

Pendergast said she trusted Dunn in part because he could recite Bible verses from memory.

“He sort of calmed any feelings I might have had about him,” she said. Dunn appeared “very polite, very well-mannered. He was a gentleman. He was slick.”

Dunn would help the couple with their groceries and take them out to eat, all while stealing thousands of dollars from them, Pendergast said.

When Dunn spoke of God, Pendergast, a devout Mormon, sometimes verified his words against her Bible.

“He could spout it and talk like a person of faith, and he didn’t put one iota of credence in it, not one,” said Dunn’s older brother, Tom. “Tragic, but what a wonderful manipulation tool for him.

“That goes to the core of our spirit. When people think you connect on that level, you can accomplish a lot. And he did. Which makes it all the more damnable, as far as I’m concerned.”

Dunn’s true nature soon emerged.

Touring the Crystal Cove Apartments in the west valley, Dunn pushed Pendergast’s wheelchair into a pile of rocks, and she fell to the ground. The manager of the complex helped her up, she said, while Dunn, her supposed caretaker, did nothing.

“When we got out to Vegas, he was no longer a gentleman,” she said. “He was no longer nice. He no longer liked my dogs. He was just a real pill.”

Though Pendergast had known Dunn for only a month, the man pulled out a briefcase and showed the apartment manager 30 years of job history, saying that Pendergast had worked for him and was capable of paying rent.

“I never worked for him,” Pendergast said. “I realized then I was in trouble.”

Pendergast said Dunn threatened her on a return trip to California to see a doctor.

“I’ll kill you if you say anything,” he told her.

He also said he would kill Jones because she was “nosey” and “wouldn’t leave things alone.”

Jones called police because Dunn had a warrant out for his arrest. He had stolen from his brother, skipped court and was facing years in prison.

Dunn demanded Pendergast bail him out of jail.

“What was I going to say to him? ‘No, I’m not going to bail you out. Kill me now,’ ” she said. “I was very compliant.”

But no one came to his rescue. He even wrote a letter to his brother, begging forgiveness.

“Well, this is a real messed up situation I’ve gotten myself into,” Dunn scrawled in the two-page note. “Please take my call or better yet come see me.”

Authorities confronted Dunn, now 52, about the slaying of the Sierras while he sat in the California jail. He is scheduled to appear in a Las Vegas courtroom today. While his lawyer’s request for his release probably will be denied, Pendergast still harbors fear.

“I certainly don’t want him out,” she said. “I know how dangerous he is, how clever he is.”

She agonizes over her feelings about the death penalty.

“I decided there are some people who are too sick to be in this world,” she said. “Maybe they should go on to wherever they go and make amends for what they did.”

Dunn’s mother, Beverly, died at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center in 2005, around age 77. The official cause of death was diabetic complications from gangrene after a leg injury.

But prosecutors now say they want to know more.

Chief Deputy District Attorney David Stanton said he has asked Las Vegas police detectives to dig into medical records, including details from the coroner, and find anyone who might have known her in Las Vegas.

“As you say that, I find my head shaking,” Tom Dunn said. “It’s not a surprise, but it’s hard to even imagine he would do something that unthinkable.”

But Beverly Dunn “died long before her time,” he said, explaining that her parents lived into their 90s.

Robert Dunn had his mother cremated and sent the ashes to his brother but skipped her funeral.

Even if there is no evidence Dunn killed his mother, his treatment of her in life could be a factor in his prosecution.

In 1996, when Dunn was 33, he pleaded guilty to first-degree attempted assault and second-degree attempted assault for attacking the 66-year-old woman in an Oregon Motel 6. She suffered multiple broken ribs and a broken clavicle, Las Vegas prosecutors wrote in a notice to seek the death penalty. Her left eye, cheek, chin and neck were bruised, and her chest and stomach and upper thighs were almost completely covered in bruising.

“The likelihood of him engaging in further aggressive conduct toward his mother is high,” a psychologist wrote at the time.

Dunn spent five years in prison, but his mother stayed close. She had raised her son as a grifter, and the two conned people together as they moved around the country.

“The only way they knew to get along was to take advantage of people,” Tom Dunn said.

A few years after his release, Dunn and his mother met the Sierras in Anaheim. Prosecutors say that after a move to Reno, Dunn killed the Sierras in Las Vegas in early 2003.

Over the years, prosecutors said, Dunn stole more than $200,000 from the Sierras’ federal benefits. Their mummified remains, stuffed in garbage bins filled with cat litter and sealed with duct tape, were found a year ago at All Storage at the Lakes in the west valley.

Dunn faces two counts of murder, two counts of robbery and 11 counts of theft. Prosecutors plan to seek the death penalty.

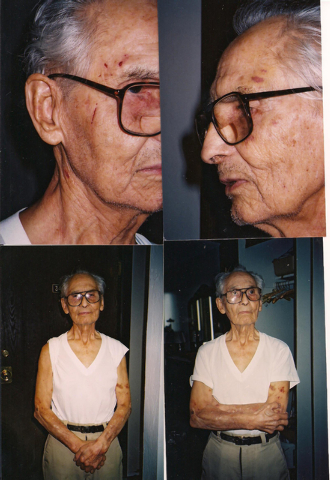

Dona Baxter, one of the closest-known relatives of the Sierras, said she worked for five months to pull her great uncle away from his wife and from Dunn.

She visited the Sierras in Reno after they had said they were robbed and needed money.

She found her uncle, a former World War II Marine, bruised on his face and arms. Baxter suspected that Eleanor Sierra abused her husband because he refused to give Dunn more money.

“Are you afraid Robert’s going to hurt you?” Baxter asked her uncle. “Yes,” he replied.

“Do you want to go to Las Vegas?”

“No.”

She brought Reno police to her uncle’s apartment, she said, but they did nothing.

“ ‘If he gets you to Las Vegas, I’m no longer an hour away (in South Lake Tahoe),’ ” she recounts telling her uncle. “ ‘I can’t just show up.’ ”

But when she went to take her uncle away in February 2003, she discovered she was three hours too late.

The trio was gone, leaving no forwarding address. Years passed before she heard anything about them.

“I was shocked to hear that they’d been found,” she said.

Contact reporter David Ferrara at dferrara@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-1039. Find him on Twitter: @randompoker