New York needs help with gambling addiction

ALBANY, N.Y. — New York state government makes more off of gambling than Nevada, New Jersey or any other state. But it spends far less than its peers to fight gambling addiction.

The state now sets aside $2.2 million annually for programs to address compulsive gambling — a tiny fraction of the $3.2 billion New York takes in every year from the state lottery, racinos and off-track betting.

“It’s not even close to what we need,” said James Maney, director of the New York Council on Problem Gambling. “Gambling is more normalized now. It’s not just the lottery or casinos. It’s fantasy football. Sports betting. Internet betting. Every form of gambling has taken off, and we haven’t done a great job of responding to it.”

New York state has long been a behemoth of legal gambling. The state now has five tribal casinos and nine racinos. The New York Lottery generates $8 billion each year — far more than any other state. When it comes to consumer spending on lottery tickets and casinos, New York is second only to California.

Four additional casinos have been authorized for upstate. A state panel reviewing 16 different proposals is expected to make its picks this fall.

“As we increase gambling opportunities, we’re going to have a lot more addiction,” said state Assemblyman Steven Cymbrowitz, a Brooklyn Democrat. “We’ve got to do more.”

The new casinos, however, will contribute an estimated $3.5 million a year toward gambling addiction programs — a significant funding increase which state officials say will make the state a leader in addressing the problem.

Estimates put the number of New Yorkers with a gambling problem between 660,000 and 1 million. It can lead to unpaid bills, bankruptcies, marital strife, job losses, legal troubles and suicide.

New York’s Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services provides treatment, trains counselors and executes public awareness and prevention campaigns. The agency also runs a telephone helpline for gamblers and their loved ones. The state also gives the Council on Problem Gaming about $1 million a year.

Pathological gambling is treated much like other addictions, with counseling, cognitive therapy, small group sessions, self-help groups such as Gamblers Anonymous and even medication. Gambling addicts sometimes struggle with alcohol, drug abuse or depression and relapse is a significant challenge. Private treatment exists, though many addicts can’t pay for it.

Effectiveness of treatment is debated. A Harvard Medical School paper concluded “although some treatment is almost certainly better than none, little is known about which treatments work best for which gamblers.”

Some of the state’s own programs appear underused. For example: the state’s gambling helpline, advertised on the back of lottery cards and in every gambling facility, received 1,224 calls for help with a gambling problem last year. The helpline in Iowa, a far smaller state, got 4,000 calls.

New York’s investment in problem gambling comes out to 11 cents per resident. Among the 39 states with publicly funded addiction programs, the average is 32 cents, according to the National Council on Problem Gambling. Pennsylvania spends about five times more per capita than New York; Iowa spends nine times more.

The law that authorized the new casinos requires them to pay $500 per slot machine or table game per year for gambling addiction programs — an arrangement estimated to generate $3.5 million. The law also required casino applicants to outline strategies to address problem gambling. State officials say the law’s requirements show the state is serious about curbing addiction.

“We are committed to problem gambling education and treatment,” Arlene Gonzalez-Sanchez, the agency’s commissioner. “We’re on the right track.”

Casino developers say they are eager to help. Many casinos train dealers and other employees about the signs of gambling addiction and operate “self-exclusion” programs that allow gamblers to ban themselves from a casino.

“Caesars wants everyone who gambles at the company’s casinos to be there for the right reasons — to simply have fun,” Caesars spokeswoman Jan Jones Blackhurst wrote last month in an explanation of her company’s stance on compulsive gambling. “Problem gambling is bad for the casino business.”

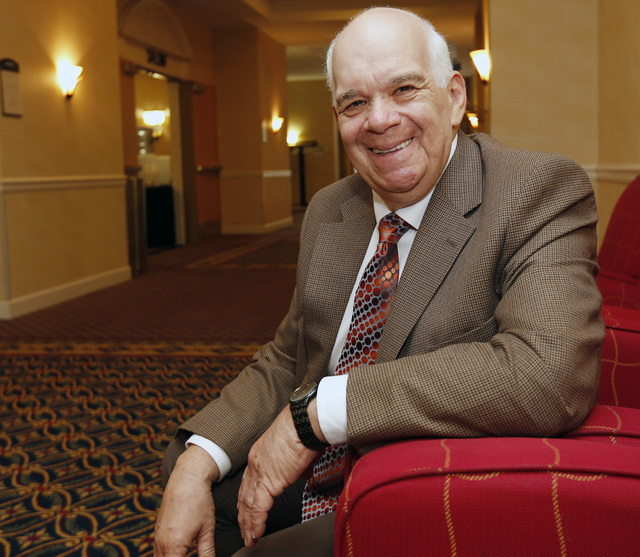

Steve Block got hooked on playing cards for money as a boy in Brooklyn and eventually moved on to placing bets with a bookie and wagering on horse races. He gambled through high school, college and 10 years of his marriage before self-help groups and counseling turned him around. Forty years later, he’s a problem gambling counselor and president of the New York Council on Problem Gaming.

Block said the state is getting more serious about addressing the problem, which he said will only increase.

“It’s a public health issue in the same way that smoking is,” he said. “Gambling is here to stay. It’s not going away. It’s expanding and we have to be ready.”