Here’s why going to Mars is bad for the brain

Question: What would taking a leisurely trip to Mars do to an astronaut’s brain?

Answer: Nothing good.

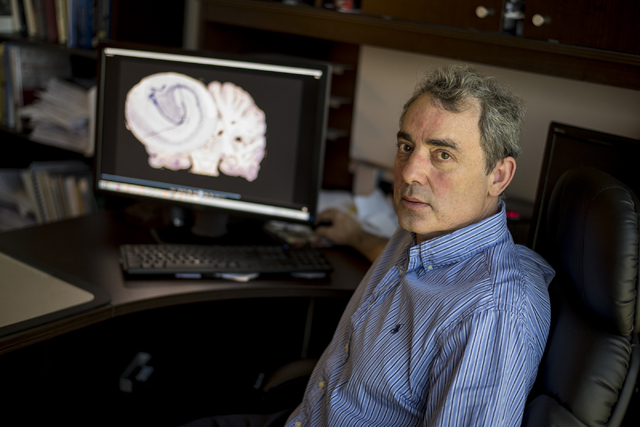

A recent study co-authored by University of Nevada, Las Vegas professor Frank Cucinotta found that the cosmic radiation astronauts would be exposed to during a trip to Mars probably would damage brain areas associated with memory and the ability to reason and carry out tasks.

All of which would be useful if, well, you’re going to Mars.

Figuring out how to mitigate the effects of cosmic radiation on Mars-bound astronauts’ brains probably isn’t an unsolvable problem. But it does underscore the health-related and medical challenges that arise as humankind seeks to continue exploring the cosmos.

Ever since the dawn of manned space exploration during the late ’50s and ’60s, researchers have known that space isn’t particularly hospitable for the human body. Beyond the obvious — no oxygen and unimaginable cold — stripping away the protection of the Earth’s atmosphere and exposing the body to a zero-gravity environment can be associated with medical issues ranging from muscle atrophy to bone loss to cataracts to cancers. It complicates even such common bodily functions as urination.

But, until recently, astronauts haven’t spent extended periods of time in deep space. Apollo moon missions typically lasted not much longer than a week at a time, and stays on the International Space Station typically are counted in months, although U.S. astronaut Scott Kelly recently began a trip to the station that is scheduled to last 342 days.

But even Kelly’s stint off-planet may be eclipsed by a trip to Mars, which could last from seven months to about two years. And that raises questions about how astronauts’ bodies might react to such long-distance space travel far from Earth.

Aiming to find out, Cucinotta, a professor in the Department of Health Physics and Diagnostic Sciences in UNLV’s School of Allied Health Sciences, co-authored a study examining one significant and vexing health hazard Mars-bound astronauts will face: cosmic radiation.

Cosmic radiation comprises highly charged, high-energy atomic nuclei from supernovae, or exploding stars. Outside of the Earth’s atmosphere, it’s a constant presence, and astronauts would be exposed to it, and its potentially harmful effects, constantly during their Mars mission.

Cucinotta is an expert in how man-made and environmental radiation affect the body. Since 2003, he has been a chief scientist with NASA’s radiation program. Last month, in the journal Science Advances, Cucinotta and other researchers reported that experiments with mice suggested “an unexpected and unique susceptibility of the central nervous system to space radiation exposure” and that exposure to cosmic radiation could adversely affect areas of the brain that would be critical to Mars astronauts’ performing their mission.

It already had been known that exposure to cosmic radiation can increase cancer risks for astronauts, Cucinotta says. Similarly, the study notes, it has been known for decades that patients who undergo radiotherapy treatment for brain malignancies can develop “progressive cognitive deficits that never resolve.”

In the study, mice were exposed to the level of cosmic radiation that astronauts would be exposed to during just a small segment of a trip to Mars. The risk of cosmic radiation to Mars astronauts, Cucinotta notes, would stem from both the length of time that the astronauts would be exposed to the radiation and the “higher rate of exposure” they’ll encounter during the trip.

“The radiation environment is different when you get away from the Earth,” Cucinotta says. That’s because the Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field deflect or block most cosmic radiation headed our way.

However, astronauts would lack that protection during their trip.

Exposure to high doses of cosmic radiation can cause massive loss of cells and necrosis in tissue, Cucinotta says. But, the recent study found, cosmic radiation exposure seems to particularly affect the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus and areas of the brain where “executive function,” or “how you integrate different processes and how you make decisions,” is controlled.

Specifically, the study found that exposure to cosmic radiation can affect an astronaut’s memory and cognition and the ability to reason, solve problems and perform tasks and can create physical changes in the brain that typically are associated with such conditions as Alzheimer’s disease.

The study is unique in that “it’s pushing the dose level down to the actual level on a Mars mission,” Cucinotta says, in contrast to studies that, for reasons of cost and practicality, expose animals to higher levels of radiation and extrapolate from that.

But still unanswered, Cucinotta says, is how data from the study might translate from mice to humans, and whether mice’s brains may be more or less sensitive to cosmic radiation than human brains.

“There would be no reason to suspect the types of molecular cell damage that occur are not very similar,” he says, “but how it affects cognition and memory might be different.”

Reducing risks to astronauts from the effect of cosmic radiation could take the form of, say, additional shielding on spacecraft. But that raises engineering and design problems, Cucinotta says.

“Our atmosphere is equivalent to 10 meters of water shielding, but a typical spacecraft has, like, 0.1 meters of shielding,” he says. “You can make some parts thick, but you could never even get to 1 meter. It would be out of the question, based on launch capabilities.”

Another option would be taking a pharmaceutical approach, using drugs to counteract the effects of radiation exposure.

“(But) then it becomes really complicated, because this isn’t the only risk for astronauts,” Cucinotta says. “There are also cancer risks and, perhaps, circulatory diseases like stroke and heart disease. And usually, when you get into (pharmaceutical) countermeasures, there can be an antagonistic effect between different effects and different tissues.”

Still another option: “You can do genetic selection for people who are resistant, but you have the same type of problems,” Cucinotta says. “If you have multiple risks, it’s really hard to find someone who’s going to be resistant to a lot of different risks.

“Also, the (astronaut) pool is narrow. We’re not thinking about selecting people from the general population. We’re talking about selecting from a few hundred people who are qualified.”

Cucinotta is optimistic that continuing research can find a solution.

“It’s the unknown,” he says. “The more you know about it, a solution will pop out.”

In the meantime, research into otherworldly cosmic radiation can help to create more effective ways of treating earthbound medical problems.

“I think there’s a big effort to use particle radiation for cancer treatment,” Cucinotta says. For example, treatment of pancreatic cancer has “an abysmal success rate — less than 10 percent. But they’re finding that using carbon (ion) beams combined with chemotherapy is improving five-year survival to about 50 percent.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280 or follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.

RELATED

Mars one-way mission candidate says venture won’t work

Meet the people who won’t be going to Mars — VIDEO

Applicants aplenty for one-way ticket to Mars