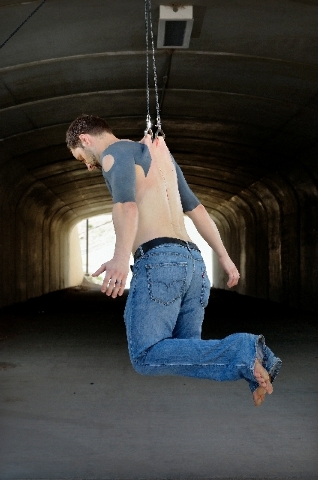

Flesh hanging lets practitioners test their limits

In March, Justine Baker allowed a friend to pierce her upper back with two giant hooks, then hang her in a tree.

She dangled there for several minutes, supported by nothing more than those pieces of metal in her skin. She took in the view of Red Rock Canyon — it was incredible, she says — and practiced a few gentle dance moves while she swayed 6 feet in the air.

The flesh on her back stretched taut but it didn’t really hurt. It was one of the most spiritual, life-affirming experiences Baker, 39, has ever had.

She plans to do it again, as soon as she has $100, the price her friends charge for a basic suspension. Like many members of the flesh suspension community, once Baker had a taste of it, she was hooked. Literally and figuratively.

At this point, you may be cringing at the thought of not only doing this yourself but seeing it done to someone. Perhaps your mind has zeroed in on a movie that depicted some form of flesh suspension and you cannot stomach the thought of all that blood and ripping flesh that is shown in film.

If so, your fears are unfounded. When done right, flesh suspension is not a gory, bloody act. See for yourselves: Baker has a YouTube video of her first flesh suspension. It has more than 300,000 hits and it is as tame as a G-rated film.

That it is gory is but one of the many misconceptions surrounding the practice of flesh suspension, says Andrew S., who owns SwingShift Sideshow with his common-law wife, Kelvita the Blade. The couple have been performing sideshow acts — including flesh suspension — in Las Vegas for several years. They also teach others how to safely suspend themselves. They helped Baker with her first time.

“One of my favorite things is to hang a first-timer,” Andrew S. says. “I like to see their expression. It’s seeing the fresh face, like they’ve just enjoyed that nice good piece of pie, that’s what’s rewarding for me.”

The reasons why people do it are as varied as one can imagine: Some do it for spiritual purposes while others do it as entertainment. Some use it as artistic expression, says Lukas Larson, owner of Dissectedart.com. He sells many of the supplies that practitioners use.

Others, such as Larson, have no interest in it artistically.

“I can appreciate it, but my motivation is to sort of understand the way the brain processes the sensory input, the pain,” Larson says. “It seems like it shouldn’t be possible to endure it, willingly.”

That’s the funny thing about flesh suspension. It looks a whole lot worse than it actually is, says plastic surgeon Julio Garcia. If it’s done safely and correctly.

While there are no flesh suspension classes or certifications for practitioners, there are certainly best practices. The body can be suspended from just about anywhere but the back has the toughest, thickest skin, the doctor says.

Some suspend by the chest, knees and legs. And the muscle is never involved.

When the skin is initially pierced, there is pain. Eventually, the nerve endings exhaust their electrical impulses and the area goes numb, Garcia says. If the hook is inserted under the skin but above the muscle, there is also very little blood.

Practitioners of flesh suspension are usually serious about safety and health; they sterilize equipment, learn CPR and ensure that suspensions are supervised, Andrew S. says.

“The question is, why are people doing this?” Garcia says. “It’s not to get people’s attention. This is really a very different beast. In general, most people I’ve read about who do this feel it as a very exhilarating experience.”

Baker’s reasoning was complex. A dancer and performer, she wanted to try flesh suspension as a means of exploring her Cherokee roots. Several indigenous tribes used the practice as a rite of passage, she says. Flesh suspension not only brings her closer to her culture but it also gives her a new way to perform, should she be unable to walk in the future.

About two years ago, she lost partial use of her legs because of a lesion in her brain that sometimes bleeds. She fears it may one day cause permanent paralysis.

“It changes how you look at the world. You ask yourself are you really living? It’s like coming out of a coma and deciding OK, this is what I’m going to do,” Baker says of her health issues. “I’m tying everything together so I can do what I love.”

Contact reporter Sonya Padgett at spadgett@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4564. Follow @StripSonya on Twitter.